The preceding post is an exercise showing that the product of countably many  -compact spaces is a Lindelof space. The result is an example of a situation where the Lindelof property is countably productive if each factor is a “nice” Lindelof space. In this case, “nice” means

-compact spaces is a Lindelof space. The result is an example of a situation where the Lindelof property is countably productive if each factor is a “nice” Lindelof space. In this case, “nice” means  -compact. This post gives several exercises surrounding the notion of

-compact. This post gives several exercises surrounding the notion of  -compactness.

-compactness.

Exercise 2.A

According to the preceding exercise, the product of countably many  -compact spaces is a Lindelof space. Give an example showing that the result cannot be extended to the product of uncountably many

-compact spaces is a Lindelof space. Give an example showing that the result cannot be extended to the product of uncountably many  -compact spaces. More specifically, give an example of a product of uncountably many

-compact spaces. More specifically, give an example of a product of uncountably many  -compact spaces such that the product space is not Lindelof.

-compact spaces such that the product space is not Lindelof.

Exercise 2.B

Any  -compact space is Lindelof. Since

-compact space is Lindelof. Since ![\mathbb{R}=\bigcup_{n=1}^\infty [-n,n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbb%7BR%7D%3D%5Cbigcup_%7Bn%3D1%7D%5E%5Cinfty+%5B-n%2Cn%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) , the real line with the usual Euclidean topology is

, the real line with the usual Euclidean topology is  -compact. This exercise is to find an example of “Lindelof does not imply

-compact. This exercise is to find an example of “Lindelof does not imply  -compact.” Find one such example among the subspaces of the real line. Note that as a subspace of the real line, the example would be a separable metric space, hence would be a Lindelof space.

-compact.” Find one such example among the subspaces of the real line. Note that as a subspace of the real line, the example would be a separable metric space, hence would be a Lindelof space.

Exercise 2.C

This exercise is also to look for an example of a space that is Lindelof and not  -compact. The example sought is a non-metric one, preferably a space whose underlying set is the real line and whose topology is finer than the Euclidean topology.

-compact. The example sought is a non-metric one, preferably a space whose underlying set is the real line and whose topology is finer than the Euclidean topology.

Exercise 2.D

Show that the product of two Lindelof spaces is a Lindelof space whenever one of the factors is a  -compact space.

-compact space.

Exercise 2.E

Prove that the product of finitely many  -compact spaces is a

-compact spaces is a  -compact space. Give an example of a space showing that the product of countably and infinitely many

-compact space. Give an example of a space showing that the product of countably and infinitely many  -compact spaces does not have to be

-compact spaces does not have to be  -compact. For example, show that

-compact. For example, show that  , the product of countably many copies of the real line, is not

, the product of countably many copies of the real line, is not  -compact.

-compact.

Comments

The Lindelof property and  -compactness are basic topological notions. The above exercises are natural questions based on these two basic notions. One immediate purpose of these exercises is that they provide further interaction with the two basic notions. More importantly, working on these exercise give exposure to mathematics that is seemingly unrelated to the two basic notions. For example, finding

-compactness are basic topological notions. The above exercises are natural questions based on these two basic notions. One immediate purpose of these exercises is that they provide further interaction with the two basic notions. More importantly, working on these exercise give exposure to mathematics that is seemingly unrelated to the two basic notions. For example, finding  -compactness on subspaces of the real line and subspaces of compact spaces naturally uses a Baire category argument, which is a deep and rich topic that finds uses in multiple areas of mathematics. For this reason, these exercises present excellent learning opportunities not only in topology but also in other useful mathematical topics.

-compactness on subspaces of the real line and subspaces of compact spaces naturally uses a Baire category argument, which is a deep and rich topic that finds uses in multiple areas of mathematics. For this reason, these exercises present excellent learning opportunities not only in topology but also in other useful mathematical topics.

If preferred, the exercises can be attacked head on. The exercises are also intended to be a guided tour. Hints are also provided below. Two sets of hints are given – Hints (blue dividers) and Further Hints (maroon dividers). The proofs of certain key facts are also given (orange dividers). Concluding remarks are given at the end of the post.

