Let be a completely regular space. Let

be the Stone-Cech compactification of

. In a previous post, we show that among all compactifcations of

, the Stone-Cech compactification

is maximal with respect to a partial order

(see Theorem C2 in Two Characterizations of Stone-Cech Compactification). As a result of the maximality,

is the largest among all compactifications of

both in terms of cardinality and weight. We also establish an upper bound for the cardinality of

and an upper bound for the weight of

. As a result, we have upper bounds for cardinalities and weights for all compactifications of

. We prove the following points.

.

.

- For every compactification

of the space

,

.

- For every compactification

of the space

,

.

- For every compactification

of the space

,

.

- For every compactification

of the space

,

.

Upper Bounds for Stone-Cech Compactification

Stone-Cech Compactification is Maximal

Upper Bounds for all Compactifications

It is clear that Results 5 and 6 follow from the preceding results. The links for other posts on Stone-Cech compactification can be found toward the end of this post

___________________________________________________________________________________

Some Cardinal Functions

Let be a space. The density of

is denoted by

and is defined to be the smallest cardinality of a dense set in

. For example, if

is separable, then

. The weight of the space

is denoted by

and is defined to be the smallest cardinality of a base of the space

. For example, if

is second countable (i.e. having a countable space), then

. Both

and

are cardinal functions that are commonly used in topological discussion. Most authors require that cardinal functions only take on infinite cardinals. We also adopt this convention here. We use

to denote the cardinality of the continuum (the cardinality of the real line

).

If is a cardinal number, then

refers to the cardinal number that is the cardinallity of the set of all functions from

to

. Equivalently,

is also the cardinality of the power set of

(i.e. the set of all subsets of

). If

(the first infinite ordinal), then

is the cardinality of the continuum.

If is separable, then

(as noted above) and we have

and

. Result 5 and Result 6 imply that

is an upper bound for the cardinality of all compactifications of any separable space

and

is an upper bound of the weight of all compactifications of any separable space

.

In general, Result 5 and Result 6 indicate that the density of bounds the cardinality of any compactification of

by two exponents and the density of

bounds the weight of any compactification of

by one exponent.

Another cardinal function related to weight is that of the network weight. A collection of subsets of the space

is said to be a network for

if for each point

and for each open subset

of

with

, there is some set

with

. Note that sets in a network do not have to be open. However, any base for a topology is a network. The network weight of the space

is denoted by

and is defined to be the least cardinality of a network for

. Since any base is a network, we have

. It is also clear that

for any space

. Our interest in network and network weight is to facilitate the discussion of Lemma 2 below. It is a well known fact that in a compact space, the weight and the network weight are the same (see Result 5 in Spaces With Countable Network).

___________________________________________________________________________________

Some Basic Facts

We need the following two basic results.

-

Lemma 1

Let

-

Lemma 2

Let

Proof of Lemma 1

Let be a dense set with

. Let

be the set of all functions from

to

. Consider the map

by

. This is a one-to-one map since

whenever

and

agree on a dense set. Thus we have

. Upon doing some cardinal arithmetic, we have

. Thus Lemma 1 is established.

Proof of Lemma 2

Let be a continuous function from

onto

. Let

be a base for

such that

. Let

be the set of all

where

. Note that

is a network for

(since

is a continuous function). So we have

. Since

is compact,

(see Result 5 in Spaces With Countable Network). Thus we have

.

___________________________________________________________________________________

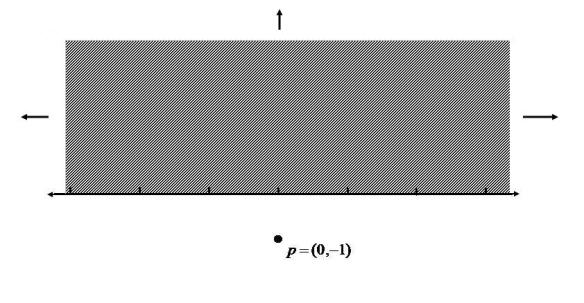

Results 1 and 2

Let be a completely regular space. Let

be the unit interval

. We show that the Stone-Cech compactification

can be regarded as a subspace of the product space

where

(the product of

many copies of

). The cardinality of

is

, thus leading to Result 1.

Let be the set of all continuous functions

. The Stone-Cech compactification

is constructed by embedding

into the product space

where each

(see Embedding Completely Regular Spaces into a Cube or A Beginning Look at Stone-Cech Compactification). Thus

is a subspace of

where

.

Note that . Thus

can be regarded as a subspace of

where

. By Lemma 1,

can be regarded as a subspace of the product space

where

.

To see Result 2, note that the weight of where

is

. Then

, as a subspace of the product space, must have weight

.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Results 3 and 4

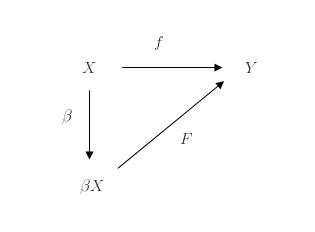

What drives Result 3 and Result 4 is the following theorem (established in Two Characterizations of Stone-Cech Compactification).

-

Theorem C2

Let

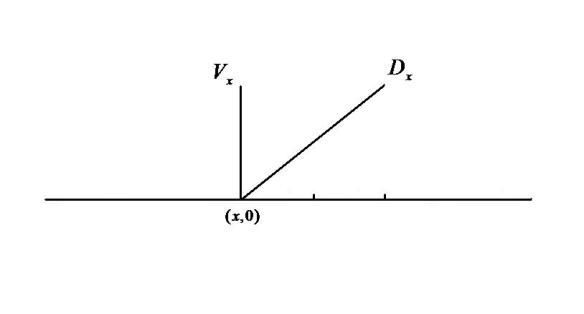

To define the partial order, for and

, both compactifications of

, we say that

if there is a continuous function

such that

. See the following figure.

Figure 1

In this post, we use to denote this partial order as well as the order for cardinal numbers. Thus we need to rely on context to distinguish this partial order from the order for cardinal numbers.

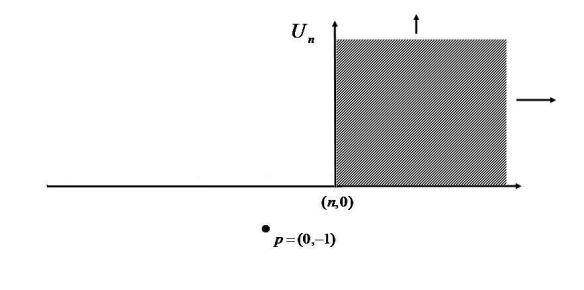

Let be a compactification of

. Theorem C2 indicates that

(partial order), which means that there is a continuous

such that

(the same point in

is mapped to itself by

). Note that

is the image of

under the function

. Thus we have

(cardinal number order). Thus Result 3 is established.

By Lemma 2, the existence of the continuous function implies that

(cardinal number order). Thus Result 4 is established.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Blog Posts on Stone-Cech Compactification

-

Post #0: Embedding Completely Regular Spaces into a Cube

Post #1: A Beginning Look at Stone-Cech Compactification

Post #2: Two Characterizations of Stone-Cech Compactification

Post #3: C*-Embedding Property and Stone-Cech Compactification

Post #4 (this post): Stone-Cech Compactification is Maximal

Post #5: Stone-Cech Compactification of the Integers – Basic Facts

Post #6: Stone-Cech Compactifications – Another Two Characterizations

___________________________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Engelking, R., General Topology, Revised and Completed edition, Heldermann Verlag, Berlin, 1989.

- Willard, S., General Topology, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1970.

___________________________________________________________________________________