We discuss the completeness of the real line. With respect to the real line, completeness refers to the fact that the real line has no holes or gaps. There are many ways to state what it means for the real line to be complete. In this post, we state it using the least upper bound property. Then we show that this property is equivalent to a host of other statements. This discussion will be useful for subsequent posts where we discuss compactness and other properties of the real line.

This is a post on introductory topology. Concepts discussed here are basic notions found in beginning topology courses and elementary analysis courses. For the readers who are taking math courses that transition their math career from calculation to proving of theorems, we encourage such readers to think about the concepts and theorems discussed here before reading the proofs.

Let  . By an upper bound of the set

. By an upper bound of the set  , we mean a real number number

, we mean a real number number  such that

such that  for all

for all  . If a set has an upper bound, we say that it is bounded above. Similarly, a lower bound of the set

. If a set has an upper bound, we say that it is bounded above. Similarly, a lower bound of the set  is a real number

is a real number  such that

such that  for all

for all  . If a set has a lower bound, then we say it is bounded below. If a set is both bounded above and bounded below, it is said to be bounded.

. If a set has a lower bound, then we say it is bounded below. If a set is both bounded above and bounded below, it is said to be bounded.

Suppose  is bounded above. By a least upper bound of the set

is bounded above. By a least upper bound of the set  , we mean a real number

, we mean a real number  that is the smallest among all the upper bounds of

that is the smallest among all the upper bounds of  , that is, the number

, that is, the number  is itself an upper bound of

is itself an upper bound of  and for each upper bound

and for each upper bound  of

of  , we have

, we have  . It turns out that if a set has a least upper bound, then it is unique. Suppose

. It turns out that if a set has a least upper bound, then it is unique. Suppose  and

and  are both least upper bounds of

are both least upper bounds of  . Then we have

. Then we have  and

and  . This imples

. This imples  .

.

Similarly, the number  is the greatest lower bound of the set

is the greatest lower bound of the set  if the number

if the number  is a lower bound of

is a lower bound of  and for each lower bound

and for each lower bound  of

of  , we have

, we have  . As with the least upper bound, if a set has a greatest lower bound, it has only one greatest lower bound. The following is the statement of the least upper bound property:

. As with the least upper bound, if a set has a greatest lower bound, it has only one greatest lower bound. The following is the statement of the least upper bound property:

The Least Upper Bound Property. Every subset of the real line that is bounded above has a least upper bound.

In the discussion about the real line in this post and in subsequent posts, we will take the least upper bound property as a given. In the remainder of this post, we show that this property is equivalent to several other statements about the real line. Thus we could have taken any one of those statements as a given. We also have a statement that can be called the greatest lower bound property: every subset of the real line that is bounded below has a greatest lower bound. This statement is also equivalent to the least upper bound property.

For the definition of open intervals, open sets and closed sets, see the previous post The Euclidean topology of the real line (2). We have some more definitions.

Definitions

- Let

. Let

. Let  . The point

. The point  is a limit point of

is a limit point of  if every open set containing

if every open set containing  contains a point of

contains a point of  different from

different from  .

.

- Let

be the set of all positive integers. A sequence of real numbers is a function

be the set of all positive integers. A sequence of real numbers is a function  . We usually express

. We usually express  as

as  and the function

and the function  is expressed as

is expressed as  or

or  .

.

- Given a sequence of real numbers

, consider an infinite subset

, consider an infinite subset  . If we only consider terms of the sequence

. If we only consider terms of the sequence  where the subscript

where the subscript  , then it is called a subsequence of

, then it is called a subsequence of  . The notation is

. The notation is  .

.

- A sequence

converges if there is a number

converges if there is a number  such that for every open interval

such that for every open interval  containing

containing  , there is a positive integer

, there is a positive integer  such that

such that  for all

for all  . The point

. The point  is said to be the limit of

is said to be the limit of  . We use the notation

. We use the notation  or

or  .

.

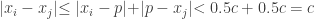

- A sequence

is said to be a Cauchy sequence if for each

is said to be a Cauchy sequence if for each  , there is a positive integer

, there is a positive integer  such that

such that  for all

for all  .

