The Sorgenfrey line is a well known topological space. It is the real number line with open intervals defined as sets of the form . Though this is a seemingly small tweak, it generates a vastly different space than the usual real number line. In this post, we look at the Sorgenfrey line from the continuous function perspective, in particular, the continuous functions that map the Sorgenfrey line into the real number line. In the process, we obtain insight into the space of continuous functions on the Sorgenfrey line.

The next post is a continuation on the theme of drawing Sorgenfrey continuous functions.

The Sorgenfrey Line

Let denote the real number line. The usual open intervals are of the form

. The union of such open intervals is called an open set. If more than one topologies are considered on the real line, these open sets are referred to as the usual open sets or Euclidean open sets (on the real line). The open intervals

form a base for the usual topology on the real line. One important fact abut the usual open sets is that the usual open sets can be generated by the intervals

where both end points are rational numbers. Thus the usual topology on the real line is said to have a countable base.

Now tweak the usual topology by calling sets of the form open intervals. Then form open sets by taking unions of all such open intervals. The collection of such open sets is called the Sorgenfrey topology (on the real line). The real number line

with the Sorgenfry topology is called the Sorgenfrey line, denoted by

. The Sorgenfrey line has been discussed in this blog, starting with this post. This post examines continuous functions from

into the real line. In the process, we gain insight on the space of continuous functions defined on

.

Note that any usual open interval is the union of intervals of the form

. Thus any usual (Euclidean) open set is an open set in the Sorgenfrey line. Thus the usual topology (on the real line) is contained in the Sorgenfrey topology, i.e. the usual topology is a weaker (coarser) topology.

Let be the set of all continuous functions

where the domain is the real number line with the usual topology. Let

be the set of all continuous functions

where the domain is the Sorgenfrey line. In both cases, the range is always the number line with the usual topology. Based on the preceding paragraph, any continuous function

is also continuous with respect to the Sorgenfrey line, i.e.

.

Pictures of Continuous Functions

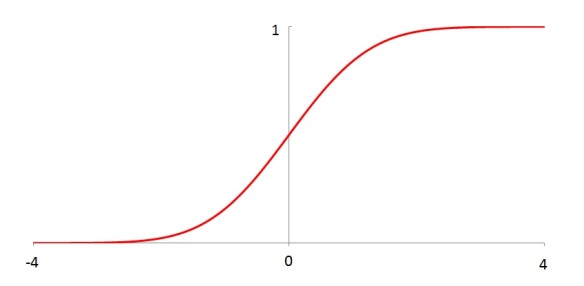

Consider the following two continuous functions.

The first one (Figure 1) is the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the standard normal distribution. The second one (Figure 2) is the CDF of the uniform distribution on the interval where

. Both of these are continuous in the usual Euclidean topology (in the domain). Such graphs would make regular appearance in a course on probability and statistics. They also show up in a calculus course as an everywhere differentiable curve (Figure 1) and as a differentiable curve except at finitely many points (Figure 2). Both of these functions can also be regarded as continuous functions on the Sorgenfrey line.

Consider a function that is continuous in the Sorgenfrey line but not continuous in the usual topology.

Figure 3 is a function that maps the interval to -1 and maps the interval

to 1. It is not continuous in the usual topology because of the jump at

. But it is a continuous function when the domain is considered to be the Sorgenfrey line. Because of the open intervals being

, continuous functions defined on the Sorgenfrey line are right continuous.

The cumulative distribution function of a discrete probability distribution is always right continuous, hence continuous in the Sorgenfrey line. Here’s an example.

Figure 4 is the CDF of the uniform distribution on the finite set , where each point has probability 0.2. There is a jump of height 0.2 at each of the points from 0 to 4. Figure 3 and Figure 4 are step functions. As long as the left point of a step is solid and the right point is hollow, the step functions are continuous on the Sorgenfrey line.

The take away from the last four figures is that the real-valued continuous functions defined on the Sorgenfrey line are right continuous and that step functions (with the left point solid and the right point hollow) are Sorgenfrey continuous.

A Family of Sorgenfrey Continuous Functions

The four examples of continuous functions shown above are excellent examples to illustrate the Sorgenfrey topology. We now introduce a family of continuous functions for

. These continuous functions will lead to additional insight on the function space whose domain space is the Sorgenfrey line.

For any , the following gives the definition and the graph of the function

.

Function Space on the Sorgenfrey Line

This is the place where we switch the focus to function space. The set is a subset of the product space

. So we can consider

as a topological space endowed with the topology inherited as a subspace of

. This topology on

is called the pointwise convergence topology and

with the product subspace topology is denoted by

. See here for comments on how to work with the pointwise convergence topology.

For the present discussion, all we need is some notation on a base for . For

, and for any open interval

(open in the usual topology of the real number line), let

. Then the collection of intersections of finitely many

would form a base for

.

The following is the main fact we wish to establish.

The function space contains a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum. In particular, the set

is a closed and discrete subspace of

.