Hints for Exercise 2.A

Prove that the Lindelof property is hereditary with respect to closed subspaces. That is, if  is a Lindelof space, then every closed subspace of

is a Lindelof space, then every closed subspace of  is also Lindelof.

is also Lindelof.

Prove that if  is a Lindelof space, then every closed and discrete subset of

is a Lindelof space, then every closed and discrete subset of  is countable (every space that has this property is said to have countable extent).

is countable (every space that has this property is said to have countable extent).

Show that the product of uncountably many copies of the real line does not have countable extent. Specifically, focus on either one of the following two examples.

- Show that the product space

has a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum where

has a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum where  is cardinality of continuum. Hence

is cardinality of continuum. Hence  is not Lindelof.

is not Lindelof.

- Show that the product space

has a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality

has a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality  where

where  is the first uncountable ordinal. Hence

is the first uncountable ordinal. Hence  is not Lindelof.

is not Lindelof.

Hints for Exercise 2.B

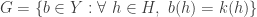

Let  be the set of all irrational numbers. Show that

be the set of all irrational numbers. Show that  as a subspace of the real line is not

as a subspace of the real line is not  -compact.

-compact.

Hints for Exercise 2.C

Let  be the real line with the topology generated by the half open and half closed intervals of the form

be the real line with the topology generated by the half open and half closed intervals of the form  . The real line with this topology is called the Sorgenfrey line. Show that

. The real line with this topology is called the Sorgenfrey line. Show that  is Lindelof and is not

is Lindelof and is not  -compact.

-compact.

Hints for Exercise 2.D

It is helpful to first prove: the product of two Lindelof space is Lindelof if one of the factors is a compact space. The Tube lemma is helpful.

Tube Lemma

Let  be a space. Let

be a space. Let  be a compact space. Suppose that

be a compact space. Suppose that  is an open subset of

is an open subset of  and suppose that

and suppose that  where

where  . Then there exists an open subset

. Then there exists an open subset  of

of  such that

such that  .

.

Hints for Exercise 2.E

Since the real line  is homeomorphic to the open interval

is homeomorphic to the open interval  ,

,  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  . Show that

. Show that  is not

is not  -compact.

-compact.

Further Hints for Exercise 2.A

The hints here focus on the example  .

.

Let ![I=[0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=I%3D%5B0%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Let

. Let  be the first infinite ordinal. For convenience, consider

be the first infinite ordinal. For convenience, consider  the set

the set  , the set of all non-negative integers. Since

, the set of all non-negative integers. Since  is a closed subset of

is a closed subset of  , any closed and discrete subset of

, any closed and discrete subset of  is a closed and discrete subset of

is a closed and discrete subset of  . The task at hand is to find a closed and discrete subset of

. The task at hand is to find a closed and discrete subset of  . To this end, we define

. To this end, we define  after setting up background information.

after setting up background information.

For each  , choose a sequence

, choose a sequence  of open intervals (in the usual topology of

of open intervals (in the usual topology of  ) such that

) such that

,

, for each

for each  (the closure is in the usual topology of

(the closure is in the usual topology of  ).

).

Note. For each  , the open intervals

, the open intervals  are of the form

are of the form  . For

. For  , the open intervals

, the open intervals  are of the form

are of the form  . For

. For  , the open intervals

, the open intervals  are of the form

are of the form ![(a,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%28a%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

For each  , define the map

, define the map  as follows:

as follows:

We are now ready to define  . For each

. For each  ,

,  is the mapping

is the mapping  defined by

defined by  for each

for each  .

.

Show the following:

- The set

has cardinality continuum.

has cardinality continuum.

- The set

is a discrete space.

is a discrete space.

- The set

is a closed subspace of

is a closed subspace of  .

.

Further Hints for Exercise 2.B

A subset  of the real line

of the real line  is nowhere dense in

is nowhere dense in  if for any nonempty open subset

if for any nonempty open subset  of

of  , there is a nonempty open subset

, there is a nonempty open subset  of

of  such that

such that  . If we replace open sets by open intervals, we have the same notion.

. If we replace open sets by open intervals, we have the same notion.

