The Sorgenfrey line is a well known topological space. It is the real number line with open intervals defined as sets of the form . Though this is a seemingly small tweak, it generates a vastly different space than the usual real number line. In this post, we look at the Sorgenfrey line from the continuous function perspective, in particular, the continuous functions that map the Sorgenfrey line into the real number line. In the process, we obtain insight into the space of continuous functions on the Sorgenfrey line.

The next post is a continuation on the theme of drawing Sorgenfrey continuous functions.

The Sorgenfrey Line

Let denote the real number line. The usual open intervals are of the form

. The union of such open intervals is called an open set. If more than one topologies are considered on the real line, these open sets are referred to as the usual open sets or Euclidean open sets (on the real line). The open intervals

form a base for the usual topology on the real line. One important fact abut the usual open sets is that the usual open sets can be generated by the intervals

where both end points are rational numbers. Thus the usual topology on the real line is said to have a countable base.

Now tweak the usual topology by calling sets of the form open intervals. Then form open sets by taking unions of all such open intervals. The collection of such open sets is called the Sorgenfrey topology (on the real line). The real number line

with the Sorgenfry topology is called the Sorgenfrey line, denoted by

. The Sorgenfrey line has been discussed in this blog, starting with this post. This post examines continuous functions from

into the real line. In the process, we gain insight on the space of continuous functions defined on

.

Note that any usual open interval is the union of intervals of the form

. Thus any usual (Euclidean) open set is an open set in the Sorgenfrey line. Thus the usual topology (on the real line) is contained in the Sorgenfrey topology, i.e. the usual topology is a weaker (coarser) topology.

Let be the set of all continuous functions

where the domain is the real number line with the usual topology. Let

be the set of all continuous functions

where the domain is the Sorgenfrey line. In both cases, the range is always the number line with the usual topology. Based on the preceding paragraph, any continuous function

is also continuous with respect to the Sorgenfrey line, i.e.

.

Pictures of Continuous Functions

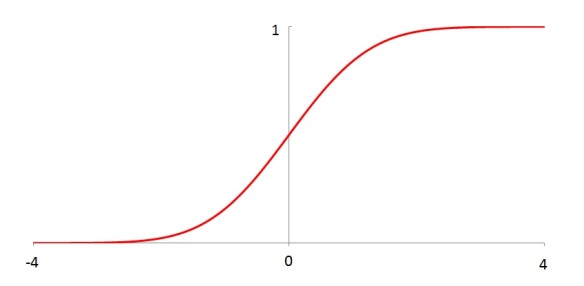

Consider the following two continuous functions.

The first one (Figure 1) is the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the standard normal distribution. The second one (Figure 2) is the CDF of the uniform distribution on the interval where

. Both of these are continuous in the usual Euclidean topology (in the domain). Such graphs would make regular appearance in a course on probability and statistics. They also show up in a calculus course as an everywhere differentiable curve (Figure 1) and as a differentiable curve except at finitely many points (Figure 2). Both of these functions can also be regarded as continuous functions on the Sorgenfrey line.

Consider a function that is continuous in the Sorgenfrey line but not continuous in the usual topology.

Figure 3 is a function that maps the interval to -1 and maps the interval

to 1. It is not continuous in the usual topology because of the jump at

. But it is a continuous function when the domain is considered to be the Sorgenfrey line. Because of the open intervals being

, continuous functions defined on the Sorgenfrey line are right continuous.

The cumulative distribution function of a discrete probability distribution is always right continuous, hence continuous in the Sorgenfrey line. Here’s an example.

Figure 4 is the CDF of the uniform distribution on the finite set , where each point has probability 0.2. There is a jump of height 0.2 at each of the points from 0 to 4. Figure 3 and Figure 4 are step functions. As long as the left point of a step is solid and the right point is hollow, the step functions are continuous on the Sorgenfrey line.

The take away from the last four figures is that the real-valued continuous functions defined on the Sorgenfrey line are right continuous and that step functions (with the left point solid and the right point hollow) are Sorgenfrey continuous.

A Family of Sorgenfrey Continuous Functions

The four examples of continuous functions shown above are excellent examples to illustrate the Sorgenfrey topology. We now introduce a family of continuous functions for

. These continuous functions will lead to additional insight on the function space whose domain space is the Sorgenfrey line.

For any , the following gives the definition and the graph of the function

.

Function Space on the Sorgenfrey Line

This is the place where we switch the focus to function space. The set is a subset of the product space

. So we can consider

as a topological space endowed with the topology inherited as a subspace of

. This topology on

is called the pointwise convergence topology and

with the product subspace topology is denoted by

. See here for comments on how to work with the pointwise convergence topology.

For the present discussion, all we need is some notation on a base for . For

, and for any open interval

(open in the usual topology of the real number line), let

. Then the collection of intersections of finitely many

would form a base for

.

The following is the main fact we wish to establish.

The function space contains a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum. In particular, the set

is a closed and discrete subspace of

.

The above result will derive several facts on the function space , which are discussed in a section below. More interestingly, the proof of the fact that

is a closed and discrete subspace of

is based purely on the definition of the functions

and the Sorgenfrey topology. The proof given below does not use any deep or high powered results from function space theory. So it should be a nice exercise on the Sorgenfrey topology.

I invite readers to either verify the fact independently of the proof given here or follow the proof closely. Lots of drawing of the functions on paper will be helpful in going over the proof. In this one instance at least, drawing continuous functions can help gain insight on function spaces.

Working out the Proof

The following diagram was helpful to me as I worked out the different cases in showing the discreteness of the family . The diagram is a valuable aid in convincing myself that a given case is correct.

Now the proof. First, is relatively discrete in

. We show that for each

, there is an open set

containing

such that

does not contain

for any

. To this end, let

where

and

are the open intervals

and

. With Figure 6 as an aid, it follows that for

,

and for

,

.

The open set contains

, the function in the middle of Figure 6. Note that for

,

and

. Thus

. On the other hand, for

,

and

. Thus

. This proves that the set

is a discrete subspace of

relative to

itself.

Now we show that is closed in

. To this end, we show that

-

for each

Actually, this has already been done above with points that are in

. One thing to point out is that the range of

is

. As we consider

, we only need to consider

that maps into

. Let

. The argument is given in two cases regarding the function

.

Case 1. There exists some such that

.

We assume that and

. Then for all

,

and for all

,

. Let

. Then

and

contains no

for any

and

for any

. To help see this argument, use Figure 6 as a guide. The case that

and

has a similar argument.

Case 2. For every , we have

.

Claim. The function is constant on the interval

. Suppose not. Let

such that

. Suppose that

. Consider

. Clearly the number

is an upper bound of

. Let

be a least upper bound of

. The function

has value 1 on the interval

. Otherwise,

would not be the least upper bound of the set

. There is a sequence of points

in the interval

such that

from the left such that

for all

. Otherwise,

would not be the least upper bound of the set

.