The above result will derive several facts on the function space , which are discussed in a section below. More interestingly, the proof of the fact that

is a closed and discrete subspace of

is based purely on the definition of the functions

and the Sorgenfrey topology. The proof given below does not use any deep or high powered results from function space theory. So it should be a nice exercise on the Sorgenfrey topology.

I invite readers to either verify the fact independently of the proof given here or follow the proof closely. Lots of drawing of the functions on paper will be helpful in going over the proof. In this one instance at least, drawing continuous functions can help gain insight on function spaces.

Working out the Proof

The following diagram was helpful to me as I worked out the different cases in showing the discreteness of the family . The diagram is a valuable aid in convincing myself that a given case is correct.

Now the proof. First, is relatively discrete in

. We show that for each

, there is an open set

containing

such that

does not contain

for any

. To this end, let

where

and

are the open intervals

and

. With Figure 6 as an aid, it follows that for

,

and for

,

.

The open set contains

, the function in the middle of Figure 6. Note that for

,

and

. Thus

. On the other hand, for

,

and

. Thus

. This proves that the set

is a discrete subspace of

relative to

itself.

Now we show that is closed in

. To this end, we show that

-

for each

Actually, this has already been done above with points that are in

. One thing to point out is that the range of

is

. As we consider

, we only need to consider

that maps into

. Let

. The argument is given in two cases regarding the function

.

Case 1. There exists some such that

.

We assume that and

. Then for all

,

and for all

,

. Let

. Then

and

contains no

for any

and

for any

. To help see this argument, use Figure 6 as a guide. The case that

and

has a similar argument.

Case 2. For every , we have

.

Claim. The function is constant on the interval

. Suppose not. Let

such that

. Suppose that

. Consider

. Clearly the number

is an upper bound of

. Let

be a least upper bound of

. The function

has value 1 on the interval

. Otherwise,

would not be the least upper bound of the set

. There is a sequence of points

in the interval

such that

from the left such that

for all

. Otherwise,

would not be the least upper bound of the set

.

It follows that . Otherwise, the function

is not continuous at

. Now consider the 6 points

. By the assumption in Case 2,

and

. Since

for all

,

for all

. Note that

from the right. Since

is right continuous,

, contradicting

. Thus we cannot have

.

Now suppose we have where

. Consider

. Clearly

has an upper bound, namely the number

. Let

be a least upper bound of

. The function

has value 0 on the interval

. Otherwise,

would not be the least upper bound of the set

. There is a sequence of points

in the interval

such that

from the left such that

for all

. Otherwise,

would not be the least upper bound of the set

.

It follows that . Otherwise, the function

is not continuous at

. Now consider the 6 points

. By the assumption in Case 2,

and

. Since

for all

,

for all

. Note that

from the right. Since

is right continuous,

, contradicting

. Thus we cannot have

.

The claim that the function is constant on the interval

is established. To wrap up, first assume that the function

is 1 on the interval

. Let

. It is clear that

. It is also clear from Figure 5 that

contains no

. Now assume that the function

is 0 on the interval

. Since

is Sorgenfrey continuous, it follows that

. Let

. It is clear that

. It is also clear from Figure 5 that

contains no

.

We have established that the set is a closed and discrete subspace of

.

What does it Mean?

The above argument shows that the set is a closed an discrete subspace of the function space

. We have the following three facts.

| Three Results |

|

To show that is separable, let’s look at one basic helpful fact on

. If

is a separable metric space, e.g.

, then

has quite a few nice properties (discussed here). One is that

is hereditarily separable. Thus

, the space of real-valued continuous functions defined on the number line with the pointwise convergence topology, is hereditarily separable and thus separable. Recall that continuous functions in

are also Soregenfrey line continuous. Thus

is a subspace of

. The space

is also a dense subspace of

. Thus the space

contains a dense separable subspace. It means that

is separable.

Secondly, is not hereditarily separable since the subspace

is a closed and discrete subspace.

Thirdly, is not a normal space. According to Jones’ lemma, any separable space with a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality of continuum is not a normal space (see Corollary 1 here). The subspace

is a closed and discrete subspace of the separable space

. Thus

is not normal.

Remarks

The topology of the Sorgenfrey line is vastly different from the usual topology on the real line even though the the Sorgenfrey topology is obtained by a seemingly small tweak from the usual topology. The real line is a metric space while the Sorgenfrey line is not metrizable. The real number line is connected while the Sorgenfrey line is not. The countable power of the real number line is a metric space and thus a normal space. On the other hand, the Sorgenfrey line is a classic example of a normal space whose square is not normal. See here for a basic discussion of the Sorgenfrey line.

The pictures of Sorgenfrey continuous functions demonstrated here show that the real number line and the Sorgenfrey line are also very different from a function space perspective. The function space has a whole host of nice properties: normal, Lindelof (hence paracompact and collectionwise normal), hereditarily Lindelof (hence hereditarily normal), hereditarily separable, and perfectly normal (discussed here).

Though separable, the function space contains a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum, making it not hereditarily separable and not normal.

