Let  be the first uncountable ordinal. The topology on

be the first uncountable ordinal. The topology on  we are interested in is the ordered topology, the topology induced by the well ordering. The space

we are interested in is the ordered topology, the topology induced by the well ordering. The space  is also called the space of all countable ordinals since it consists of all ordinals that are countable in cardinality. It is a handy example of a countably compact space that is not compact. In this post, we consider normality in the powers of

is also called the space of all countable ordinals since it consists of all ordinals that are countable in cardinality. It is a handy example of a countably compact space that is not compact. In this post, we consider normality in the powers of  . We also make comments on normality in the powers of a countably compact non-compact space.

. We also make comments on normality in the powers of a countably compact non-compact space.

Let  be the first infinite ordinal. It is well known that

be the first infinite ordinal. It is well known that  , the product space of

, the product space of  many copies of

many copies of  , is not normal (a proof can be found in this earlier post). This means that any product space

, is not normal (a proof can be found in this earlier post). This means that any product space  , with uncountably many factors, is not normal as long as each factor

, with uncountably many factors, is not normal as long as each factor  contains a countable discrete space as a closed subspace. Thus in order to discuss normality in the product space

contains a countable discrete space as a closed subspace. Thus in order to discuss normality in the product space  , the interesting case is when each factor is infinite but contains no countable closed discrete subspace (i.e. no closed copies of

, the interesting case is when each factor is infinite but contains no countable closed discrete subspace (i.e. no closed copies of  ). In other words, the interesting case is that each factor

). In other words, the interesting case is that each factor  is a countably compact space that is not compact (see this earlier post for a discussion of countably compactness). In particular, we would like to discuss normality in

is a countably compact space that is not compact (see this earlier post for a discussion of countably compactness). In particular, we would like to discuss normality in  where

where  is a countably non-compact space. In this post we start with the space

is a countably non-compact space. In this post we start with the space  of the countable ordinals. We examine

of the countable ordinals. We examine  power

power  as well as the countable power

as well as the countable power  . The former is not normal while the latter is normal. The proof that

. The former is not normal while the latter is normal. The proof that  is normal is an application of the normality of

is normal is an application of the normality of  -product of the real line.

-product of the real line.

____________________________________________________________________

The uncountable product

Theorem 1

The product space  is not normal.

is not normal.

Theorem 1 follows from Theorem 2 below. For any space  , a collection

, a collection  of subsets of

of subsets of  is said to have the finite intersection property if for any finite

is said to have the finite intersection property if for any finite  , the intersection

, the intersection  . Such a collection

. Such a collection  is called an f.i.p collection for short. It is well known that a space

is called an f.i.p collection for short. It is well known that a space  is compact if and only collection

is compact if and only collection  of closed subsets of

of closed subsets of  satisfying the finite intersection property has non-empty intersection (see Theorem 1 in this earlier post). Thus any non-compact space has an f.i.p. collection of closed sets that have empty intersection.

satisfying the finite intersection property has non-empty intersection (see Theorem 1 in this earlier post). Thus any non-compact space has an f.i.p. collection of closed sets that have empty intersection.

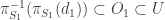

In the space  , there is an f.i.p. collection of cardinality

, there is an f.i.p. collection of cardinality  using its linear order. For each

using its linear order. For each  , let

, let  . Let

. Let  . It is a collection of closed subsets of

. It is a collection of closed subsets of  . It is an f.i.p. collection and has empty intersection. It turns out that for any countably compact space

. It is an f.i.p. collection and has empty intersection. It turns out that for any countably compact space  with an f.i.p. collection of cardinality

with an f.i.p. collection of cardinality  that has empty intersection, the product space

that has empty intersection, the product space  is not normal.

is not normal.

Theorem 2

Let  be a countably compact space. Suppose that there exists a collection

be a countably compact space. Suppose that there exists a collection  of closed subsets of

of closed subsets of  such that

such that  has the finite intersection property and that

has the finite intersection property and that  has empty intersection. Then the product space

has empty intersection. Then the product space  is not normal.

is not normal.

Proof of Theorem 2

Let’s set up some notations on product space that will make the argument easier to follow. By a standard basic open set in the product space  , we mean a set of the form

, we mean a set of the form  such that each

such that each  is an open subset of

is an open subset of  and that

and that  for all but finitely many

for all but finitely many  . Given a standard basic open set

. Given a standard basic open set  , the notation

, the notation  refers to the finite set of

refers to the finite set of  for which

for which  . For any set

. For any set  , the notation

, the notation  refers to the projection map from

refers to the projection map from  to the subproduct

to the subproduct  . Each element

. Each element  can be considered a function

can be considered a function  . By

. By  , we mean

, we mean  .

