In this post, we introduce a class of hyperspaces called Pixley-Roy spaces. This is a well-known and well studied set of topological spaces. Our goal here is not to be comprehensive but rather to present some selected basic results to give a sense of what Pixley-Roy spaces are like.

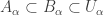

A hyperspace refers to a space in which the points are subsets of a given “ground” space. There are more than one way to define a hyperspace. Pixley-Roy spaces were first described by Carl Pixley and Prabir Roy in 1969 (see [5]). In such a space, the points are the non-empty finite subsets of a given ground space. More precisely, let  be a

be a  space (i.e. finite sets are closed). Let

space (i.e. finite sets are closed). Let ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) be the set of all non-empty finite subsets of

be the set of all non-empty finite subsets of  . For each

. For each ![F \in \mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=F+%5Cin+%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and for each open subset

and for each open subset  of

of  with

with  , we define:

, we define:

The sets ![[F,U]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BF%2CU%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) over all possible

over all possible  and

and  form a base for a topology on

form a base for a topology on ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . This topology is called the Pixley-Roy topology (or Pixley-Roy hyperspace topology). The set

. This topology is called the Pixley-Roy topology (or Pixley-Roy hyperspace topology). The set ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) with this topology is called a Pixley-Roy space.

with this topology is called a Pixley-Roy space.

The hyperspace as defined above was first defined by Pixley and Roy on the real line (see [5]) and was later generalized by van Douwen (see [7]). These spaces are easy to define and is useful for constructing various kinds of counterexamples. Pixley-Roy played an important part in answering the normal Moore space conjecture. Pixley-Roy spaces have also been studied in their own right. Over the years, many authors have investigated when the Pixley-Roy spaces are metrizable, normal, collectionwise Hausdorff, CCC and homogeneous. For a small sample of such investigations, see the references listed at the end of the post. Our goal here is not to discuss the results in these references. Instead, we discuss some basic properties of Pixley-Roy to solidify the definition as well as to give a sense of what these spaces are like. Good survey articles of Pixley-Roy are [3] and [7].

____________________________________________________________________

Basic Discussion

In this section, we focus on properties that are always possessed by a Pixley-Roy space given that the ground space is at least  . Let

. Let  be a

be a  space. We discuss the following points:

space. We discuss the following points:

- The topology defined above is a legitimate one, i.e., the sets

![[F,U]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BF%2CU%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) indeed form a base for a topology on

indeed form a base for a topology on ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a Hausdorff space.

is a Hausdorff space.![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a zero-dimensional space.

is a zero-dimensional space.![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a completely regular space.

is a completely regular space.![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a hereditarily metacompact space.

is a hereditarily metacompact space.

Let ![\mathcal{B}=\left\{[F,U]: F \in \mathcal{F}[X] \text{ and } U \text{ is open in } X \right\}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BB%7D%3D%5Cleft%5C%7B%5BF%2CU%5D%3A+F+%5Cin+%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D+%5Ctext%7B+and+%7D+U+%5Ctext%7B+is+open+in+%7D+X+%5Cright%5C%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Note that every finite set

. Note that every finite set  belongs to at least one set in

belongs to at least one set in  , namely

, namely ![[F,X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BF%2CX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . So

. So  is a cover of

is a cover of ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . For

. For ![A \in [F_1,U_1] \cap [F_2,U_2]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=A+%5Cin+%5BF_1%2CU_1%5D+%5Ccap+%5BF_2%2CU_2%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) , we have

, we have ![A \in [A,U_1 \cap U_2] \subset [F_1,U_1] \cap [F_2,U_2]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=A+%5Cin+%5BA%2CU_1+%5Ccap+U_2%5D+%5Csubset+++%5BF_1%2CU_1%5D+%5Ccap+%5BF_2%2CU_2%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . So

. So  is indeed a base for a topology on

is indeed a base for a topology on ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

To show ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is Hausdorff, let

is Hausdorff, let  and

and  be finite subsets of

be finite subsets of  where

where  . Then one of the two sets has a point that is not in the other one. Assume we have

. Then one of the two sets has a point that is not in the other one. Assume we have  . Since

. Since  is

is  , we can find open sets

, we can find open sets  such that

such that  ,

,  and

and  . Then

. Then ![[A,U \cup V]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BA%2CU+%5Ccup+V%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and

and ![[B,V]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BB%2CV%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) are disjoint open sets containing

are disjoint open sets containing  and

and  respectively.

respectively.