Show that the real line  with the usual Euclidean topology cannot be the union of countably many closed and nowhere dense sets.

with the usual Euclidean topology cannot be the union of countably many closed and nowhere dense sets.

Further Hints for Exercise 2.C

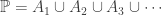

Prove that if  and

and  are

are  -compact, then the product

-compact, then the product  is

is  -compact, hence Lindelof.

-compact, hence Lindelof.

Prove that  , the Sorgenfrey line, is Lindelof while its square

, the Sorgenfrey line, is Lindelof while its square  is not Lindelof.

is not Lindelof.

Further Hints for Exercise 2.D

As suggested in the hints given earlier, prove that  is Lindelof if

is Lindelof if  is Lindelof and

is Lindelof and  is compact. As suggested, the Tube lemma is a useful tool.

is compact. As suggested, the Tube lemma is a useful tool.

Further Hints for Exercise 2.E

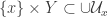

The product space  is a subspace of the product space

is a subspace of the product space ![[0,1]^\omega](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C1%5D%5E%5Comega&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Since

. Since ![[0,1]^\omega](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C1%5D%5E%5Comega&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is compact, we can fall back on a Baire category theorem argument to show why

is compact, we can fall back on a Baire category theorem argument to show why  cannot be

cannot be  -compact. To this end, we consider the notion of Baire space. A space

-compact. To this end, we consider the notion of Baire space. A space  is said to be a Baire space if for each countable family

is said to be a Baire space if for each countable family  of open and dense subsets of

of open and dense subsets of  , the intersection

, the intersection  is a dense subset of

is a dense subset of  . Prove the following results.

. Prove the following results.

Fact E.1

Let  be a compact Hausdorff space. Let

be a compact Hausdorff space. Let  be a sequence of non-empty open subsets of

be a sequence of non-empty open subsets of  such that

such that  for each

for each  . Then the intersection

. Then the intersection  is non-empty.

is non-empty.

Fact E.2

Any compact Hausdorff space is Baire space.

Fact E.3

Let  be a Baire space. Let

be a Baire space. Let  be a dense

be a dense  -subset of

-subset of  such that

such that  is a dense subset of

is a dense subset of  . Then

. Then  is not a

is not a  -compact space.

-compact space.

Since ![X=[0,1]^\omega](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=X%3D%5B0%2C1%5D%5E%5Comega&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is compact, it follows from Fact E.2 that the product space

is compact, it follows from Fact E.2 that the product space ![X=[0,1]^\omega](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=X%3D%5B0%2C1%5D%5E%5Comega&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a Baire space.

is a Baire space.

Fact E.4

Let ![X=[0,1]^\omega](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=X%3D%5B0%2C1%5D%5E%5Comega&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and

and  . The product space

. The product space  is a dense

is a dense  -subset of

-subset of ![X=[0,1]^\omega](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=X%3D%5B0%2C1%5D%5E%5Comega&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Furthermore,

. Furthermore,  is a dense subset of

is a dense subset of  .

.

It follows from the above facts that the product space  cannot be a

cannot be a  -compact space.

-compact space.

Proofs of Key Steps for Exercise 2.A

The proof here focuses on the example  .

.

To see that  has the same cardinality as that of

has the same cardinality as that of  , show that

, show that  for

for  . This follows from the definition of the mapping

. This follows from the definition of the mapping  .

.

To see that  is discrete, for each

is discrete, for each  , consider the open set

, consider the open set  . Note that

. Note that  . Further note that

. Further note that  for all

for all  .

.

To see that  is a closed subset of

is a closed subset of  , let

, let  such that

such that  . Consider two cases.

. Consider two cases.

Case 1.  for all

for all  .

.

Note that  is an open cover of

is an open cover of  (in the usual topology). There exists a finite

(in the usual topology). There exists a finite  such that

such that  is a cover of

is a cover of  . Consider the open set

. Consider the open set  . Define the set

. Define the set  as follows:

as follows:

The set  can be further described as follows:

can be further described as follows:

The last step is  because

because  is a cover of

is a cover of  . The fact that

. The fact that  means that

means that  is an open subset of

is an open subset of  containing the point

containing the point  such that

such that  contains no point of

contains no point of  .

.

Case 2.  for some

for some  .