.

For each  , let

, let  be the constant function whose constant value is

be the constant function whose constant value is  . Consider the following subspaces of

. Consider the following subspaces of  .

.

Both  and

and  are closed subsets of the product space

are closed subsets of the product space  . Because the collection

. Because the collection  has empty intersection,

has empty intersection,  . We show that

. We show that  and

and  cannot be separated by disjoint open sets. To this end, let

cannot be separated by disjoint open sets. To this end, let  and

and  be open subsets of

be open subsets of  such that

such that  and

and  .

.

Let  . Choose a standard basic open set

. Choose a standard basic open set  such that

such that  . Let

. Let  . Since

. Since  is the support of

is the support of  , it follows that

, it follows that  . Since

. Since  has the finite intersection property, there exists

has the finite intersection property, there exists  .

.

Define  such that

such that  for all

for all  and

and  for all

for all  . Choose a standard basic open set

. Choose a standard basic open set  such that

such that  . Let

. Let  . It is possible to ensure that

. It is possible to ensure that  by making more factors of

by making more factors of  different from

different from  . We have

. We have  . Since

. Since  has the finite intersection property, there exists

has the finite intersection property, there exists  .

.

Now choose a point  such that

such that  for all

for all  and

and  for all

for all  . Continue on with this inductive process. When the inductive process is completed, we have the following sequences:

. Continue on with this inductive process. When the inductive process is completed, we have the following sequences:

- a sequence

of point of

of point of  ,

,

- a sequence

of finite subsets of

of finite subsets of  ,

,

- a sequence

of points of

of points of

such that for all  ,

,  for all

for all  and

and  . Let

. Let  . Either

. Either  is finite or

is finite or  is infinite. Let’s examine the two cases.

is infinite. Let’s examine the two cases.

Case 1

Suppose that  is infinite. Since

is infinite. Since  is countably compact,

is countably compact,  has a limit point

has a limit point  . That means that every open set containing

. That means that every open set containing  contains some

contains some  . For each

. For each  , define

, define  such that

such that

From the induction step, we have  for all

for all  . Let

. Let  , the constant function whose constant value is

, the constant function whose constant value is  . It follows that

. It follows that  is a limit of

is a limit of  . This means that

. This means that  . Since

. Since  ,

,  .

.

Case 2

Suppose that  is finite. Then there is some

is finite. Then there is some  such that

such that  for all

for all  . For each

. For each  , define

, define  such that

such that

As in Case 1, we have  for all

for all  . Let

. Let  , the constant function whose constant value is

, the constant function whose constant value is  . It follows that

. It follows that  for all

for all  . Thus

. Thus  .

.

Both cases show that  . This completes the proof the product space

. This completes the proof the product space  is not normal.

is not normal.

____________________________________________________________________

The countable product

Theorem 3

The product space  is normal.

is normal.

Proof of Theorem 3

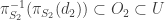

The proof here actually proves more than normality. It shows that  is collectionwise normal, which is stronger than normality. The proof makes use of the

is collectionwise normal, which is stronger than normality. The proof makes use of the  -product of

-product of  many copies of

many copies of  , which is the following subspace of the product space

, which is the following subspace of the product space  .

.

It is well known that  is collectionwise normal (see this earlier post). We show that

is collectionwise normal (see this earlier post). We show that  is a closed subspace of

is a closed subspace of  where

where  . Thus

. Thus  is collectionwise normal. This is established in the following claims.

is collectionwise normal. This is established in the following claims.

Claim 1

We show that the space  is embedded as a closed subspace of

is embedded as a closed subspace of  .

.

For each  , define

, define  such that

such that  for all

for all  and

and  for all

for all  . Let

. Let  . We show that

. We show that  is a closed subset of

is a closed subset of  and

and  is homeomorphic to

is homeomorphic to  according to the mapping

according to the mapping  .

.

First, we show  is closed by showing that

is closed by showing that  is open. Let

is open. Let  . We show that there is an open set containing

. We show that there is an open set containing  that contains no points of

that contains no points of  .

.