To see that ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a zero-dimensional space, we show that

is a zero-dimensional space, we show that  is a base consisting of closed and open sets. To see that

is a base consisting of closed and open sets. To see that ![[F,U]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BF%2CU%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is closed, let

is closed, let ![C \notin [F,U]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=C+%5Cnotin+%5BF%2CU%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Either

. Either  or

or  . In either case, we can choose open

. In either case, we can choose open  with

with  such that

such that ![[C,V] \cap [F,U]=\varnothing](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BC%2CV%5D+%5Ccap+%5BF%2CU%5D%3D%5Cvarnothing&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

The fact that ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is completely regular follows from the fact that it is zero-dimensional.

is completely regular follows from the fact that it is zero-dimensional.

To show that ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is metacompact, let

is metacompact, let  be an open cover of

be an open cover of ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . For each

. For each ![F \in \mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=F+%5Cin+%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) , choose

, choose  such that

such that  and let

and let ![V_F=[F,X] \cap G_F](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=V_F%3D%5BF%2CX%5D+%5Ccap+G_F&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Then

. Then ![\mathcal{V}=\left\{V_F: F \in \mathcal{F}[X] \right\}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BV%7D%3D%5Cleft%5C%7BV_F%3A+F+%5Cin+%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D+%5Cright%5C%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a point-finite open refinement of

is a point-finite open refinement of  . For each

. For each ![A \in \mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=A+%5Cin+%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) ,

,  can only possibly belong to

can only possibly belong to  for the finitely many

for the finitely many  .

.

A similar argument show that ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is hereditarily metacompact. Let

is hereditarily metacompact. Let ![Y \subset \mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=Y+%5Csubset+%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Let

. Let  be an open cover of

be an open cover of  . For each

. For each  , choose

, choose  such that

such that  and let

and let ![W_F=([F,X] \cap Y) \cap H_F](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=W_F%3D%28%5BF%2CX%5D+%5Ccap+Y%29+%5Ccap+H_F&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Then

. Then  is a point-finite open refinement of

is a point-finite open refinement of  . For each

. For each  ,

,  can only possibly belong to

can only possibly belong to  for the finitely many

for the finitely many  such that

such that  .

.

____________________________________________________________________

More Basic Results

We now discuss various basic topological properties of ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . We first note that

. We first note that ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a discrete space if and only if the ground space

is a discrete space if and only if the ground space  is discrete. Though we do not need to make this explicit, it makes sense to focus on non-discrete spaces

is discrete. Though we do not need to make this explicit, it makes sense to focus on non-discrete spaces  when we look at topological properties of

when we look at topological properties of ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . We discuss the following points:

. We discuss the following points:

- If

is uncountable, then

is uncountable, then ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is not separable.

is not separable.

- If

is uncountable, then every uncountable subspace of

is uncountable, then every uncountable subspace of ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is not separable.

is not separable.

- If

![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is Lindelof, then

is Lindelof, then  is countable.

is countable.

- If

![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is Baire space, then

is Baire space, then  is discrete.

is discrete.

- If

![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has the CCC, then

has the CCC, then  has the CCC.

has the CCC.

- If

![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has the CCC, then

has the CCC, then  has no uncountable discrete subspaces,i.e.,

has no uncountable discrete subspaces,i.e.,  has countable spread, which of course implies CCC.

has countable spread, which of course implies CCC.

- If

![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has the CCC, then

has the CCC, then  is hereditarily Lindelof.

is hereditarily Lindelof.

- If

![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has the CCC, then

has the CCC, then  is hereditarily separable.

is hereditarily separable.