It follows that . Otherwise, the function

is not continuous at

. Now consider the 6 points

. By the assumption in Case 2,

and

. Since

for all

,

for all

. Note that

from the right. Since

is right continuous,

, contradicting

. Thus we cannot have

.

Now suppose we have where

. Consider

. Clearly

has an upper bound, namely the number

. Let

be a least upper bound of

. The function

has value 0 on the interval

. Otherwise,

would not be the least upper bound of the set

. There is a sequence of points

in the interval

such that

from the left such that

for all

. Otherwise,

would not be the least upper bound of the set

.

It follows that . Otherwise, the function

is not continuous at

. Now consider the 6 points

. By the assumption in Case 2,

and

. Since

for all

,

for all

. Note that

from the right. Since

is right continuous,

, contradicting

. Thus we cannot have

.

The claim that the function is constant on the interval

is established. To wrap up, first assume that the function

is 1 on the interval

. Let

. It is clear that

. It is also clear from Figure 5 that

contains no

. Now assume that the function

is 0 on the interval

. Since

is Sorgenfrey continuous, it follows that

. Let

. It is clear that

. It is also clear from Figure 5 that

contains no

.

We have established that the set is a closed and discrete subspace of

.

What does it Mean?

The above argument shows that the set is a closed an discrete subspace of the function space

. We have the following three facts.

| Three Results |

|

To show that is separable, let’s look at one basic helpful fact on

. If

is a separable metric space, e.g.

, then

has quite a few nice properties (discussed here). One is that

is hereditarily separable. Thus

, the space of real-valued continuous functions defined on the number line with the pointwise convergence topology, is hereditarily separable and thus separable. Recall that continuous functions in

are also Soregenfrey line continuous. Thus

is a subspace of

. The space

is also a dense subspace of

. Thus the space

contains a dense separable subspace. It means that

is separable.

Secondly, is not hereditarily separable since the subspace

is a closed and discrete subspace.

Thirdly, is not a normal space. According to Jones’ lemma, any separable space with a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality of continuum is not a normal space (see Corollary 1 here). The subspace

is a closed and discrete subspace of the separable space

. Thus

is not normal.

Remarks

The topology of the Sorgenfrey line is vastly different from the usual topology on the real line even though the the Sorgenfrey topology is obtained by a seemingly small tweak from the usual topology. The real line is a metric space while the Sorgenfrey line is not metrizable. The real number line is connected while the Sorgenfrey line is not. The countable power of the real number line is a metric space and thus a normal space. On the other hand, the Sorgenfrey line is a classic example of a normal space whose square is not normal. See here for a basic discussion of the Sorgenfrey line.

The pictures of Sorgenfrey continuous functions demonstrated here show that the real number line and the Sorgenfrey line are also very different from a function space perspective. The function space has a whole host of nice properties: normal, Lindelof (hence paracompact and collectionwise normal), hereditarily Lindelof (hence hereditarily normal), hereditarily separable, and perfectly normal (discussed here).

Though separable, the function space contains a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum, making it not hereditarily separable and not normal.

For more information about in general and

in particular, see [1] and [2]. A different proof that

contains a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum can be found in Problem 165 in [2].

The next post is a continuation on the theme of drawing Sorgenfrey continuous functions.

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

- Tkachuk V. V., A

-Theory Problem Book, Topological and Function Spaces, Springer, New York, 2011.

2017 – Dan Ma

A strategy for finding CCC and non-separable spaces

In this post we present a general strategy for finding CCC spaces that are not separable. As illustration, we give four implementations of this strategy.

In searching for counterexamples in topology, one good place to look is of course the book by Steen and Seebach [2]. There are four examples of spaces that are CCC but not separable found in [2] – counterexamples 20, 21, 24 and 63. Counterexamples 20 and 21 are not Hausdorff. Counterexample 24 is the uncountable Fort space (it is completely normal but not perfectly normal). Counterexample 63 (Countable Complement Extension Topology) is Hausdorff but is not regular. These are valuable examples especially the last two (24 and 63). The examples discussed below expand the offerings in Steen and Seebach.

The discussion of CCC but not separable in this post does not use axioms beyond the usual axioms of set theory (i.e. ZFC). The discussion here does not touch on Suslin lines or other examples that require extra set theory. The existence of Suslin lines is independent of ZFC. A Suslin line would produce an example of a perfectly normal first countable CCC non-separable space. In models of set theory where Suslin lines do not exist, a perfectly normal first countable CCC non-separable space can also be produced using other set-theoretic assumptions. The examples discussed below are not as nice as the set-theoretic examples since they usually are not first countable and perfectly normal.

____________________________________________________________________

The countable chain conditon

A topological space is said to have the countable chain condition (to have the CCC for short) if

is a disjoint collection of non-empty open subsets of

(meaning that for any

with

, we have

), then

is countable. In other words, in a space with the CCC, there cannot be uncountably many pairwise disjoint non-empty open sets. For ease of discussion, if

has the CCC, we also say that

is a CCC space or X is CCC. A space

is separable if there exists a countable subset

of

such that

is dense in

(meaning that if

is a nonempty open subset of

, then

).

It is clear that any separable space has the CCC. In metric spaces, these two properties are equivalent. Among topological spaces in general, the two properties are not identical. Thus “CCC but not separable” is one way to distinguish between metrizable spaces and non-metrizable spaces. Even in non-metrizable spaces, “CCC but not separable” is also a way to obtain more information about the spaces being investigated.

____________________________________________________________________

The strategy

Here’s the strategy for finding CCC and not separable.

-

The strategy is to narrow the focus to spaces where “CCC and not separable” is likely to exist. Specifically, look for a space or a class of spaces such that each space in the class has the countable chain condition but is not hereditarily separable. If the non-separable subspace is also a dense subspace of the starting space, it would be “CCC and not separable.”

Any dense subspace of a CCC space always has the CCC. Thus the search focuses on the subspaces in a CCC space that are reliably CCC. The strategy is to find non-separable spaces among these dense subspaces. The search is given an assist if the space or class of spaces in question has a characteristic that delineate the “separable” from the CCC (see Example 3 and Example 4 below).

In the following sections, we illustrate four different ways to apply the strategy.

____________________________________________________________________

Example 1

The first way is a standard example found in the literature. The space to start from is the product space of separable spaces, which is always CCC. By a theorem of Ross and Stone, the product of more than continuum many separable spaces is not separable. Thus one way to get an example of CCC but not separable space is to take the product of more than continuum many separable spaces. For example, if is the cardinality of continuum, then consider

, the product of

many copies of

, or consider

where

is your favorite separable space.

____________________________________________________________________

Example 2

The second implementation of the strategy is also from taking the product of separable spaces. This time the number of factors does not have to be more than continuum. Here, we focus on one particular dense subspace of the product space, the -products. To make this clear, let’s focus on a specific example. Consider

where

is the cardinality of continuum. Consider the following subspace.

The subspace is dense in

, thus has CCC. It is straightforward to verify that

is not separable.