.

Since  ,

,  for all

for all  . In particular,

. In particular,  . This means that

. This means that  for some

for some  . Define the open set

. Define the open set  as follows:

as follows:

Clearly  . Observe that

. Observe that  since

since  . For each

. For each  ,

,  since

since  . Thus

. Thus  is an open set containing

is an open set containing  such that

such that  .

.

Both cases show that  is a closed subset of

is a closed subset of  .

.

Proofs of Key Steps for Exercise 2.B

Suppose that  , the set of all irrational numbers, is

, the set of all irrational numbers, is  -compact. That is,

-compact. That is,  where each

where each  is a compact space as a subspace of

is a compact space as a subspace of  . Any compact subspace of

. Any compact subspace of  is also a compact subspace of

is also a compact subspace of  . As a result, each

. As a result, each  is a closed subset of

is a closed subset of  . Furthermore, prove the following:

. Furthermore, prove the following:

Each  is a nowhere dense subset of

is a nowhere dense subset of  .

.

Each singleton set  where

where  is any rational number is also a closed and nowhere dense subset of

is any rational number is also a closed and nowhere dense subset of  . This means that the real line is the union of countably many closed and nowhere dense subsets, contracting the hints given earlier. Thus

. This means that the real line is the union of countably many closed and nowhere dense subsets, contracting the hints given earlier. Thus  cannot be

cannot be  -compact.

-compact.

Proofs of Key Steps for Exercise 2.C

The Sorgenfrey line  is a Lindelof space whose square

is a Lindelof space whose square  is not normal. This is a famous example of a Lindelof space whose square is not Lindelof (not even normal). For reference, a proof is found here. An alternative proof of the non-normality of

is not normal. This is a famous example of a Lindelof space whose square is not Lindelof (not even normal). For reference, a proof is found here. An alternative proof of the non-normality of  uses the Baire category theorem and is found here.

uses the Baire category theorem and is found here.

If the Sorgenfrey line is  -compact, then

-compact, then  would be

would be  -compact and hence Lindelof. Thus

-compact and hence Lindelof. Thus  cannot be

cannot be  -compact.

-compact.

Proofs of Key Steps for Exercise 2.D

Suppose that  is Lindelof and that

is Lindelof and that  is compact. Let

is compact. Let  be an open cover of

be an open cover of  . For each

. For each  , let

, let  be finite such that

be finite such that  is a cover of

is a cover of  . Putting it another way,

. Putting it another way,  . By the Tube lemma, for each

. By the Tube lemma, for each  , there is an open

, there is an open  such that

such that  . Since

. Since  is Lindelof, there exists a countable set

is Lindelof, there exists a countable set  such that

such that  is a cover of

is a cover of  . Then

. Then  is a countable subcover of

is a countable subcover of  . This completes the proof that

. This completes the proof that  is Lindelof when

is Lindelof when  is Lindelof and

is Lindelof and  is compact.

is compact.

To complete the exercise, observe that if  is Lindelof and

is Lindelof and  is

is  -compact, then

-compact, then  is the union of countably many Lindelof subspaces.

is the union of countably many Lindelof subspaces.

Proofs of Key Steps for Exercise 2.E

Proof of Fact E.1

Let  be a compact Hausdorff space. Let

be a compact Hausdorff space. Let  be a sequence of non-empty open subsets of

be a sequence of non-empty open subsets of  such that $latex

such that $latex  for each

for each  . Show that the intersection

. Show that the intersection  is non-empty.

is non-empty.

Suppose that  . Choose

. Choose  . There must exist some

. There must exist some  such that

such that  . Choose

. Choose  . There must exist some

. There must exist some  such that

such that  . Continue in this manner we can choose inductively an infinite set

. Continue in this manner we can choose inductively an infinite set  such that

such that  for

for  . Since

. Since  is compact, the infinite set

is compact, the infinite set  has a limit point

has a limit point  . This means that every open set containing

. This means that every open set containing  contains some

contains some  (in fact for infinitely many

(in fact for infinitely many  ). The point

). The point  cannot be in the intersection

cannot be in the intersection  . Thus for some

. Thus for some  ,

,  . Thus

. Thus  . We can choose an open set

. We can choose an open set  such that

such that  and

and  . However,

. However,  must contain some point

must contain some point  where

where  . This is a contradiction since

. This is a contradiction since  for all

for all  . Thus Fact E.1 is established.