- If

has a countable network, then

has a countable network, then ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has the CCC.

has the CCC.

- The Pixley-Roy space of the Sorgenfrey line does not have the CCC.

- If

is a first countable space, then

is a first countable space, then ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a Moore space.

is a Moore space.

Bullet points 6 to 9 refer to properties that are never possessed by Pixley-Roy spaces except in trivial cases. Bullet points 6 to 8 indicate that ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) can never be separable and Lindelof as long as the ground space

can never be separable and Lindelof as long as the ground space  is uncountable. Note that

is uncountable. Note that ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is discrete if and only if

is discrete if and only if  is discrete. Bullet point 9 indicates that any non-discrete

is discrete. Bullet point 9 indicates that any non-discrete ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) can never be a Baire space. Bullet points 10 to 13 give some necessary conditions for

can never be a Baire space. Bullet points 10 to 13 give some necessary conditions for ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) to be CCC. Bullet 14 gives a sufficient condition for

to be CCC. Bullet 14 gives a sufficient condition for ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) to have the CCC. Bullet 15 indicates that the hereditary separability and the hereditary Lindelof property are not sufficient conditions for the CCC of Pixley-Roy space (though they are necessary conditions). Bullet 16 indicates that the first countability of the ground space is a strong condition, making

to have the CCC. Bullet 15 indicates that the hereditary separability and the hereditary Lindelof property are not sufficient conditions for the CCC of Pixley-Roy space (though they are necessary conditions). Bullet 16 indicates that the first countability of the ground space is a strong condition, making ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) a Moore space.

a Moore space.

__________________________________

To see bullet point 6, let  be an uncountable space. Let

be an uncountable space. Let  be any countable subset of

be any countable subset of ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Choose a point

. Choose a point  that is not in any

that is not in any  . Then none of the sets

. Then none of the sets  belongs to the basic open set

belongs to the basic open set ![[\left\{x \right\} ,X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Cleft%5C%7Bx+%5Cright%5C%7D+%2CX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Thus

. Thus ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) can never be separable if

can never be separable if  is uncountable.

is uncountable.

__________________________________

To see bullet point 7, let ![Y \subset \mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=Y+%5Csubset+%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) be uncountable. Let

be uncountable. Let  . Let

. Let  be any countable subset of

be any countable subset of  . We can choose a point

. We can choose a point  that is not in any

that is not in any  . Choose some

. Choose some  such that

such that  . Then none of the sets

. Then none of the sets  belongs to the open set

belongs to the open set ![[A ,X] \cap Y](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BA+%2CX%5D+%5Ccap+Y&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . So not only

. So not only ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is not separable, no uncountable subset of

is not separable, no uncountable subset of ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is separable if

is separable if  is uncountable.

is uncountable.

__________________________________

To see bullet point 8, note that ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has no countable open cover consisting of basic open sets, assuming that

has no countable open cover consisting of basic open sets, assuming that  is uncountable. Consider the open collection

is uncountable. Consider the open collection ![\left\{[F_1,U_1],[F_2,U_2],[F_3,U_3],\cdots \right\}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5C%7B%5BF_1%2CU_1%5D%2C%5BF_2%2CU_2%5D%2C%5BF_3%2CU_3%5D%2C%5Ccdots+%5Cright%5C%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Choose

. Choose  that is not in any of the sets

that is not in any of the sets  . Then

. Then  cannot belong to

cannot belong to ![[F_n,U_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BF_n%2CU_n%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) for any

for any  . Thus

. Thus ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) can never be Lindelof if

can never be Lindelof if  is uncountable.

is uncountable.

__________________________________

For an elementary discussion on Baire spaces, see this previous post.