.

- A sequence

is said to be bounded if the set of the terms of the sequence

is said to be bounded if the set of the terms of the sequence  is a bounded set, or equivalently there is a positive number

is a bounded set, or equivalently there is a positive number  such that for each term

such that for each term  we have

we have  .

.

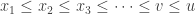

- A sequence

is said to be nondecreasing if

is said to be nondecreasing if  for each

for each  . For such a sequence, we have

. For such a sequence, we have  .

.

- A sequence

is said to be nonincreasing if

is said to be nonincreasing if  for each

for each  . For such a sequence, we have

. For such a sequence, we have  .

.

- A sequence

is said to be monotonic if it is either nondecreasing or nonincreasing.

is said to be monotonic if it is either nondecreasing or nonincreasing.

One of the properties that is equivalent to the least upper bound property is the nested interval property. It is stated as follows:

The Nested Interval Property. Suppose that for each positive interger  we have closed intervals

we have closed intervals ![I_n=[a_n,b_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=I_n%3D%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) such that

such that

![\displaystyle [a_1,b_1] \supset [a_2,b_2] \supset [a_3,b_3] \supset \cdots](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle+%5Ba_1%2Cb_1%5D+%5Csupset+%5Ba_2%2Cb_2%5D+%5Csupset+%5Ba_3%2Cb_3%5D+%5Csupset+%5Ccdots&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002)

and  .

.

Then the intersection of the intervals  has only one point, i.e.

has only one point, i.e. ![\bigcap \limits_{n=1}^{\infty} [a_n,b_n]=\left\{x\right\}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbigcap+%5Climits_%7Bn%3D1%7D%5E%7B%5Cinfty%7D+%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D%3D%5Cleft%5C%7Bx%5Cright%5C%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

We incorporate some observations about sequences into a lemma, which is used in proving the main theorem below.

Lemma

- If a sequence

of real numbers converges, then the limit is unique.

of real numbers converges, then the limit is unique.

- If a sequence

of real numbers converges, then the sequence is a Cauchy sequence.

of real numbers converges, then the sequence is a Cauchy sequence.

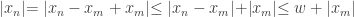

- If

is a Cauchy sequence of real numbers, then it is bounded.

is a Cauchy sequence of real numbers, then it is bounded.

- If a sequence

of real numbers converges, then the sequence is bounded.

of real numbers converges, then the sequence is bounded.

- If the real number

is a limit point of the set

is a limit point of the set  , then there is a sequence

, then there is a sequence  of points of

of points of  such that

such that  converges to

converges to  .

.

Proof

Note that if a sequence converges to a point

Note that if a sequence converges to a point  , then every open interval containing

, then every open interval containing  would contain all but finitely many terms in the sequence. Point

would contain all but finitely many terms in the sequence. Point  in the lemma stems from the fact that every pair of distinct numbers in the real line are contained in two disjoint open intervals. For

in the lemma stems from the fact that every pair of distinct numbers in the real line are contained in two disjoint open intervals. For  , we have disjoint open intervals

, we have disjoint open intervals  and

and  where

where  . If both

. If both  and

and  are limits of the same sequence, then each of these two disjoint open intervals would contain all but finitely many terms in the sequence, which is impossible.

are limits of the same sequence, then each of these two disjoint open intervals would contain all but finitely many terms in the sequence, which is impossible.

Let

Let  be a convergent sequence with

be a convergent sequence with  as a limit. For each

as a limit. For each  , we have

, we have  such that

such that  for all

for all  . Thus for all

. Thus for all  , we have:

, we have:

The above shows that the sequence is a Cauchy sequence.

Let

Let  be a Cauchy sequence. For

be a Cauchy sequence. For  , there is some positive integer

, there is some positive integer  such that for all

such that for all  , we have

, we have  . Let

. Let  be the maximum of the following real numbers:

be the maximum of the following real numbers:

Then for each term  in the sequence we have

in the sequence we have  . Furthermore, we have:

. Furthermore, we have:

Thus  is an upper bound of the cauchy sequence in question.

is an upper bound of the cauchy sequence in question.