To implement this example, find any space which is a product space of separable spaces, each of which has at least two point (one of the points is labeled 0). The dense subspace is the

-product, which is the subspace consisting of all points that are non-zero at only countably many coordinates. The

-product has the countable chain condition since it is a dense subspace of the CCC space

. The

-product is not separable since there are uncountably many factors in the product space

and that each factor has at least two points. This idea had been implemented in this previous post.

____________________________________________________________________

Example 3

The third class of spaces is the class of Pixley-Roy spaces, which are hyperspaces. Given a space , let

be the set of all non-empty finite subsets of

. For

and for any open subset

of

, let

. The sets

over all

and

form a base for a topology on

. This topology is called the Pixley-Roy topology (or Pixley-Roy hyperspace topology). The set

with this topology is called a Pixley-Roy space.

The Pixley-Roy hyperspaces are discussed in this previous post. Whenever the ground space is uncountable,

is not a separable space. We need to identify the

that are CCC. According to the previous post on Pixley-Roy hyperspaces, for any space

with a countable network,

is CCC. Thus for any uncountable space

with a countable network, the Pixley-Roy space

is a CCC space that is not separable. The following gives a few such examples.

where

is any uncountable, separable and metrizable space.

where

is uncountable and is the continuous image of a separable metrizable space.

Spaces with countable networks are discussed in this previous post. An example of a space that is the continuous image of a separable metrizable space is the bow-tie space found this previous post. Another example is any quote space of a separable metrizable space.

____________________________________________________________________

Example 4

For the fourth implementation of the strategy, we go back to the product space of separable spaces in Example 2, with the exception that the focus is on the product of the real line . Let

be any uncountable completely regular space. The product space

always has the CCC since it is a product of separable space. Now we single out a dense subspace of

for which there is a characterization for separability, namely the subspace

, which is the set of all continuous functions from

into

. The subspace

as a topological space is usually denoted by

. For a basic discussion of

, see this previous post.

We know precisely when is separable. The following theorem captures the idea.

Theorem 1 – Theorem I.1.3 [1]

The function space is separable if and only if the domain space

has a weaker (or coarser) separable metric topology (in other words,

is submetrizable with a separable metric topology).

Based on the theorem, is separable for any separable metric space

. Other examples of separable

include spaces

that are created by tweaking the usual Euclidean topology on the real line and at the same time retaining the usual real line topology as a weaker topology, e.g. the Sorgenfrey line and the Michael line. Thus

would be separable if

is a space such as the Sorgenfrey line or the Michael line. For our purpose at hand, we need to look for spaces that are not like the Sorgenfrey line or the Michael line. Here’s some examples of spaces

that have no weaker separable metric topology.

- Any compact space

that is not metrizable.

- The space

, the first uncountable ordinal with the order topology.

- Any space

where

is not separable.

The function space for any one of the above three spaces has the CCC but is not separable. It is well known that any compact space with a weaker metrizable topology is metrizable. Some examples for compact

are: the first uncountable successor ordinal

, the double arrow space, and the product space

.

It can be shown that is not separable (see this previous post). The last example is due to the following theorem.

Theorem 2 – Theorem I.1.4 [1]

The function space has a weaker (or coarser) separable metric topology if and only if the domain space

is separable.

Thus picking a non-separable space would guarantee that

has no weaker separable metric topology. As a result,

is a CCC and not separable space.

Interestingly, Theorem 1 and Theorem 2 show a duality existing between the property of having a weaker separable metric topology and the property of being separable. The two theorems allow us to switch the two properties between the domain space and the function space.

____________________________________________________________________

Remarks

Another interesting point to make is that Theorem 1 and Theorem 2 together allow us to “buy one get one free.” Once we obtain a space that is CCC and not separable from any one of the avenues discussed here, the function space

has no weaker separable metric topology (by Theorem 2) and the function space

is another example of CCC and not separable.

The strategy discussed above unifies all four examples. Undoubtedly there will be other examples that can come from the strategy. To find more examples, find a space or a class of spaces that are reliably CCC and then look for potential non-separable spaces among the dense subspaces of the starting space.

____________________________________________________________________

Exercises

- Show that in metrizable spaces, CCC and separable are equivalent. The only part that needs to be shown is that if

is metrizable and CCC, then

is separable.

- Show that any dense subspace of a CCC space is also CCC.

- Verify that the space

defined in Example 2 is dense in

and is not separable.

- Verify that the Pixley-Roy space

defined in Example 3 is CCC and not separable.

- Verify that function space

mentioned in Example 4 is not separable. Hint: use the pressing down lemma.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

- Steen, L. A., Seebach, J. A., Counterexamples in Topology, Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1995.

____________________________________________________________________

Revised October 26, 2018

Cp(X) where X is a separable metric space

Let be an uncountable cardinal. Let

be the Cartesian product of

many copies of the real line. This product space is not normal since it contains

as a closed subspace. However, there are dense subspaces of

are normal. For example, the

-product of

copies of the real line is normal, i.e., the subspace of

consisting of points which have at most countably many non-zero coordinates (see this post). In this post, we look for more normal spaces among the subspaces of

that are function spaces. In particular, we look at spaces of continuous real-valued functions defined on a separable metrizable space, i.e., the function space

where

is a separable metrizable space.

For definitions of basic open sets and other background information on the function space , see this previous post.

____________________________________________________________________

when

is a separable metric space

In the remainder of the post, denotes a separable metrizable space. Then,

is more than normal. The function space

has the following properties:

- normal,

- Lindelof (hence paracompact and collectionwise normal),

- hereditarily Lindelof (hence hereditarily normal),

- hereditarily separable,

- perfectly normal.

All such properties stem from the fact that has a countable network whenever

is a separable metrizable space.

Let be a topological space. A collection

of subsets of

is said to be a network for

if for each

and for each open

with

, there exists some

such that

. A countable network is a network that has only countably many elements. The property of having a countable network is a very strong property, e.g., having all the properties listed above. For a basic discussion of this property, see this previous post and this previous post.

To define a countable network for , let

be a countable base for the domain space

. For each

and for any open interval

in the real line with rational endpoints, consider the following set:

There are only countably many sets of the form . Let

be the collection of sets, each of which is the intersection of finitely many sets of the form

. Then

is a network for the function space

. To see this, let

where

is a basic open set in

where

is finite and each

is an open interval with rational endpoints. For each point

, choose

with

such that

. Clearly

. It follows that

.

Examples include ,

and

. All three can be considered subspaces of the product space

where

is the cardinality of the continuum. This is true for any separable metrizable

. Note that any separable metrizable

can be embedded in the product space

. The product space

has cardinality

. Thus the cardinality of any separable metrizable space

is at most continuum. So

is the subspace of a product space of

continuum many copies of the real lines, hence can be regarded as a subspace of

.

A space has countable extent if every closed and discrete subset of

is countable. The

-product

of the separable metric spaces

is a dense and normal subspace of the product space

. The normal space

has countable extent (hence collectionwise normal). The examples of

discussed here are Lindelof and hence have countable extent. Many, though not all, dense normal subspaces of products of separable metric spaces have countable extent. For a dense normal subspace of a product of separable metric spaces, one interesting problem is to find out whether it has countable extent.