To see bullet point 9, let  be a non-discrete space. To show

be a non-discrete space. To show ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is not Baire, we produce an open subset that is of first category (i.e. the union of countably many closed nowhere dense sets). Let

is not Baire, we produce an open subset that is of first category (i.e. the union of countably many closed nowhere dense sets). Let  a limit point (i.e. an non-isolated point). We claim that the basic open set

a limit point (i.e. an non-isolated point). We claim that the basic open set ![V=[\left\{ x \right\},X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=V%3D%5B%5Cleft%5C%7B+x+%5Cright%5C%7D%2CX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a desired open set. Note that

is a desired open set. Note that  where

where

We show that each  is closed and nowhere dense in the open subspace

is closed and nowhere dense in the open subspace  . To see that it is closed, let

. To see that it is closed, let  with

with  . We have

. We have  . Then

. Then ![[A,X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BA%2CX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is open and every point of

is open and every point of ![[A,X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BA%2CX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has more than

has more than  points of the space

points of the space  . To see that

. To see that  is nowhere dense in

is nowhere dense in  , let

, let ![[B,U]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BB%2CU%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) be open with

be open with ![[B,U] \subset V](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BB%2CU%5D+%5Csubset+V&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . It is clear that

. It is clear that  where

where  is open in the ground space

is open in the ground space  . Since the point

. Since the point  is not an isolated point in the space

is not an isolated point in the space  ,

,  contains infinitely many points of

contains infinitely many points of  . So choose an finite set

. So choose an finite set  with at least

with at least  points such that

points such that  . For the the open set

. For the the open set ![[C,U]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BC%2CU%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) , we have

, we have ![[C,U] \subset [B,U]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BC%2CU%5D+%5Csubset+%5BB%2CU%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and

and ![[C,U]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BC%2CU%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) contains no point of

contains no point of  . With the open set

. With the open set  being a union of countably many closed and nowhere dense sets in

being a union of countably many closed and nowhere dense sets in  , the open set

, the open set  is not of second category. We complete the proof that

is not of second category. We complete the proof that ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is not a Baire space.

is not a Baire space.

__________________________________

To see bullet point 10, let  be an uncountable and pairwise disjoint collection of open subsets of

be an uncountable and pairwise disjoint collection of open subsets of  . For each

. For each  , choose a point

, choose a point  . Then

. Then ![\left\{[\left\{ x_O \right\},O]: O \in \mathcal{O} \right\}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5C%7B%5B%5Cleft%5C%7B+x_O+%5Cright%5C%7D%2CO%5D%3A+O+%5Cin+%5Cmathcal%7BO%7D+%5Cright%5C%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is an uncountable and pairwise disjoint collection of open subsets of

is an uncountable and pairwise disjoint collection of open subsets of ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Thus if

. Thus if ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is CCC then

is CCC then  must have the CCC.

must have the CCC.

__________________________________

To see bullet point 11, let  be uncountable such that

be uncountable such that  as a space is discrete. This means that for each

as a space is discrete. This means that for each  , there exists an open

, there exists an open  such that

such that  and

and  contains no point of

contains no point of  other than

other than  . Then

. Then ![\left\{[\left\{y \right\},O_y]: y \in Y \right\}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5C%7B%5B%5Cleft%5C%7By+%5Cright%5C%7D%2CO_y%5D%3A+y+%5Cin+Y+%5Cright%5C%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is an uncountable and pairwise disjoint collection of open subsets of

is an uncountable and pairwise disjoint collection of open subsets of ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Thus if

. Thus if ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has the CCC, then the ground space

has the CCC, then the ground space  has no uncountable discrete subspace (such a space is said to have countable spread).

has no uncountable discrete subspace (such a space is said to have countable spread).

__________________________________

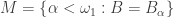

To see bullet point 12, let  be uncountable such that

be uncountable such that  is not Lindelof. Then there exists an open cover

is not Lindelof. Then there exists an open cover  of

of  such that no countable subcollection of

such that no countable subcollection of  can cover

can cover  . We can assume that sets in

. We can assume that sets in  are open subsets of

are open subsets of  . Also by considering a subcollection of

. Also by considering a subcollection of  if necessary, we can assume that cardinality of

if necessary, we can assume that cardinality of  is

is  or

or  . Now by doing a transfinite induction we can choose the following sequence of points and the following sequence of open sets:

. Now by doing a transfinite induction we can choose the following sequence of points and the following sequence of open sets:

such that  if

if  ,

,  and

and  for each

for each  . At each step

. At each step  , all the previously chosen open sets cannot cover

, all the previously chosen open sets cannot cover  . So we can always choose another point

. So we can always choose another point  of

of  and then choose an open set in

and then choose an open set in  that contains

that contains  .