Suppose that for some  ,

,  . Consider the open set

. Consider the open set  where

where  except that

except that  . Then

. Then  and

and  .

.

So we can assume that for all  ,

,  . There must be some

. There must be some  such that

such that  . Otherwise,

. Otherwise,  . Since

. Since  , there must be some

, there must be some  such that

such that  . Now choose the open interval

. Now choose the open interval  and the open interval

and the open interval  . Consider the open set

. Consider the open set  such that

such that  except for

except for  and

and  . Then

. Then  and

and  . We have just established that

. We have just established that  is closed in

is closed in  .

.

Consider the mapping  . Based on how it is defined, it is straightforward to show that it is a homeomorphism between

. Based on how it is defined, it is straightforward to show that it is a homeomorphism between  and

and  .

.

Claim 2

The  -product

-product  has the interesting property it is homeomorphic to its countable power, i.e.

has the interesting property it is homeomorphic to its countable power, i.e.

.

.

Because each element of  is nonzero only at countably many coordinates, concatenating countably many elements of

is nonzero only at countably many coordinates, concatenating countably many elements of  produces an element of

produces an element of  . Thus Claim 2 can be easily verified. With above claims, we can see that

. Thus Claim 2 can be easily verified. With above claims, we can see that

Thus  is a closed subspace of

is a closed subspace of  . Any closed subspace of a collectionwise normal space is collectionwise normal. We have established that

. Any closed subspace of a collectionwise normal space is collectionwise normal. We have established that  is normal.

is normal.

____________________________________________________________________

The normality in the powers of

We have established that  is not normal. Hence any higher uncountable power of

is not normal. Hence any higher uncountable power of  is not normal. We have also established that

is not normal. We have also established that  , the countable power of

, the countable power of  is normal (in fact collectionwise normal). Hence any finite power of

is normal (in fact collectionwise normal). Hence any finite power of  is normal. However

is normal. However  is not hereditarily normal. One of the exercises below is to show that

is not hereditarily normal. One of the exercises below is to show that  is not hereditarily normal.

is not hereditarily normal.

Theorem 2 can be generalized as follows:

Theorem 4

Let  be a countably compact space has an f.i.p. collection

be a countably compact space has an f.i.p. collection  of closed sets such that

of closed sets such that  . Then

. Then  is not normal where

is not normal where  .

.

The proof of Theorem 2 would go exactly like that of Theorem 2. Consider the following two theorems.

Theorem 5

Let  be a countably compact space that is not compact. Then there exists a cardinal number

be a countably compact space that is not compact. Then there exists a cardinal number  such that

such that  is not normal and

is not normal and  is normal for all cardinal number

is normal for all cardinal number  .

.

By the non-compactness of  , there exists an f.i.p. collection

, there exists an f.i.p. collection  of closed subsets of

of closed subsets of  such that

such that  . Let

. Let  be the least cardinality of such an f.i.p. collection. By Theorem 4, that

be the least cardinality of such an f.i.p. collection. By Theorem 4, that  is not normal. Because

is not normal. Because  is least, any smaller power of

is least, any smaller power of  must be normal.

must be normal.

Theorem 6

Let  be a space that is not countably compact. Then

be a space that is not countably compact. Then  is not normal for any cardinal number

is not normal for any cardinal number  .

.

Since the space  in Theorem 6 is not countably compact, it would contain a closed and discrete subspace that is countable. By a theorem of A. H. Stone,

in Theorem 6 is not countably compact, it would contain a closed and discrete subspace that is countable. By a theorem of A. H. Stone,  is not normal. Then

is not normal. Then  is a closed subspace of

is a closed subspace of  .

.

Thus between Theorem 5 and Theorem 6, we can say that for any non-compact space  ,

,  is not normal for some cardinal number

is not normal for some cardinal number  . The

. The  from either Theorem 5 or Theorem 6 is at least

from either Theorem 5 or Theorem 6 is at least  . Interestingly for some spaces, the

. Interestingly for some spaces, the  can be much smaller. For example, for the Sorgenfrey line,

can be much smaller. For example, for the Sorgenfrey line,  . For some spaces (e.g. the Michael line),

. For some spaces (e.g. the Michael line),  .

.

Theorems 4, 5 and 6 are related to a theorem that is due to Noble.

Theorem 7 (Noble)

If each power of a space  is normal, then

is normal, then  is compact.

is compact.