____________________________________________________________________

Working with the function space Cp(X)

This post provides basic information about the space of real-valued continuous functions with the pointwise convergence topology. The goal is to discuss the setting and to define the standard basic open sets in the function space, providing background information for subsequent posts.

____________________________________________________________________

Completely Regular Spaces

The starting point is a completely regular space. A space is said to be completely regular if

is a

space and for each

and for each closed subset

of

with

, there is a continuous function

such that

and

. Note that the

axiom and the existence of the continuous function imply the

axiom, which is equivalent to the property that single points are closed sets. Completely regular spaces are also called Tychonoff spaces.

____________________________________________________________________

Defining the Function Space

Let be a completely regular space. Let

be the set of all real-valued continuous functions defined on the space

. The set

is naturally a subspace of the product space

. Thus

can be endowed with the subspace topology inherited from the product space

. When this is the case, the function space

is denoted by

. The topology on

is called the pointwise convergence topology.

Now we need a good handle on the open sets in the function space . A basic open set in the product space

is of the form

where each

is an open subset of

such that

for all but finitely many

(equivalently

for only finitely many

). Thus a basic open set in

is of the form:

where each is an open subset of

and

for all but finitely many

. In addition, when

, we can take

to be an open interval of the form

. To simplify notation, the basic open sets as described in (1) can also be notated by:

Thus when working with open sets in , we take

to mean the set of all

such that

for each

.

To make the basic open sets of more explicit, (1) or (1a) is translated as follows:

where is a finite set, for each

,

is an open interval of

, and

is the set of all

such that

.

There is another description of basic open sets that is useful. Let . Let

be finite. Let

. Let

be defined as follows:

In proving results about , we can use basic open sets that are described in any one of the three forms (1), (2) and (3). If

is a basic open subset of

, as described in (1) or (1a), we use

to denote the finite set of

such that

. The set

is called the support of

. The support for the basic open sets as described in (2) and (3) is already explicitly stated.

____________________________________________________________________

Basic Discussion

The theory of is a vast subject area. For a systematic introduction, see [1]. One fundamental theme in function space theory is the study of how properties of

and

are related. The domain space

and the function space

are not on the same footing. The domain

only has a topological structure. The function space

carries a topology and two natural algebraic operations of addition and multiplication, making it a topological ring. In addition,

can be regarded as a topological group, or a linear topological space. In this post and in many subsequent posts, we narrow the focus to the topological properties of

and

, paying attention to the how the topological properties of

and

are related.

In addition to the pointwise convergence topology, there are other topologies that can be defined on , e.g., the compact-open topology, the topology of uniform convergence and others. Both the pointwise convergence topology and the compact-open topology are examples of set-open topologies. In this post and in many of the subsequent posts, the focus is on the pointwise convergence topology, i.e., the subspace topology on

inherited from the product space.

The space automatically inherits certain properties of the product space

. Note that

is dense in

. The product

has the countable chain condition (CCC) since it is a product of separable spaces. Hence

always has the CCC, i.e., there are no uncountably many pairwise disjoint open subsets of

, regardless what the domain space

is. One consequence of the CCC is that

is paracompact if and only if

is Lindelof.

It is well known that is separable if and only if the cardinality of

continuum. Since

is dense in

,

is not separable if the cardinality of

continuum. Thus

is one way to get a CCC space that is not separable. There are non-separable

where the cardinality of

continuum. Obtaining such

would require more than the properties of the product space

; using properties of

would be necessary.

The properties of discussed so far are inherited from the product space. Refer to chapter one of [1] for other elementary properties of

. See this post for a discussion of

where

is a separable metric space. See this post about a consequence of normality of

.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

____________________________________________________________________

A factorization theorem for products of separable spaces

Let be a product space. Let

be a continuous function where

is a topological space. In this post, we discuss what it means for the continuous function

to depend on countably many coordinates and then discuss some conditions that we can impose on the product space and on the range space

to ensure that every continuous

defined on the product space will depend on countably many coordinates. This notion of a continuous function depending on countably many coordinates is equivalent to factoring the continuous function into the composition of a projection map and a continuous function defined on a countable subproduct (see Lemma 1 below).

Let’s set some notation about the product space we work with in this post. Let be a product space. Let

be a topological space. Let

be continuous. For any

,

is the natural projection from the full product space

into the subproduct

. Standard basic open sets of

are of the form

where each

is open in

and that

for all but finitely many

. We use

to denote the finite set of

where

.

____________________________________________________________________

Factoring a Continuous Map

The function is said to depend on countably many coordinates if there exists a countable set

such that for any

, if

for all

, then

. Suppose

is instead defined on a subspace

of

. The function

is said to depend on countably many coordinates if there exists a countable

such that for any

, if

for all

, then

.

We have the following lemmas.

Lemma 1

-

Let

- There exists a countable

such that for any

, if

for all

, then

.

- There exists a countable

such that

where

is continuous.

Lemma 1a

-

Let

- There exists a countable

such that for any

, if

for all

, then

.

- There exists a countable

such that

where

is continuous.

It is straightforward to verify Lemma 1 and Lemma 1a. We use condition 1 to define what it means for a function to be dependent on countably many coordinates. Both lemmas indicate that either condition is a valid definition. These two lemmas also indicate why the notion being discussed can be called a factorization notion.

____________________________________________________________________

When a Continuous Map Can Be Factored

We discuss some conditions that we can place on the product space and on the range space

so that any continuous map depends on countably many coordinates. We prove the following theorem.

Theorem 1

-

Let

Before stating the main theorem, we need one more lemma. Let . The set

is said to depend on countably many coordinates if there exists a countable

such that for any

and for any

, if

for all

, then

.

When we try to determine whether a function , where

, can be factored, we will need to decide whether a set

depends on countably many coordinates. Let

. The set

is said to depend on countably many coordinates if there exists a countable

such that for any

and for any

, if

for all

, then

. We have the following lemma.

Lemma 2

-

Let

- Let

be an open subset of

. Then

depends on countably many coordinates.

- Let

be an open subset of

. Then

depends on countably many coordinates (closure in

).

Proof of Lemma 2

Proof of Part 1

Let be open. Let

be a collection of pairwise disjoint open subsets of the open set

such that

is maximal with this property, i.e., if you throw one more open set into

, it will be no longer pairwise disjoint. Let

. Since

is maximal,

. Since

has the countable chain condition,

is countable.

Let . The set

is a countable subset of

since

is the union of countably many finite sets. We have the following claims.

Claim 1

The open set depends on the coordinates in

.

Let and

such that

for all

. We need to show that

. Firstly,

for some

. It follows that

for all

. Thus

. This completes the proof of Claim 1.

Claim 2

The set depends on the coordinates in

.

Let and

such that

for all

. We need to show

. To this end, let

be a standard basic open set with

. The goal is to find some

. Define

such that

for all

and

for all

. Then

. Since

, there exists some

. Define

such that

for all

and

for all

. Since

,

. On the other hand,

. This completes the proof of Claim 2.