.

Then ![\left\{[\left\{x_\alpha \right\},U_\alpha]: \alpha < \omega_1 \right\}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5C%7B%5B%5Cleft%5C%7Bx_%5Calpha+%5Cright%5C%7D%2CU_%5Calpha%5D%3A+%5Calpha+%3C+%5Comega_1+%5Cright%5C%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a pairwise disjoint collection of open subsets of

is a pairwise disjoint collection of open subsets of ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Thus if

. Thus if ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has the CCC, then

has the CCC, then  must be hereditarily Lindelof.

must be hereditarily Lindelof.

__________________________________

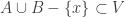

To see bullet point 13, let  . Consider open sets

. Consider open sets ![[A,U]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BA%2CU%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) where

where  ranges over all finite subsets of

ranges over all finite subsets of  and

and  ranges over all open subsets of

ranges over all open subsets of  with

with  . Let

. Let  be a collection of such

be a collection of such ![[A,U]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BA%2CU%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) such that

such that  is pairwise disjoint and

is pairwise disjoint and  is maximal (i.e. by adding one more open set, the collection will no longer be pairwise disjoint). We can apply a Zorn lemma argument to obtain such a maximal collection. Let

is maximal (i.e. by adding one more open set, the collection will no longer be pairwise disjoint). We can apply a Zorn lemma argument to obtain such a maximal collection. Let  be the following subset of

be the following subset of  .

.

We claim that the set  is dense in

is dense in  . Suppose that there is some open set

. Suppose that there is some open set  such that

such that  and

and  . Let

. Let  . Then

. Then ![[\left\{y \right\},W] \cap [A,U]=\varnothing](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Cleft%5C%7By+%5Cright%5C%7D%2CW%5D+%5Ccap+%5BA%2CU%5D%3D%5Cvarnothing&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) for all

for all ![[A,U] \in \mathcal{G}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BA%2CU%5D+%5Cin+%5Cmathcal%7BG%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . So adding

. So adding ![[\left\{y \right\},W]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Cleft%5C%7By+%5Cright%5C%7D%2CW%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) to

to  , we still get a pairwise disjoint collection of open sets, contradicting that

, we still get a pairwise disjoint collection of open sets, contradicting that  is maximal. So

is maximal. So  is dense in

is dense in  .

.

If ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has the CCC, then

has the CCC, then  is countable and

is countable and  is a countable dense subset of

is a countable dense subset of  . Thus if

. Thus if ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has the CCC, the ground space

has the CCC, the ground space  is hereditarily separable.

is hereditarily separable.

__________________________________

A collection  of subsets of a space

of subsets of a space  is said to be a network for the space

is said to be a network for the space  if any non-empty open subset of

if any non-empty open subset of  is the union of elements of

is the union of elements of  , equivalently, for each

, equivalently, for each  and for each open

and for each open  with

with  , there is some

, there is some  with

with  . Note that a network works like a base but the elements of a network do not have to be open. The concept of network and spaces with countable network are discussed in these previous posts Network Weight of Topological Spaces – I and Network Weight of Topological Spaces – II.

. Note that a network works like a base but the elements of a network do not have to be open. The concept of network and spaces with countable network are discussed in these previous posts Network Weight of Topological Spaces – I and Network Weight of Topological Spaces – II.