. Thus Fact E.1 is established.

Proof of Fact E.2

Let  be a compact space. Let

be a compact space. Let  be open subsets of

be open subsets of  such that each

such that each  is also a dense subset of

is also a dense subset of  . Let

. Let  a non-empty open subset of

a non-empty open subset of  . We wish to show that

. We wish to show that  contains a point that belongs to each

contains a point that belongs to each  . Since

. Since  is dense in

is dense in  ,

,  is non-empty. Since

is non-empty. Since  is dense in

is dense in  , choose non-empty open

, choose non-empty open  such that

such that  and

and  . Since

. Since  is dense in

is dense in  , choose non-empty open

, choose non-empty open  such that

such that  and

and  . Continue inductively in this manner and we have a sequence of open sets

. Continue inductively in this manner and we have a sequence of open sets  just like in Fact E.1. Then the intersection of the open sets

just like in Fact E.1. Then the intersection of the open sets  is non-empty. Points in the intersection are in

is non-empty. Points in the intersection are in  and in all the

and in all the  . This completes the proof of Fact E.2.

. This completes the proof of Fact E.2.

Proof of Fact E.3

Let  be a Baire space. Let

be a Baire space. Let  be a dense

be a dense  -subset of

-subset of  such that

such that  is a dense subset of

is a dense subset of  . Show that

. Show that  is not a

is not a  -compact space.

-compact space.

Suppose  is

is  -compact. Let

-compact. Let  where each

where each  is compact. Each

is compact. Each  is obviously a closed subset of

is obviously a closed subset of  . We claim that each

. We claim that each  is a closed nowhere dense subset of

is a closed nowhere dense subset of  . To see this, let

. To see this, let  be a non-empty open subset of

be a non-empty open subset of  . Since

. Since  is dense in

is dense in  ,

,  contains a point

contains a point  where

where  . Since

. Since  , there exists a non-empty open

, there exists a non-empty open  such that

such that  . This shows that each

. This shows that each  is a nowhere dense subset of

is a nowhere dense subset of  .

.

Since  is a dense

is a dense  -subset of

-subset of  ,

,  where each

where each  is an open and dense subset of

is an open and dense subset of  . Then each

. Then each  is a closed nowhere dense subset of

is a closed nowhere dense subset of  . This means that

. This means that  is the union of countably many closed and nowhere dense subsets of

is the union of countably many closed and nowhere dense subsets of  . More specifically, we have the following.

. More specifically, we have the following.

(1)………

Statement (1) contradicts the fact that  is a Baire space. Note that all

is a Baire space. Note that all  and

and  are open and dense subsets of

are open and dense subsets of  . Further note that the intersection of all these countably many open and dense subsets of

. Further note that the intersection of all these countably many open and dense subsets of  is empty according to (1). Thus

is empty according to (1). Thus  cannot not a

cannot not a  -compact space.

-compact space.

Proof of Fact E.4

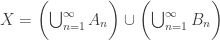

The space ![X=[0,1]^\omega](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=X%3D%5B0%2C1%5D%5E%5Comega&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is compact since it is a product of compact spaces. To see that

is compact since it is a product of compact spaces. To see that  is a dense

is a dense  -subset of

-subset of  , note that

, note that  where for each integer

where for each integer

(2)………![U_n=(0,1) \times \cdots \times (0,1) \times [0,1] \times [0,1] \times \cdots](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=U_n%3D%280%2C1%29+%5Ctimes+%5Ccdots+%5Ctimes+%280%2C1%29+%5Ctimes+%5B0%2C1%5D+%5Ctimes+%5B0%2C1%5D+%5Ctimes+%5Ccdots&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002)

Note that the first  factors of

factors of  are the open interval

are the open interval  and the remaining factors are the closed interval

and the remaining factors are the closed interval ![[0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . It is also clear that

. It is also clear that  is a dense subset of

is a dense subset of  . This completes the proof of Fact E.4.

