This is a discussion on a compact space called Helly space. The discussion here builds on the facts presented in Counterexample in Topology [2]. Helly space is Example 107 in [2]. The space is named after Eduard Helly.

Let be the closed unit interval with the usual topology. Let

be the set of all functions

. The set

is endowed with the product space topology. The usual product space notation is

or

where each

. As a product of compact spaces,

is compact.

Any function is said to be increasing if

for all

(such a function is usually referred to as non-decreasing). Helly space is the subspace

consisting of all increasing functions. This space is Example 107 in Counterexample in Topology [2]. The following facts are discussed in [2].

- The space

is compact.

- The space

is first countable (having a countable base at each point).

- The space

is separable.

- The space

has an uncountable discrete subspace.

From the last two facts, Helly space is a compact non-metrizable space. Any separable metric space would have countable spread (all discrete subspaces must be countable).

The compactness of stems from the fact that

is a closed subspace of the compact space

.

Further Discussion

Additional facts concerning Helly space are discussed.

- The product space

is normal.

- Helly space

contains a copy of the Sorgenfrey line.

- Helly space

is not hereditarily normal.

The space is the space of all countable ordinals with the order topology. Recall

is the product space

. The product space

is Example 106 in [2]. This product is not normal. The non-normality of

is based on this theorem: for any compact space

, the product

is normal if and only if the compact space

is countably tight. The compact product space

is not countably tight (discussed here). Thus

is not normal. However, the product

is normal since Helly space

is first countable.

To see that contains a copy of the Sorgenfrey line, consider the functions

defined as follows:

for all . Let

. Consider the mapping

defined by

. With the domain

having the Sorgenfrey topology and with the range

being a subspace of Helly space, it can be shown that

is a homeomorphism.

With the Sorgenfrey line embedded in

, the square

contains a copy of the Sorgenfrey plane

, which is non-normal (discussed here). Thus the square of Helly space is not hereditarily normal. A more interesting fact is that Helly space is not hereditarily normal. This is discussed in the next section.

Finding a Non-Normal Subspace of Helly Space

As before, is the product space

where

and

is Helly space consisting of all increasing functions in

. Consider the following two subspaces of

.

The subspace is a closed subset of

, hence compact. We claim that subspace

is separable and has a closed and discrete subset of cardinality continuum. This means that the subspace

is not a normal space.

First, we define a discrete subspace. For each with

, define

as follows:

Let . The set

as a subspace of

is discrete. Of course it is not discrete in

since

is compact. In fact, for any

,

(closure taken in

). However, it can be shown that

is closed and discrete as a subset of

.

We now construct a countable dense subset of . To this end, let

be a countable base for the usual topology on the unit interval

. For example, we can let

be the set of all open intervals with rational endpoints. Furthermore, let

be a countable dense subset of the open interval

(in the usual topology). For convenience, we enumerate the elements of

and

.

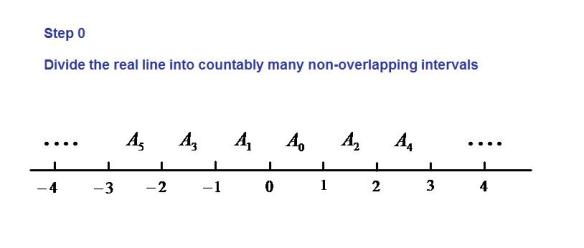

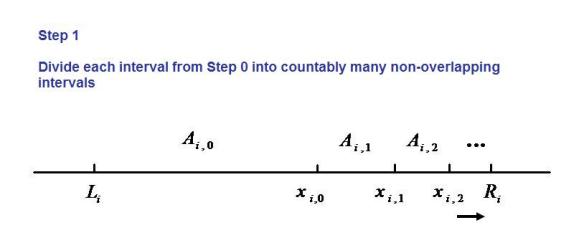

We also need the following collections.

For each and for each

with

, we would like to arrange the elements in increasing order, notated as follow:

For the set , we have

. For the set

,

is to the left of

for

. Note that elements of

are pairwise disjoint. Furthermore, write

. If

, then

. If

, then

.

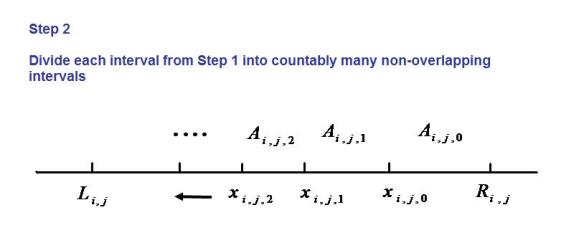

For each and

as detailed above, we define a function

as follows:

The following diagram illustrates the definition of when both

and

have 4 elements.

Let be the set of

over all

and

. The set

is a countable set. It can be shown that

is dense in the subspace

. In fact

is dense in the entire Helly space

.

To summarize, the subspace is separable and has a closed and discrete subset of cardinality continuum. This means that

is not normal. Hence Helly space

is not hereditarily normal. According to Jones’ lemma, in any normal separable space, the cardinality of any closed and discrete subspace must be less than continuum (discussed here).

Remarks

The preceding discussion shows that both Helly space and the square of Helly space are not hereditarily normal. This is actually not surprising. According to a theorem of Katetov, for any compact non-metrizable space , the cube

is not hereditarily normal (see Theorem 3 in this post). Thus a non-normal subspace is found in

,

or

. In fact, for any compact non-metric space

, an excellent exercise is to find where a non-normal subspace can be found. Is it in

, the square of

or the cube of

? In the case of Helly space

, a non-normal subspace can be found in

.

A natural question is: is there a compact non-metric space such that both

and

are hereditarily normal and

is not hereditarily normal? In other words, is there an example where the hereditarily normality fails at dimension 3? If we do not assume extra set-theoretic axioms beyond ZFC, any compact non-metric space

is likely to fail hereditarily normality in either

or

. See here for a discussion of this set-theoretic question.

Reference

- Kelly, J. L., General Topology, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1955.

- Steen, L. A., Seebach, J. A., Counterexamples in Topology, Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1995.

Dan Ma topology

Daniel Ma topology

Dan Ma math

Daniel Ma mathematics

2019 – Dan Ma