As noted above, . Thus

depends on countably many coordinates, namely the coordinates in the set

. This completes the proof of Part 1.

Proof of Part 2

For any , let

denote the closure of

in

. Let

denote the closure of

in

. Let

be open. Let

be open in

such that

. By Part 1,

depends on countably many coordinates, say the coordinates in the countable set

. This means that for any

and for any

, if

for all

, then

. Thus for any

and for any

, if

for all

, then

. If we have

, then we are done. So we only need to show that if

and

, then

. This is why we need to assume

is dense in

.

Let and

. Let

be an open subset of

with

. There exists an open subset

of

such that

. Then

. Note that

is open and

. Since

is dense in

,

must contain points of

. These points of

are also points of

. Thus

contains points of

. It follows that

. This concludes the proof of Part 2.

Proof of Theorem 1

Let be a dense subspace of

. Let

be continuous. Let

be a countable base for the separable metrizable space

. By Lemma 2 Part 2, for each

,

depends on countably many coordinates, say the countable set

. Let

.

We claim that is a countable set of coordinates we need. Let

such that

for all

. We need to show that

. Suppose

. Choose

such that

for each

This is possible since is a second countable space. Then

for some

. Furthermore,

. Since

is continuous,

. Therefore,

. On the other hand,

depends on the countably many coordinates in

. We assume above that

for all

. Thus

for all

. This means that

, a contradiction. It must be that case that

.

____________________________________________________________________

Another Version

We state another version of Theorem 1 that will be useful in some situations.

Theorem 2

-

Let

- There exists a countable set

such that for any

, if

and

for all

, then

.

- There exists a countable set

and there exists a continuous

such that

.

The map is the projection map from

into the subproduct

defined by

. In Theorem 2, we only need to consider

being defined on the subspace

.

Theorem 2 follows from Theorem 1. It is only a matter of fitting Theorem 2 in the framework of Theorem 1. Note that the product is identical to the product

where

is a disjoint copy of the index set

. For

, let

be defined by

for all

and

for all

.

With the identification of with

, we have a setting that fits Theorem 1. The product

is also a product of separable spaces. The set

is a dense subspace of the product

. In this new setting, we view a point in

as

. The map

is still a continuous map. We can now apply Theorem 1.

Let be a countable set such that for all

, if

for all

, then

. Specifically, if

for all

and

for all

, then

.

Choose a countable set such that

and

. Here,

is the copy of

in

. We claim that

is a countable set we need in condition 1 of Theorem 2. Let

such that

and

for all

. This implies that

for all

and

for all

. Then

. Thus condition 1 of Theorem 2 holds. It is also straightforward to verify that Condition 1 and Condition 2 are equivalent.

____________________________________________________________________

Remarks

The notion of factorizing a continuous map defined on a product space is an old topic. Theorem 1 discussed in this post is based on Theorem 4 found in [6]. Theorem 4 found in [6] is to factor continuous maps defined on a product of separable spaces. Theorem 1 in this post is modified to consider continuous maps defined on a dense subspace of a product of separable spaces. This modification will make it more useful. The references listed below represent a small sample of papers or books that have involves theorems of factoring functions defined on products. The work in [3] and [5] have more systematic treatment.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Brandenburg H., Husek M., On mappings from products into developable spaces, Topology Appl., 26, 229-238, 1987.

- Engelking R., General Topology, Revised and Completed edition, Heldermann Verlag, Berlin, 1989.

- Engelking R., On functions defined on Cartesian products, Fund. Math., 59, 221-231, 1966.

- Keesling J., Normality and infinite product spaces, Adv. in. Math., 9, 90-92, 1972.

- Noble N., Ulmer M., Factoring functions on Cartesian products, Trans. Amer. Math. Soc., 163, 329-339, 1972.

- Ross K. A., Stone A. H., Products of separable spaces, Amer. Math. Monthly, 71, 398-403, 1964.

____________________________________________________________________

A lemma dealing with normality in products of separable metric spaces

In this post we prove a lemma that is a great tool for working with product spaces of separable metrizable spaces. As an application of the lemma, we give an alternative proof for showing the non-normality of the product space of uncountably many copies of the discrete space of the non-negative integers.

Consider the product space where each

is a separable and metrizable space. The lemma we discuss here is a tool that can shed some light on normality of dense subspaces of the product space

. The lemma is stated in two equivalent forms (Lemma 1 and Lemma 2).

Before stating the lemmas, let’s fix some notations. For any , the map

is the natural projection from the full product

to the subproduct

. The standard basic open sets in the product space

are of the form

where

for all but finitely many

. We use

to denote the set of finitely many

such that

.

Given a space , and given

, the sets

and

are separated if

.

Lemma 1

-

Let

- There exist disjoint open subsets

and

of

such that

and

.

- There exists a countable

such that the sets

and

are separated in the space

.

Lemma 2

-

Let

If Lemma 1 holds, it is clear that Lemma 2 holds. We prove Lemma 1. The lemmas indicate that to separate disjoint sets in the full product, it suffices to separate in a countable subproduct. In this sense normality in dense subspaces of a product of separable metrizable spaces only depends on countably many coordinates.

This lemma seems to have been around for a long time. We cannot find any reference of this lemma in Engelking’s topology textbook (see [4]). We found three references. One is Corson’s paper (see [3]), in which the lemma is mentioned in relation to the non-normality of and is attributed to a paper of M. Bockstein in 1948. Another is a paper of Baturov (see [2]), in which the lemma is used to prove a theorem about normality in dense subspace of

where

is a separable metric space. In [2] the lemma is attributed to Uspenskii. Another reference is Arkhangelskii’s book on function space (see Lemma I.6.1 on p. 43 in [1]) where the lemma is used in proving some facts about normality in function spaces

.

____________________________________________________________________

Proof of Lemma 1

Let and

be disjoint open subsets of

with

and

. Let

and

be open subsets of

such that

and

. Since

is dense in

,

.

Let be a maximal pairwise disjoint collection of standard basic open sets, each of which is a subset of

. Let

be a maximal pairwise disjoint collection of standard basic open sets, each of which is a subset of

. These two collections can be obtained using a Zorn lemma argument. The product space

has the countable chain condition since it is a product of separable spaces. So both

and

are countable. Let

be the union of finite sets each one of which is a

where

. The set

is countable too.

Let and

. Note that

. We have the following observations:

The above observations lead to the following observations:

implying that . Both

and

are open subsets of

and are dense in

, respectively.

We claim that . Suppose that

. Then

contains a point of

, say

. With

,

for some

where

. Note that

. Thus

. On the other hand,

implies that

for some

. It follows that

, a contradiction. Therefore

.

We have and

. This implies that

and

(closure in

). Then

and

are separated in

as well. This concludes the proof for the

direction.

Suppose that is countable such that

and

are separated in the space

. Note that

and

. Then we have the following:

Consider . The space

is an open subspace of

. Furthermore,

is a subspace of

, which is a separable and metrizable space. Thus the space

is metrizable and hence normal.