. This completes the proof of Fact E.4.

Concluding Remarks

Exercise 2.A

The exercise is to show that the product of uncountably many  -compact spaces does not need to be Lindelof. The approach suggested in the hints is to show that

-compact spaces does not need to be Lindelof. The approach suggested in the hints is to show that  has uncountable extent where

has uncountable extent where  is continuum. Having uncountable extent (i.e. having an uncountable subset that is both closed and discrete) implies the space is not Lindelof. The uncountable extent of the product space

is continuum. Having uncountable extent (i.e. having an uncountable subset that is both closed and discrete) implies the space is not Lindelof. The uncountable extent of the product space  is discussed in this post.

is discussed in this post.

For  and

and  , there is another way to show non-Lindelof. For example, both product spaces are not normal. As a result, both product spaces cannot be Lindelof. Note that every regular Lindelof space is normal. Both product spaces contain the product

, there is another way to show non-Lindelof. For example, both product spaces are not normal. As a result, both product spaces cannot be Lindelof. Note that every regular Lindelof space is normal. Both product spaces contain the product  as a closed subspace. The non-normality of

as a closed subspace. The non-normality of  is discussed here.

is discussed here.

Exercise 2.B

The hints given above is to show that the set of all irrational numbers,  , is not

, is not  -compact (as a subspace of the real line). The same argument showing that

-compact (as a subspace of the real line). The same argument showing that  is not

is not  -compact can be generalized. Note that the complement of

-compact can be generalized. Note that the complement of  is

is  , the set of all rational numbers (a countable set). In this case,

, the set of all rational numbers (a countable set). In this case,  is a dense subset of the real line and is the union of countably many singleton sets. Each singleton set is a closed and nowhere dense subset of the real line. In general, we can let

is a dense subset of the real line and is the union of countably many singleton sets. Each singleton set is a closed and nowhere dense subset of the real line. In general, we can let  , the complement of a set

, the complement of a set  , be dense in the real line and be the union of countably many closed nowhere dense subsets of the real line (not necessarily singleton sets). The same argument will show that

, be dense in the real line and be the union of countably many closed nowhere dense subsets of the real line (not necessarily singleton sets). The same argument will show that  cannot be a

cannot be a  -compact space. This argument is captured in Fact E.3 in Exercise 2.E. Thus both Exercise 2.B and Exercise 2.E use a Baire category argument.

-compact space. This argument is captured in Fact E.3 in Exercise 2.E. Thus both Exercise 2.B and Exercise 2.E use a Baire category argument.

Exercise 2.E

Like Exercise 2.B, this exercise is also to show a certain space is not  -compact. In this case, the suggested space is

-compact. In this case, the suggested space is  , the product of countably many copies of the real line. The hints given use a Baire category argument, as outlined in Fact E.1 through Fact E.4. The product space

, the product of countably many copies of the real line. The hints given use a Baire category argument, as outlined in Fact E.1 through Fact E.4. The product space  is embedded in the compact space

is embedded in the compact space ![[0,1]^{\omega}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C1%5D%5E%7B%5Comega%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) , which is a Baire space. As mentioned earlier, Fact E.3 is essentially the same argument used for Exercise 2.B.

, which is a Baire space. As mentioned earlier, Fact E.3 is essentially the same argument used for Exercise 2.B.

Using the same Baire category argument, it can be shown that  , the product of countably many copies of the countably infinite discrete space, is not

, the product of countably many copies of the countably infinite discrete space, is not  -compact. The space

-compact. The space  of the non-negative integers, as a subspace of the real line, is certainly

of the non-negative integers, as a subspace of the real line, is certainly  -compact. Using the same Baire category argument, we can see that the product of countably many copies of this discrete space is not

-compact. Using the same Baire category argument, we can see that the product of countably many copies of this discrete space is not  -compact. With the product space

-compact. With the product space  , there is a connection with Exercise 2.B. The product

, there is a connection with Exercise 2.B. The product  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  . The idea of the homeomorphism is discussed here. Thus the non-

. The idea of the homeomorphism is discussed here. Thus the non- -compactness of

-compactness of  can be achieved by mapping it to the irrationals. Of course, the same Baire category argument runs through both exercises.

can be achieved by mapping it to the irrationals. Of course, the same Baire category argument runs through both exercises.