To see bullet point 14, let  be a network for the ground space

be a network for the ground space  such that

such that  is also countable. Assume that

is also countable. Assume that  is closed under finite unions (for example, adding all the finite unions if necessary). Let

is closed under finite unions (for example, adding all the finite unions if necessary). Let ![\left\{[A_\alpha,U_\alpha]: \alpha < \omega_1 \right\}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5C%7B%5BA_%5Calpha%2CU_%5Calpha%5D%3A+%5Calpha+%3C+%5Comega_1+%5Cright%5C%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) be a collection of basic open sets in

be a collection of basic open sets in ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Then for each

. Then for each  , find

, find  such that

such that  . Since

. Since  is countable, there is some

is countable, there is some  such that

such that  is uncountable. It follows that for any finite

is uncountable. It follows that for any finite  ,

, ![\bigcap \limits_{\alpha \in E} [A_\alpha,U_\alpha] \ne \varnothing](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbigcap+%5Climits_%7B%5Calpha+%5Cin+E%7D+%5BA_%5Calpha%2CU_%5Calpha%5D+%5Cne+%5Cvarnothing&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

Thus if the ground space  has a countable network, then

has a countable network, then ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has the CCC.

has the CCC.

__________________________________

The implications in bullet points 12 and 13 cannot be reversed. Hereditarily Lindelof property and hereditarily separability are not sufficient conditions for ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) to have the CCC. See [4] for a study of the CCC property of the Pixley-Roy spaces.

to have the CCC. See [4] for a study of the CCC property of the Pixley-Roy spaces.

To see bullet point 15, let  be the Sorgenfrey line, i.e. the real line

be the Sorgenfrey line, i.e. the real line  with the topology generated by the half closed intervals of the form

with the topology generated by the half closed intervals of the form  . For each

. For each  , let

, let  . Then

. Then ![\left\{[ \left\{ x \right\},U_x]: x \in S \right\}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5C%7B%5B+%5Cleft%5C%7B+x+%5Cright%5C%7D%2CU_x%5D%3A+x+%5Cin+S+%5Cright%5C%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a collection of pairwise disjoint open sets in

is a collection of pairwise disjoint open sets in ![\mathcal{F}[S]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BS%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

__________________________________

A Moore space is a space with a development. For the definition, see this previous post.

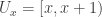

To see bullet point 16, for each  , let

, let  be a decreasing local base at

be a decreasing local base at  . We define a development for the space

. We define a development for the space ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

For each finite  and for each

and for each  , let

, let  . Clearly, the sets

. Clearly, the sets  form a decreasing local base at the finite set

form a decreasing local base at the finite set  . For each

. For each  , let

, let  be the following collection:

be the following collection:

We claim that  is a development for

is a development for ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . To this end, let

. To this end, let  be open in

be open in ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) with

with  . If we make

. If we make  large enough, we have

large enough, we have ![[F,B_n(F)] \subset V](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BF%2CB_n%28F%29%5D+%5Csubset+V&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

For each non-empty proper  , choose an integer

, choose an integer  such that

such that ![[F,B_{f(G)}(F)] \subset V](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BF%2CB_%7Bf%28G%29%7D%28F%29%5D+%5Csubset+V&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and

and  . Let

. Let  be defined by:

be defined by:

We have  for all non-empty proper

for all non-empty proper  . Thus

. Thus ![F \notin [G,B_m(G)]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=F+%5Cnotin+%5BG%2CB_m%28G%29%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) for all non-empty proper

for all non-empty proper  . But in

. But in  , the only sets that contain

, the only sets that contain  are

are ![[F,B_m(F)]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BF%2CB_m%28F%29%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and

and ![[G,B_m(G)]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BG%2CB_m%28G%29%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) for all non-empty proper

for all non-empty proper  . So

. So ![[F,B_m(F)]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BF%2CB_m%28F%29%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is the only set in

is the only set in  that contains

that contains  , and clearly

, and clearly ![[F,B_m(F)] \subset V](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BF%2CB_m%28F%29%5D+%5Csubset+V&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

We have shown that for each open  in

in ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) with

with  , there exists an

, there exists an  such that any open set in

such that any open set in  that contains

that contains  must be a subset of

must be a subset of  . This shows that the

. This shows that the  defined above form a development for

defined above form a development for ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

____________________________________________________________________

Examples

In the original construction of Pixley and Roy, the example was ![\mathcal{F}[\mathbb{R}]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5B%5Cmathbb%7BR%7D%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) . Based on the above discussion,