This follows from

This follows from  and

and  .

.

Let

Let  be a limit point of the set

be a limit point of the set  . For each positive integer

. For each positive integer  , let

, let  such that

such that  . Then

. Then  .

.

Theorem

The following statements are equivalent:

- The least upper bound property.

- Every bounded montonic sequence of real numbers converges.

- The nested interval property.

- (Bolzano-Weierstrass Theorem) Every infinite set of real numbers that is also bounded has a limit point.

- Every bounded sequence of real numbers has a subsequence that converges.

- Every Cauchy sequence of real numbers converges.

Remark

In some texts such as ![[1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) , completeness is defined in terms of Cauchy sequences (condition

, completeness is defined in terms of Cauchy sequences (condition  ). In a metric space, a Cauchy sequence is one where the distances of the successive terms diminishes to zero. Any space with a metric such that every Cauchy sequence converges is said to be a complete metric space. Thus the real line with the Euclidean metric is an example of a complete metric space.

). In a metric space, a Cauchy sequence is one where the distances of the successive terms diminishes to zero. Any space with a metric such that every Cauchy sequence converges is said to be a complete metric space. Thus the real line with the Euclidean metric is an example of a complete metric space.

In some texts, the nested interval property is taken as the definition of completeness. In a general metric space, the nested intervals are taken to be closed and bounded sets (bounded by the metric in question) with diameters  .

.

The least upper bound property is based on an order relation and is not applicable to metric spaces in general. Conditions  do not hold in metric spaces in general but hold in Euclidean spaces.

do not hold in metric spaces in general but hold in Euclidean spaces.

Proof

We establish the equivalences by proving  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  .

.

We show that every bounded nondecreasing sequence  of real numbers converges. For the proof that every bounded nonincreasing sequence of real numbers converges, use a similar proof by working with the greatest lower bound. Suppose that the sequence

of real numbers converges. For the proof that every bounded nonincreasing sequence of real numbers converges, use a similar proof by working with the greatest lower bound. Suppose that the sequence  is nondecreasing and bounded. Let

is nondecreasing and bounded. Let  be an upper bound of the set

be an upper bound of the set  . By the least upper bound property, the set

. By the least upper bound property, the set  has a least upper bound

has a least upper bound  . We have the following:

. We have the following:

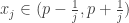

We claim that the number  is the limit of the sequence

is the limit of the sequence  . Let

. Let  be an open interval containing

be an open interval containing  , i.e,

, i.e,  . There must be some term

. There must be some term  of the sequence such that

of the sequence such that  . Otherwise,

. Otherwise,  would be an upper bound, which is impossible since

would be an upper bound, which is impossible since  is the least upper bound. Since the sequence is nondecreasing, we have

is the least upper bound. Since the sequence is nondecreasing, we have  for all

for all  . Thus

. Thus  is established.

is established.

Suppose we have a sequence of nested intervals ![[a_n,b_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) such that the widths of the intervals

such that the widths of the intervals  . The sequence

. The sequence  is nondecreasing and has an upper bound (e.g.

is nondecreasing and has an upper bound (e.g.  ). By

). By  , this sequence converges, say to the limit

, this sequence converges, say to the limit  . On the other hand, the sequence

. On the other hand, the sequence  is nonincreasing and has an lower bound (e.g.

is nonincreasing and has an lower bound (e.g.  ). Thus this sequence converges, say to the limit

). Thus this sequence converges, say to the limit  .

.

Note that ![[a,b] \subset [a_n,b_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba%2Cb%5D+%5Csubset+%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) for each

for each  . Since

. Since  ,

,  .

.