Exercise 2.C

Even the non- -compactness of the Sorgenfrey line

-compactness of the Sorgenfrey line  can be achieved by a Baire category argument. The non-normality of the Sorgenfrey plane

can be achieved by a Baire category argument. The non-normality of the Sorgenfrey plane  can be achieved by Jones’ lemma argument or by the fact that

can be achieved by Jones’ lemma argument or by the fact that  is not a first category set. Links to both arguments are given in the Proof section above.

is not a first category set. Links to both arguments are given in the Proof section above.

See here for another introduction to the Baire category theorem.

The Tube lemma is discussed here.

Dan Ma topology

Daniel Ma topology

Dan Ma math

Daniel Ma mathematics

2019 – Dan Ma

2019 – Dan Ma

be a mapping from a topological space

onto a topological space

. If

is a perfect map and

is a Lindelof space, then so is

. If

is a closed map and

is a paracompact space, then so is

. In other words, the pre-image of a Lindelof space under a perfect map is always a Lindelof space. Likewise, the pre-image of a paracompact space under a closed map is always a paracompact space. After proving these two facts, we show that for any compact space

, the product

is Lindelof (paracompact) for any Lindelof (paracompact) space

. All spaces under consideration are Hausdorff.

if the following holds: for any mapping

belonging to

, if

has the property, then so does

. In contrast, a topological property is an invariance of a class of mappings

if for any mapping

belonging to

, if

has the property, then so does

.

, where

, is a closed map if for any closed subset

of

,

is closed in

. A mapping

, where

, is a perfect map if

is a closed map and that the point inverse

is compact for each

.

be a closed map with

. Let

be an open subset of

. Define

. Then the set

is open in

and that

.

be a perfect map with

. Suppose

is Lindelof. Let

be an open cover of

. Without loss of generality, we can assume that

is closed under finite unions. For each

, define

. By Lemma 3, each

is an open subset of

. We claim that

is an open cover of

. To this end, let

. Since

is a perfect map, the point inverse

is compact. As a result, we can find a finite

such that

. Since

is closed under finite unions,

. It follows that

. Since

is Lindelof, there exists a countable

such that

. For each

,

for some

. We claim that

is a cover of

. To this end, let

. Then for some

,

. This implies that

. Thus, the open cover

has a countable subcover. This concludes the proof of Theorem 1.

be a perfect map with

. Suppose

is paracompact. Let

be an open cover of

. For each

, define

as in Lemma 3. By Lemma 3, each

is an open subset of

. Let

. As shown in the proof of Theorem 1,

is an open cover of

. Since

is paracompact, there exists a locally finite open refinement

of

. Let

.

. (1) It is an open cover of

. (2) It is a locally finite collection in

. (3) It is a refinement of

. To see (1), note that

is an open cover of

. As a result,

is an open cover of

. To see (2), let

. We find an open

such that

and such that

intersects only finitely many elements of

. Since

is locally finite in

, there exists an open

such that

and such that

intersects only finitely many elements of

, say,

. Let

. Clearly,

. It can be verified that the only elements of

having non-empty intersections with

are

,

,

. To see (3), let

where

. Then

for some

and some

. We claim that

. Let

. Then

. This implies that

. It follows that

is a locally finite open refinement of the open cover

. This completes the proof of Theorem 2.

is productively paramcompact if

is paracompact for every paracompact space

. The definition for productively Lindelof can be stated in a similar way. For some reason, the term “productively paracompact” is not used in the literature but is a topic that had been extensively studied. It is also a topic found in this site. The following four classes of spaces are productively paracompact (see here and here).

-compact spaces

-locally compact spaces

any compact space. Then

is Lindelof for every Lindelof space

.

any compact space. Then

is paracompact for every paracompact space

.

is compact. Then the projection map from

onto

is a closed map. The paracompactness of

follows whenever

is paracompact. The projection map is also perfect since the point inverses are compact due to the compactness of the factor

. Then the Lindelofness of

follows whenever

is Lindelof.

2023 – Dan Ma