A proof of Noble’s theorem is given in this earlier post, the proof of which is very similar to the proof of Theorem 2 given above. So the above discussion the normality of powers of  is just another way of discussing Theorem 7. According to Theorem 7, if

is just another way of discussing Theorem 7. According to Theorem 7, if  is not compact, some power of

is not compact, some power of  is not normal.

is not normal.

The material discussed in this post is excellent training ground for topology. Regarding powers of countably compact space and product of countably compact spaces, there are many topics for further discussion/investigation. One possibility is to examine normality in  for more examples of countably compact non-compact

for more examples of countably compact non-compact  . One particular interesting example would be a countably compact non-compact

. One particular interesting example would be a countably compact non-compact  such that the least power

such that the least power  for non-normality in

for non-normality in  is more than

is more than  . A possible candidate could be the second uncountable ordinal

. A possible candidate could be the second uncountable ordinal  . By Theorem 2,

. By Theorem 2,  is not normal. The issue is whether the

is not normal. The issue is whether the  power

power  and countable power

and countable power  are normal.

are normal.

____________________________________________________________________

Exercises

Exercise 1

Show that  is not hereditarily normal.

is not hereditarily normal.

Exercise 2

Show that the mapping  in Claim 3 in the proof of Theorem 3 is a homeomorphism.

in Claim 3 in the proof of Theorem 3 is a homeomorphism.

Exercise 3

The proof of Theorem 3 shows that the space  is a closed subspace of the

is a closed subspace of the  -product of the real line. Show that

-product of the real line. Show that  can be embedded in the

can be embedded in the  -product of arbitrary spaces.

-product of arbitrary spaces.

For each  , let

, let  be a space with at least two points. Let

be a space with at least two points. Let  . The

. The  -product of the spaces

-product of the spaces  is the following subspace of the product space

is the following subspace of the product space  .

.

The point  is the center of the

is the center of the  -product. Show that the space

-product. Show that the space  contains

contains  as a closed subspace.

as a closed subspace.

Exercise 4

Find a direct proof of Theorem 3, that  is normal.

is normal.

____________________________________________________________________

, which is the product of

with the interval topology (ordered topology) and the product space

where

is of course the unit interval

. The notation of

, the first uncountable ordinal, in Steen and Seebach is

.

is the product space

where

is

and

is the unit interval

for all

. Thus in this product space, all factors except for one factor is the unit interval and the lone non-compact factor is the first uncountable ordinal. The factor of

makes this product space an interesting example.

that are covered in [2] are:

is Hausdorff and completely regular.

is countably compact.

is neither compact nor sequentially compact.

is neither separable, Lindelof nor

-compact.

is not first countable.

is locally compact.

is not normal.

has a dense subspace that is normal.

is an example of a completely regular space that is not normal. Not being a normal space,

is then not metrizable. Of course there are other ways to show that

is not metrizable. One is that neither of the two factors

or

is metrizable. Another is that

is not first countable.

is not normal

is normal. The fact that it was not discussed in [2] could be that the tool for answering the normality question was not yet available at the time [2] was originally published, though we do not know for sure. It turns out that the tool became available in the paper [1] published a few years after the publication of [2]. The key to showing the normality (or the lack of) in the example

is to show whether the second factor

is a countably tight space.

, the product

is normal if and only if

is countably tight. For a proof of this theorem, see here. Thus the normality of the space

(or the lack of) hinges on whether the compact factor

is countably tight.

is countably tight (or has countable tightness) if for each

and for each

, there exists some countable

such that

. The definitions of tightness in general and countable tightness in particular are discussed here.

is not countably tight, we define

as follows. For each finite

, define

such that

maps

to 1 and maps

to 0. Let

be the set of

for all possible finite

. Let

be defined by

for all

.

. We claim that for any countable

,

. Let

be countable where each

is finite. Then choose

. Consider the open set

where

for

and

. Then

and

. Thus

. This shows that the product space

is not countably tight.

is not normal.

has a dense subspace that is normal

is not normal, a natural question is whether it has a dense subspace that is normal. Consider the subspace

where

is the

-product

where

is the space of all

such that for each

,

for at most countably many

.

is dense in the product space

. Thus

is dense in

. The space

is normal since the

-product of separable metric spaces is normal (see here). Furthermore,

can be embedded as a closed subspace of

. Then

is homeomorphic to a closed subspace of

. Note that

. Since

can be embedded as a closed subspace of the normal space

, the space

is normal.

2015 Dan Ma