For , let

denote the closure of

in the space

. Note that

and

are disjoint and closed sets in

. Let

and

be disjoint open subsets of

such that

and

. Then

and

are disjoint open subsets of

such that

and

.

____________________________________________________________________

Remark

The proof of Lemma 1 does not need the full strength of separable metric in each factor of the product space. The above proof only makes two assumptions about the product space: the product space has the countable chain condition (CCC) and that any countable subproduct is normal, i.e.,

is normal for any countable

.

____________________________________________________________________

Example

As an application of the above lemma, we give another proof of the non-normality of the product space of uncountably many copies of the discrete space of the non-negative integers. See this post for a version of A. H. Stone’s original proof.

Let be the set of all nonnegative integers and let

be the first uncountable ordinal (i.e. the set of all countable ordinals). We provide an alternative proof that

is not normal. In A. H. Stone’s proof, the following disjoint closed sets cannot be separated in

:

We can also use Lemma 1 to show that and

cannot be separated. Note that for each countable

, the sets

and

have non-empty intersection. Hence they cannot be separated in

. By Lemma 1,

and

cannot be separated in the full product space

.

To see that , choose a function

such that

. Let

be defined by

for all

. Then

.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

- Baturov, D. P., Normality in dense subspaces of products, Topology Appl., 36, 111-116, 1990.

- Corson, H. H., Normality in subsets of product spaces, Amer. J. Math., 81, 785-796, 1959.

- Engelking, R., General Topology, Revised and Completed edition, Heldermann Verlag, Berlin, 1989.

____________________________________________________________________

Looking for a closed and discrete subspace of a product space

I had long suspected that there probably is an uncountable closed and discrete subset of the product space of uncountably many copies of the real line. Then I found the statement in the Encyclopedia of General Topology (page 76 in [3]) that “for every infinite cardinal , the product

includes

as a closed subspace” where

is the discrete space of cardinality of

. When

(the first infinite cardinal), there is a closed and discrete subset of cardinality

in the product space

(the product space of continuum many copies of a countable discrete space). Despite the fact that this product space is a separable space, a closed and discrete set of cardinality continuum is hiding in the product space

. What is more amazing is that this result gives us a glimpse into the working of the product topology with uncountably many factors. There are easily defined discrete subspaces of

. But these discrete subspaces are not closed in the product space, making the result indicated here a remarkable one.

The Encyclopedia of General Topology points to two references [2] and [4]. I could not find these papers online. It turns out that Engelking, the author of [2], included this fact as an exercise in his general topology textbook (see Exercise 3.1.H (a) in [1]). This post presents a proof of this fact based on the hints that are given in [1]. To make the argument easier to follow, the proof uses some of the hints in a slightly different form.

____________________________________________________________________

The Exercise

Let be the closed unit interval. Let

be the unit interval with the discrete topology. Let

be the set of all nonnegative integers with the discrete topology. Let

where each

. We can also denote

by

. The problem is to show that the discrete space

can be embedded as a closed and discrete subspace of

.

____________________________________________________________________

A Solution

For each , choose a sequence

of open intervals (in the usual topology of

) such that

for each

,

for each

(the closure is in the usual topology of

),

.

For any , we can make

open intervals of the form

. For

,

have the form

. For

,

have the form

.

The above sequences of open intervals help define a homeomorphic embedding of the discrete space into the product

. For each

, define the function

by letting:

for each . We now define the embedding

by letting:

for each . For each point

,

is the point in the product space such that the

coordinate of

is the value of the function

evaluated at

. Let

.

The mapping is an evaluation map (called diagonal map in [1]). It is a homeomorphism if the following three conditions are met:

- If each

is continuous, then

is continuous.

- If the family of functions

separates points in

, then

is injective (i.e. a one-to-one function).

- If

separates points from closed sets in

, then the inverse

is also continuous.

The first point is easily seen. Note that both the domain and the range of have the discrete topology. Thus these functions are continuous. To see the second point, let

with

. Note that

while

.

Since is discrete, any subset of

is closed. To see the third point, let

and

. Once again,

while

for all

. Clearly

(closure in the discrete space

). Thus

is also continuous. For more details about why

is an embedding, see the previous post called The Evaluation Map.

Let . Since

is a homeomorphism,

is a discrete subspace of the product space

. We only need to show

is closed in

. Let

such that

. We show that there is an open neighborhood of

that misses the set

. There are two cases to consider. One is that

for all

. The other is that

for some

. The first case is more involved.

Case 1

Suppose that for all

. First define a local base

of the point

. Let

be finite and let

be defined by:

Let be the set of all possible

. For an arbitrary

, consider

. By definition,

. To make the argument below easier to see, let’s further describe

.

The last description above indicates that if and if

, then

. To wrap up Case 1, we would like to produce one particular

. Consider the open cover

of

. Since

is compact in the usual topology, there is a finite

such that

. This means that for this particular finite set

,

. Putting it in another way, the open neighborhood

of

contains no point of

. The proof for Case 1 is completed.

Case 2

Suppose that for some

. Since

, in particular

. So for some

,

. Now define the following open set containing

.

Note that since

. Furthermore, for each

,

since

. Thus

is an open neighborhood of

containing no point of

. The proof for Case 2 is completed.

We have shown that the image of the discrete space under the homeomorphism

is closed in the product space

.

____________________________________________________________________

Comments

The preceding proof shows that the product space of continuum many copies of contains a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum. This is a remarkable result. At a glance, it is not entirely clear that a closed and discrete set of this large size can be found in the product space in question.

One immediate consequence is that the product space is not normal since it is a separable space. By Jones’ lemma, any separable normal space cannot have a closed and discrete subset of cardinality continuum. However, if the goal is only to show non-normality, we only need to show that

is not normal (a proof is found in this post). Thus the value of the preceding proof is to demonstrate how to produce a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum in the product space in question.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Engelking, R., General Topology, Revised and Completed edition, Heldermann Verlag, Berlin, 1989.

- Engelking, R., On the double circumference of Alexandroff, Bull. Acad. Polon. Sci., 16, 629-634, 1968.

- Hart, K. P., Nagata J. I., Vaughan, J. E., editors, Encyclopedia of General Topology, First Edition, Elsevier Science Publishers B. V, Amsterdam, 2003.

- Juhasz, I., On closed discrete subspace of product spaces, Bull. Acad. Polon. Sci., 17, 219-223, 1969.

____________________________________________________________________

A theorem about CCC spaces

It is a well known result in general topology that in any regular space with the countable chain condition, paracompactness and the Lindelof property are equivalent. The proof of this result hinges on one theorem about the spaces with the countable chain condition. In this post we are to put the spotlight on this theorem (Theorem 1 below) and then use it to prove a few results. These results indicate that in a space with the countable chain condition with some weaker covering property is either Lindelof or paracompact.