Suppose  is an infinite set and is bounded. We produce a limit point by the approach of “divide and conquer”. Suppose that

is an infinite set and is bounded. We produce a limit point by the approach of “divide and conquer”. Suppose that ![A \subset [a,b]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=A+%5Csubset+%5Ba%2Cb%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Let

. Let  and

and  . Divide this interval into two equal halves,

. Divide this interval into two equal halves, ![[a_1,m]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_1%2Cm%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and

and ![[m,b_1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Bm%2Cb_1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) where

where  . Since

. Since  is infinite, one of these two halves has to contain infinitely many points of

is infinite, one of these two halves has to contain infinitely many points of  . Otherwise,

. Otherwise,  is a finite set. Pick a half that has infinitely many points of

is a finite set. Pick a half that has infinitely many points of  and let

and let  be the left endpoint of this interval and

be the left endpoint of this interval and  be the right endpoint.

be the right endpoint.

Continue this process inductively. Suppose ![[a_n,b_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has been chosen. Then we divide it into

has been chosen. Then we divide it into ![[a_n,m]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_n%2Cm%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and

and ![[m,b_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Bm%2Cb_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) where

where  . Pick a half that has infinitely many points of

. Pick a half that has infinitely many points of  and let

and let  be the left endpoint and

be the left endpoint and  be the right endpoint. Then we have a nested sequence of decreasing intervals. Since we keep dividing each stage into halves, the lengths of the intervals

be the right endpoint. Then we have a nested sequence of decreasing intervals. Since we keep dividing each stage into halves, the lengths of the intervals  approaches

approaches  . By the nested interval property, there is only one point

. By the nested interval property, there is only one point  in the intersection of the intervals.

in the intersection of the intervals.

The point  is a limit point of

is a limit point of  . To see this, let

. To see this, let  be an open interval containing

be an open interval containing  . Then for some sufficiently large

. Then for some sufficiently large  we have

we have ![[a_n,b_n] \subset (s,t)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D+%5Csubset+%28s%2Ct%29&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Then the open interval

. Then the open interval  contains infinitely many points of

contains infinitely many points of  .

.

Suppose  is a bounded sequence of real numbers. We aim to produce a subsequence that converges. Let

is a bounded sequence of real numbers. We aim to produce a subsequence that converges. Let  be the set of all terms in the sequence. The set

be the set of all terms in the sequence. The set  is expressed as the following:

is expressed as the following:

Suppose  is a finite set. Then starting at some integer

is a finite set. Then starting at some integer  ,

,  . The sequence

. The sequence  is a subsequence that is a constant sequence (thus converges). Suppose

is a subsequence that is a constant sequence (thus converges). Suppose  is an infinite set. By

is an infinite set. By  ,

,  has a limit point. Let

has a limit point. Let  be one limit point of

be one limit point of  . By

. By  in the lemma, there is a sequence of points from

in the lemma, there is a sequence of points from  converging to

converging to  . This sequence would be a subsequence of

. This sequence would be a subsequence of  .

.

By the lemma, any Cauchy sequence of real numbers is bounded. Let  be a Cauchy sequence of real numbers. By

be a Cauchy sequence of real numbers. By  , there is a subsequence

, there is a subsequence  that converges. Let

that converges. Let  be the limit of the subsequence. Note that

be the limit of the subsequence. Note that  is also the limit of the original sequence

is also the limit of the original sequence  .

.

Let ![[a_n,b_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) be a sequence of intervals satisfying the nested interval property. Then

be a sequence of intervals satisfying the nested interval property. Then  is a Cauchy sequence, which converges, say to the point

is a Cauchy sequence, which converges, say to the point  . Then

. Then  is the lone point that belongs to each

is the lone point that belongs to each ![[a_n,b_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

Suppose that  is bounded above. Let

is bounded above. Let  be the set of all upper bounds of

be the set of all upper bounds of  . Note that for each

. Note that for each  ,

,  is a lower bound of

is a lower bound of  . Pick

. Pick  and

and  . Let

. Let  and

and  . If there are only finitely many point of

. If there are only finitely many point of  in between

in between  and

and  , then the smallest points of

, then the smallest points of  would be the least upper bound of

would be the least upper bound of  and we are done. So assume that

and we are done. So assume that ![[a_1,b_1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_1%2Cb_1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) contains infinitely many points of

contains infinitely many points of  (i.e. infinitely many upper bounds of

(i.e. infinitely many upper bounds of  ).