. Based on the above discussion, ![\mathcal{F}[\mathbb{R}]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5B%5Cmathbb%7BR%7D%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a non-separable CCC Moore space. Because the density (greater than

is a non-separable CCC Moore space. Because the density (greater than  for not separable) and the cellularity (

for not separable) and the cellularity ( for CCC) do not agree,

for CCC) do not agree, ![\mathcal{F}[\mathbb{R}]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5B%5Cmathbb%7BR%7D%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is not metrizable. In fact, it does not even have a dense metrizable subspace. Note that countable subspaces of

is not metrizable. In fact, it does not even have a dense metrizable subspace. Note that countable subspaces of ![\mathcal{F}[\mathbb{R}]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5B%5Cmathbb%7BR%7D%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) are metrizable but are not dense. Any uncountable dense subspace of

are metrizable but are not dense. Any uncountable dense subspace of ![\mathcal{F}[\mathbb{R}]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5B%5Cmathbb%7BR%7D%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is not separable but has the CCC. Not only

is not separable but has the CCC. Not only ![\mathcal{F}[\mathbb{R}]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5B%5Cmathbb%7BR%7D%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is not metrizable, it is not normal. The problem of finding

is not metrizable, it is not normal. The problem of finding  for which

for which ![\mathcal{F}[X]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BX%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is normal requires extra set-theoretic axioms beyond ZFC (see [6]). In fact, Pixley-Roy spaces played a large role in the normal Moore space conjecture. Assuming some extra set theory beyond ZFC, there is a subset

is normal requires extra set-theoretic axioms beyond ZFC (see [6]). In fact, Pixley-Roy spaces played a large role in the normal Moore space conjecture. Assuming some extra set theory beyond ZFC, there is a subset  such that

such that ![\mathcal{F}[M]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathcal%7BF%7D%5BM%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) is a CCC metacompact normal Moore space that is not metrizable (see Example I in [8]).

is a CCC metacompact normal Moore space that is not metrizable (see Example I in [8]).

On the other hand, Pixley-Roy space of the Sorgenfrey line and the Pixley-Roy space of  (the first uncountable ordinal with the order topology) are metrizable (see [3]).

(the first uncountable ordinal with the order topology) are metrizable (see [3]).

The Sorgenfrey line and the first uncountable ordinal are classic examples of topological spaces that demonstrate that topological spaces in general are not as well behaved like metrizable spaces. Yet their Pixley-Roy spaces are nice. The real line and other separable metric spaces are nice spaces that behave well. Yet their Pixley-Roy spaces are very much unlike the ground spaces. This inverse relation between the ground space and the Pixley-Roy space was noted by van Douwen (see [3] and [7]) and is one reason that Pixley-Roy hyperspaces are a good source of counterexamples.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Bennett, H. R., Fleissner, W. G., Lutzer, D. J., Metrizability of certain Pixley-Roy spaces, Fund. Math. 110, 51-61, 1980.

- Daniels, P, Pixley-Roy Spaces Over Subsets of the Reals, Topology Appl. 29, 93-106, 1988.

- Lutzer, D. J., Pixley-Roy topology, Topology Proc. 3, 139-158, 1978.

- Hajnal, A., Juahasz, I., When is a Pixley-Roy Hyperspace CCC?, Topology Appl. 13, 33-41, 1982.

- Pixley, C., Roy, P., Uncompletable Moore spaces, Proc. Auburn Univ. Conf. Auburn, AL, 1969.

- Przymusinski, T., Normality and paracompactness of Pixley-Roy hyperspaces, Fund. Math. 113, 291-297, 1981.

- van Douwen, E. K., The Pixley-Roy topology on spaces of subsets, Set-theoretic Topology, Academic Press, New York, 111-134, 1977.

- Tall, F. D., Normality versus Collectionwise Normality, Handbook of Set-Theoretic Topology (K. Kunen and J. E. Vaughan, eds), Elsevier Science Publishers B. V., Amsterdam, 685-732, 1984.