This post is centered on a theorem about the CCC property (Theorem 1 and Theorem 1a below). So it can be considered as a continuation of a previous post on CCC called Some basic properties of spaces with countable chain condition. The results that are derived from Theorem 1 are also found in [2]. But the theorem concerning CCC is only a small part of that paper among several other focuses. In this post, the exposition is to explain several interesting theorems that are derived from Theorem 1. One of the theorems is the statement that every locally compact metacompact perfectly normal space is paracompact, a theorem originally proved by Arhangelskii (see Theorem 11 below).

____________________________________________________________________

CCC Spaces

All spaces under consideration are at least and regular. A space

is said to have the countable chain condition (to have the CCC for short) if

is a disjoint collection of non-empty open subsets of

(meaning that for any

with

, we have

), then

is countable. In other words, in a space with the CCC, there cannot be uncountably many pairwise disjoint non-empty open sets. For ease of making a statement or stating a result, if

has the CCC, we also say that

is a CCC space or

is CCC.

____________________________________________________________________

A Theorem about CCC Spaces

The theorem of CCC spaces we want to discuss has to do with collections of open sets that are “nice”. We first define what we mean by nice. Let be a collection of non-empty subsets of the space

. The collection

is said to be point-finite (point-countable) if each point of

belongs to only finitely (countably) many sets in

.

Now we define what we mean by “nice” collection of open sets. The collection is said to be locally finite (locally countable) at a point

if there exists an open set

with

such that

meets at most finitely (countably) many sets in

. The collection

is said to be locally finite (locally countable) if it is locally finite (locally countable) at each

.

The property of being a separable space implies the CCC. The reverse is not true. However the CCC property is still a very strong property. The CCC property is equivalent to the property that if a collection of non-empty open sets is “nice” on a dense set of points, then the collection of open sets is a countable collection. The following is a precise statement.

-

Theorem 1

-

Let

is dense in the open subspace , then

must be countable.

The collections of open sets in the above theorem do not have to be open covers. However, if they are open covers, the theorem can tie CCC spaces with some covering properties. As long as the space has the CCC, any open cover that is locally-countable on a dense set must be countable. Looking at it in the contrapositive angle, in a CCC space, any uncountable open cover is not locally-countable in some open set.

Proof of Theorem 1

Let be a collection of open subsets of

such that the set

as defined above is dense in the open subspace

. We show that

is countable. Suppose not.

For each , since

, we can choose a non-empty open set

such that

has non-empty intersection with only countably many sets in

. Let

be the following collection:

For , by a chain from

to

, we mean a finite collection

such that ,

and

for any

. For each open set

, define

and

as follows:

One observation we make is that for , if

, then

and

. So the distinct

are pairwise disjoint. Because the space

has the CCC, there can be only countably many distinct open sets

. Thus there can be only countably many distinct collections

.

Note that each is a countable collection of open sets. Each

meets only countably many open sets in

. So each

can meet only countably many sets in

, since for each

,

for some

. Thus for each

, in considering all finite-length chain starting from

, there can be only countably many open sets in

that can be linked to

. Thus

must be countable. In taking the union of all

, we get back the collection

. Thus we have:

Because the space is CCC, there are only countably many distinct collections

in the above union. Each

is countable. So

is a countable collection of open sets.

Furthermore, each contains at least one set in

. From the way we choose sets in

, we see that for each

,

for at most countably many

. The argument indicates that we have a one-to-countable mapping from

to

. Thus the original collection

must be countable.

The property in Theorem 1 is actually equivalent to the CCC property. Just that the proof of Theorem 1 represents the hard direction that needs to be proved. Theorem 1 can be expanded to be the following theorem.

-

Theorem 1a

- The space

has the CCC.

- If

is a collection of non-empty open subsets of

such that the following set

is dense in the open subspace

, then

must be countable.

- If

is a collection of non-empty open subsets of

such that

is locally-countable at every point in the open subspace

, then

must be countable.

-

Let

The direction has been proved above. The directions

and

are straightforward.

____________________________________________________________________

Tying Theorem 1 to “Nice” Open Covers

One easy application of Theorem 1 is to tie it to locally-finite and locally-countable open covers. We have the following theorem.

-

Theorem 2

-

In any CCC space, any locally-countable open cover must be countable. Thus any locally-finite open cover must also be countable.

Theorem 2 gives the well known result that any CCC paracompact space is Lindelof (see Theorem 5 below). In fact, Theorem 2 gives the result that any CCC para-Lindelof space is Lindelof (see Theorem 6 below). A space is para-Lindelof if every open cover has a locally-countable open refinement.

Can Theorem 2 hold for point-finite covers (or point-countable covers)? The answer is no (see Example 1 below). With the additional property of having a Baire space, we have the following theorem.

-

Theorem 3

-

In any Baire space with the CCC, any point-finite open cover must be countable.

A Space is a Baire space if

are dense open subsets of

, then

. For more information about Baire spaces, see this previous post.

.

Proof of Theorem 3

Let be a Baire space with the CCC. Let

be a point-finite open cover of

. Suppose that

is uncountable. We show that this assumption with lead to a contradiction. Thus

must be countable.

By Theorem 1, there exists an open set such that

is not locally-countable at any point in

. For each positive integer

, let

be the following:

Note that . Furthermore, each

is a closed set in the space

. Since

is a Baire space, every non-empty open subset of

is of second category (i.e. it cannot be a union of countably many closed and nowhere dense sets). Thus it cannot be that each

is nowhere dense in

. For some

,

is not nowhere dense. There must exist some open

such that

is dense in

. Because

is closed,

.

Choose . The point

is in at most

open sets in

. Let

such that

. Clearly

. Let

. Note that

.

Every point in belongs to at most

many sets in

and already belong to

sets in

. So each point in

can belong to at most

additional open sets in

. Consider the case

and the case

. We show that each case leads to a contradiction.

Suppose that . Then each point of

can only meet

open sets in

, namely

. This contradicts that

is not locally-countable at points in

.

Suppose that . Let

. Let

be the following collection:

Each element of is an open subset of

that is the intersection of exactly

many open sets in

. So

is a collection of pairwise disjoint open sets. The open set

as a topological space has the CCC. So

is at most countable. Thus the open set

meets at most countably many open sets in

, contradicting that

is not locally-countable at points in

.

Both cases and

lead to contradiction. So

must be countable. The proof to Theorem 3 is completed.

As a corollary to Theorem 3, we have the result that every Baire CCC metacompact space is Lindelof.

____________________________________________________________________

Some Applications of Theorems 2 and 3

In proving paracompactness in some of the theorems, we need a theorem involving the concept of star-countable open cover. A collection of subsets of a space

is said to be star-finite (star-countable) if for each

, only finitely (countably) many sets in

meets

, i.e., the following set

is finite (countable). The proof of the following theorem can be found in Engleking (see the direction (iv) implies (i) in the proof of Theorem 5.3.10 on page 326 in [1]).

-

Theorem 4

-

If every open cover of a regular space

As indicated in the above section, Theorem 2 and Theorem 3 have some obvious applications. We have the following theorems.

-

Theorem 5

-

Let

Proof of Theorem 5

The direction follows from the fact that any regular Lindelof space is paracompact.