).

Consider ![[a_1,m]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_1%2Cm%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and

and ![[m,b_1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Bm%2Cb_1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) where

where  . If the left interval

. If the left interval ![[a_1,m]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_1%2Cm%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) contains upper bounds of

contains upper bounds of  , we assume that that it has infinitely many of them (otherwise, the minimum would be the least upper bound and we are done). Choose one of these intervals that contains infinitely many points of

, we assume that that it has infinitely many of them (otherwise, the minimum would be the least upper bound and we are done). Choose one of these intervals that contains infinitely many points of  . If both intervals contain infinitely many points of

. If both intervals contain infinitely many points of  , we choose the leftmost one. Then we let

, we choose the leftmost one. Then we let  be the left endpoint of the chosen interval and

be the left endpoint of the chosen interval and  be the right endpoint of the interval. We observe that to the left of

be the right endpoint of the interval. We observe that to the left of  , there are no upper bounds of

, there are no upper bounds of  (points of

(points of  ).

).

Continue this process inductively, making sure that in each step we divide the previous interval ![[a_n,b_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) into two equal halves. If the left interval contains upper bounds of

into two equal halves. If the left interval contains upper bounds of  , we assume that it has infinitely many of them (otherwise, we stop at this inductive step). We choose the first half interval that contains infinitely many upper bounds of

, we assume that it has infinitely many of them (otherwise, we stop at this inductive step). We choose the first half interval that contains infinitely many upper bounds of  and denote it by

and denote it by ![[a_{n+1},b_{n+1}]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_%7Bn%2B1%7D%2Cb_%7Bn%2B1%7D%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Observe that to the left of

. Observe that to the left of  , there are no upper bounds of

, there are no upper bounds of  .

.

As indicated in the induction step, if we can stop at any one of the step, we would have a least upper bound of  and we are done. Otherwise, we have a nested sequence of intervals

and we are done. Otherwise, we have a nested sequence of intervals ![[a_n,b_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) such that the widths of the intervals

such that the widths of the intervals  . Then the intervals have exactly one point

. Then the intervals have exactly one point  in the intersection.

in the intersection.

We claim that  is the desired least upper bound of

is the desired least upper bound of  . First of all, there is no upper bounds of

. First of all, there is no upper bounds of  to the left of

to the left of  . This stems from the observation that no upper bounds of

. This stems from the observation that no upper bounds of  can be found at the left side of each

can be found at the left side of each  and the fact that

and the fact that  converges to

converges to  . Thus if

. Thus if  is an upper bound of

is an upper bound of  , then

, then  is the least upper bound. Note that

is the least upper bound. Note that  is a limit point of

is a limit point of  since every interval

since every interval ![[a_n,b_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ba_n%2Cb_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) contains infinitely many points of

contains infinitely many points of  . If

. If  is not an upper bound of

is not an upper bound of  , then there is some point

, then there is some point  of

of  such that

such that  . Then the interval

. Then the interval  contains no points of

contains no points of  (upper bounds of

(upper bounds of  ). This constradicts the fact that

). This constradicts the fact that  is a limit point of

is a limit point of  . So

. So  must be an upper bound of

must be an upper bound of  . This establishes the least upper bound property.

. This establishes the least upper bound property.

Reference

- Rudin, W., Principles of Mathematical Analysis, Third Edition, 1976, McGraw-Hill, New York.

of the real line is a perfect set if it is closed and every point of

is a limit point of

. In the previous post Perfect sets and Cantor sets, II, we demonstrate a procedure for constructing a Cantor set out of any nonempty perfect set. In another post The Lindelof property of the real line, we show that every uncountable subset

of the real line contains at least one of its limit points. Thus all but countably many points of

are limit points of

. Consequently, for any uncountable closed subset

of the real line, all but countably many points of

are limit points of

. By removing the countably many non-limit points (isolated points), we have a perfect set.