- Tanaka, H, Normality and hereditary countable paracompactness of Pixley-Roy hyperspaces, Fund. Math. 126, 201-208, 1986.

____________________________________________________________________

to gain insight about the function

. In this post, we draw more continuous functions with the goal of connecting

and

where

is the double arrow space. For example,

can be embedded as a subspace of

. More interestingly, both function spaces

and

share the same closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum. As a result, the function space

is not normal.

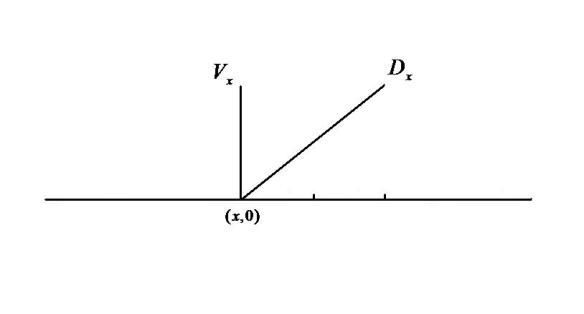

, which is a subset in the Euclidean plane.

with

, a basic open set containing the point

is of the form

, painted red in Figure 2. One the other hand, for any

with

, a basic open set containing the point

is of the form

, painted blue in Figure 2. The upper right point

and the lower left point

are made isolated points.

can be embedded as a subspace in the function

.

and

share the same closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum.

is not normal.

can be embedded into

, we draw a continuous map from the Sorgenfrey line

onto the double arrow space

. The following diagram gives the essential idea of the mapping we need.

onto the upper line segment of the double arrow space, as demonstrated by the red arrow. Thus

for any

with

. Essentially on the interval

, the mapping is the identity map.

onto the lower line segment of the double arrow space less the point

, as demonstrated by the blue arrow in Figure 3. Thus

for any

with

. Essentially on the interval

, the mapping is the identity map times -1.

in the domain. To complete the mapping, let

for any

and

for any

.

be the mapping that has been described. It maps the Sorgenfrey line onto the double arrow space. It is straightforward to verify that the map

is continuous.

can be embedded into

.

is a continuous image of the space

. Then

can be embedded into

.

can be embedded into

. The embedding that makes this true is

for each

. Thus each function

in

is identified with the composition

where

is the map defined in Figure 3. The fact that

is an embedding is shown in this previous post (see Theorem 1).

.

, let

be the continuous function described in Figure 4. The previous post shows that the set

is a closed and discrete subspace of

. We claim that

.

, we define continuous functions

such that

. We can actually back out the map

from

in Figure 4 and the mapping

. Here’s how. The function

is piecewise constant (0 or 1). Let’s focus on the interval

in the domain of

.

maps to the value 1. There are two intervals,

and

, where

maps to 1. The mapping

maps

to the set

. So the function

must map

to the value 1. The mapping

maps

to the set

. So

must map

to the value 1.

maps to the value 0. There are two intervals,

and

, where

maps to 0. The mapping

maps

to the set

. So the function

must map

to the value 0. The mapping

maps

to the set

. So

must map

to the value 0.

and

of the double arrow space, make sure that

maps these two points to the value 0. The following is a precise definition of the function

.

is a translation of

. Under the embedding

defined earlier, we see that

. Let

. The set

in

is homeomorphic to the set

in

. Thus

is a closed and discrete subspace of

since

is a closed and discrete subspace of

.

, the space of continuous functions on the double arrow space, contains a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum. It follows that

is not normal. This is due to the fact that if

is normal, then

must have countable extent (i.e. all closed and discrete subspaces must be countable).

is embedded in

, the function space

is not embedded in

. Because the double arrow space is compact,

has countable tightness. If

were to be embedded in

, then

would be countably tight too. However,

is not countably tight due to the fact that

is not Lindelof (see Theorem 1 in this previous post).

-Theory Problem Book, Topological and Function Spaces, Springer, New York, 2011.

2018 – Dan Ma