The direction follows from Theorem 2.

-

Theorem 6

-

Every CCC para-Lindelof space is Lindelof.

Proof of Theorem 6

This also follows from Theorem 2.

-

Theorem 7

-

Every Baire CCC metacompact space is Lindelof.

Proof of Theorem 7

Let be a Baire CCC metacompact space. Let

be an open cover of

. By metacompactness, let

be a point-finite open refinement of

. By Theorem 3,

must be countable.

-

Theorem 8

-

Every Baire CCC hereditarily metacompact space is hereditarily Lindelof.

Proof of Theorem 8

Let be a Baire CCC hereditarily metacompact space. To show that

is hereditarily Lindelof, it suffices to show that every non-empty open subset is Lindelof. Let

be open. Then

has the CCC and is also metacompact. Being a Baire space is hereditary with respect to open subspaces. So

is a Baire space too. By Theorem 7,

is Lindelof.

-

Theorem 9

-

Every locally CCC regular para-Lindelof space is paracompact.

Proof of Theorem 9

A space is locally CCC if every point has an open neighborhood that has the CCC. Let be a regular space that is locally CCC and para-Lindelof. Let

be an open cover of

. Using the locally CCC assumption and by taking a refinement of

if necessary, we can assume that each open set in

has the CCC. By the para-Lindelof assumption, let

be a locally-countable open refinement of

. So each open set in

has the CCC too.

Now we show that is star-countable. Let

. Let

be the following collection:

which is is open cover of . Within the subspace

,

is a locally-countable open cover. By Theorem 2,

must be countable. The collection

represents all the open sets in

that have non-empty intersection with

. Thus only countably many open sets in

can meet

. So

is a star-countable open refinement of

. By Theorem 4,

is paracompact.

-

Theorem 10

-

Every locally CCC regular metacompact Baire space is paracompact.

Proof of Theorem 10

Let be a regular space that is locally CCC and is a metacompact Baire space. Let

be an open cover of

. Using the locally CCC assumption and by taking a refinement of

if necessary, we can assume that each open set in

has the CCC. By the metacompact assumption, let

be a point-finite open refinement of

. So each open set in

has the CCC too. Each open set in

is also a Baire space.

Now we show that is star-countable. Let

. Let

be the following collection:

which is is open cover of . Within the subspace

,

is a point-finite open cover. By Theorem 3,

must be countable. The collection

represents all the open sets in

that have non-empty intersection with

. Thus only countably many open sets in

can meet

. So

is a star-countable open refinement of

. By Theorem 4,

is paracompact.

-

Theorem 11

-

Every locally compact metacompact perfectly normal space is paracompact.

Proof of Theorem 11

This follows from Theorem 10 after we prove the following two points:

- Any locally compact space is a Baire space.

- Any perfect locally compact space is locally CCC.

To see the first point, let be a locally compact space. Let

be dense open sets in

. Let

and let

be open such that

and

is compact. We show that

contains a point that belongs to all

. Let

, which is open and non-empty. Next choose non-empty open

such that

and

. Next choose non-empty open

such that

and

. Continue in this manner, we have a sequence of open sets

such that for each

,

and

is compact. The intersection of all the

is non-empty. The points in the intersection must belong to each

.

To see the second point, let be a locally compact space such that every closed set is a

-set. Suppose that

is not locally CCC at

. Let

be open such that

and

is compact. Then

must not have the CCC. Let

be a pairwise disjoint collection of open subsets of

. Let

and let

.

Let where each

is open in

and

for each integer

. For each

, pick

. For each

, there is some integer

such that

. So there must exist some integer

such that

is uncountable.

The set is an infinite subset of the compact set

. So

has a limit point, say

(also called cluster point). Clearly

. So

. In particular,

. Then

contains some points of

. But for any

,

, a contradiction. So

must be locally CCC at each

.

____________________________________________________________________

Some Examples

Example 1

A CCC space with an uncountable point-finite open covers. This example demonstrates that in Theorem 2, locally-finite or locally-countable cannot be replaced by point-finite. Consider the following product space:

i.e, the product space of many copies of the two-point discrete space

. Let

be the set of all points

such that

for only finitely many

.

The product space is the product of separable spaces, hence has the CCC. The space

is dense in

. Hence

has the CCC. For each

, define

as follows:

Then is a point-finite open cover of

. Of course,

in this example is not a Baire space.

The following three examples center around the four properties in Theorem 7 (Baire + CCC + metacompact imply Lindelof). These examples show that each property in the hypothesis is crucial.

Example 2

A separable non-Lindelof space that is a Baire space. This example shows that the metacompact assumption is crucial for Theorem 7.

The example is the Sorgenfrey plane where

is the real line with the Sorgenfrey topology (generated by the half-open intervals of the form

). It is well known that

is not Lindelof. The Sorgenfrey plane is Baire and is separable (hence CCC). Furthermore,

is not metacompact (if it were, it would be Lindelof by Theorem 7).

Example 3

A non-Lindelof metacompact Baire space . This example shows that the CCC assumption in Theorem 7 is necessary.

This space is the subspace of Bing’s Example G that has finite support (defined and discussed in the post A subspace of Bing’s example G. It is normal and not collectionwise normal (hence cannot be Lindelof) and metacompact. The space

does not have CCC since it has uncountably many isolated points. Any space with a dense set of isolated points is a Baire space. Thus the space

is also a Baire space.

Example 4

A non-Lindelof CCC metacompact non-Baire space . This example shows that the Baire space assumption in Theorem 7 is necessary.

Let be the set of all non-empty finite subsets of the real line with the Pixley-Roy topology. Note that

is non-Lindelof and has the CCC and is metacompact. Of course it is not Baire. For more information on Pixley-Roy spaces, see the post called Pixley-Roy hyperspaces. For the purpose of this example, the Pixley-Roy space can be built on any uncountable separable metrizable space.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Engelking, R., General Topology, Revised and Completed edition, Heldermann Verlag, Berlin, 1989.

- Tall, F. D., The Countable Chain Condition Versus Separability – Applications of Martin’s Axiom, Gen. Top. Appl., 4, 315-339, 1974.

____________________________________________________________________

Pixley-Roy hyperspaces

In this post, we introduce a class of hyperspaces called Pixley-Roy spaces. This is a well-known and well studied set of topological spaces. Our goal here is not to be comprehensive but rather to present some selected basic results to give a sense of what Pixley-Roy spaces are like.

A hyperspace refers to a space in which the points are subsets of a given “ground” space. There are more than one way to define a hyperspace. Pixley-Roy spaces were first described by Carl Pixley and Prabir Roy in 1969 (see [5]). In such a space, the points are the non-empty finite subsets of a given ground space. More precisely, let be a

space (i.e. finite sets are closed). Let

be the set of all non-empty finite subsets of

. For each

and for each open subset

of

with

, we define:

The sets over all possible

and

form a base for a topology on

. This topology is called the Pixley-Roy topology (or Pixley-Roy hyperspace topology). The set

with this topology is called a Pixley-Roy space.