For more information about in general and

in particular, see [1] and [2]. A different proof that

contains a closed and discrete subspace of cardinality continuum can be found in Problem 165 in [2].

The next post is a continuation on the theme of drawing Sorgenfrey continuous functions.

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

- Tkachuk V. V., A

-Theory Problem Book, Topological and Function Spaces, Springer, New York, 2011.

2017 – Dan Ma

Normality in Cp(X)

Any collectionwise normal space is a normal space. Any perfectly normal space is a hereditarily normal space. In general these two implications are not reversible. In function spaces , the two implications are reversible. There is a normal space that is not countably paracompact (such a space is called a Dowker space). If a function space

is normal, it is countably paracompact. Thus normality in

is a strong property. This post draws on Dowker’s theorem and other results, some of them are previously discussed in this blog, to discuss this remarkable aspect of the function spaces

.

Since we are discussing function spaces, the domain space has to have sufficient quantity of real-valued continuous functions, e.g. there should be enough continuous functions to separate the points from closed sets. The ideal setting is the class of completely regular spaces (also called Tychonoff spaces). See here for a discussion on completely regular spaces in relation to function spaces.

Let be a completely regular space. Let

be the set of all continuous functions from

into the real line

. When

is endowed with the pointwise convergence topology, the space is denoted by

(see here for further comments on the definition of the pointwise convergence topology).

When Function Spaces are Normal

Let be a completely regular space. We discuss these four facts of

:

- If the function space

is normal, then

is countably paracompact.

- If the function space

is hereditarily normal, then

is perfectly normal.

- If the function space

is normal, then

is collectionwise normal.

- Let

be a normal space. If

is normal, then

has countable extent, i.e. every closed and discrete subset of

is countable, implying that

is collectionwise normal.

Fact #1 and Fact #2 rely on a representation of as a product space with one of the factors being the real line. For

, let

. Then

. This representation is discussed here.

Another useful tool is Dowker’s theorem, which essentially states that for any normal space , the space

is countably paracompact if and only if

is normal for all compact metric space

if and only if

is normal. For the full statement of the theorem, see Theorem 1 in this previous post, which has links to the proofs and other discussion.

To show Fact #1, suppose that is normal. Immediately we make use of the representation

where

. Since

is normal,

is also normal. By Dowker’s theorem,

is countably paracompact. Note that

is a closed subspace of the normal

. Thus

is also normal.

One more helpful tool is Theorem 5 in in this previous post, which is like an extension of Dowker’s theorem, which states that a normal space is countably paracompact if and only if

is normal for any

-compact metric space

. This means that

is normal.

We want to show is countably paracompact. Since

is normal (based on the argument in the preceding paragraph),

is normal. Thus according to Dowker’s theorem,

is countably paracompact.

For Fact #2, a helpful tool is Katetov’s theorem (stated and proved here), which states that for any hereditarily normal , one of the factors is perfectly normal or every countable subset of the other factor is closed (in that factor).

To show Fact #2, suppose that is hereditarily normal. With

and according to Katetov’s theorem,

must be perfectly normal. The product of a perfectly normal space and any metric space is perfectly normal (a proof is found here). Thus

is perfectly normal.

The proof of Fact #3 is found in Problems 294 and 295 of [2]. The key to the proof is a theorem by Reznichenko, which states that any dense convex normal subspace of has countable extent, hence is collectionwise normal (problem 294). See here for a proof that any normal space with countable extent is collectionwise normal (see Theorem 2). The function space

is a dense convex subspace of

(problem 295). Thus if

is normal, then it has countable extent and hence collectionwise normal.

Fact #4 says that normality of the function space imposes countable extent on the domain. This result is discussed in this previous post (see Corollary 3 and Corollary 5).

Remarks

The facts discussed here give a flavor of what function spaces are like when they are normal spaces. For further and deeper results, see [1] and [2].

Fact #1 is essentially driven by Dowker’s theorem. It follows from the theorem that whenever the product space is normal, one of the factor must be countably paracompact if the other factor has a non-trivial convergent sequence (see Theorem 2 in this previous post). As a result, there is no Dowker space that is a

. No pathology can be found in

with respect to finding a Dowker space. In fact, not only

is normal for any compact metric space

, it is also true that

is normal for any

-compact metric space

when

is normal.

The driving force behind Fact #2 is Katetov’s theorem, which basically says that the hereditarily normality of is a strong statement. Coupled with the fact that

is of the form

, Katetov’s theorem implies that

is perfectly normal. The argument also uses the basic fact that perfectly normality is preserved when taking product with metric spaces.

There are examples of normal but not collectionwise normal spaces (e.g. Bing’s Example G). Resolution of the question of whether normal but not collectionwise normal Moore space exists took extensive research that spanned decades in the 20th century (the normal Moore space conjecture). The function is outside of the scope of the normal Moore space conjecture. The function space

is usually not a Moore space. It can be a Moore space only if the domain

is countable but then

would be a metric space. However, it is still a powerful fact that if

is normal, then it is collectionwise normal.

On the other hand, a more interesting point is on the normality of . Suppose that

is a normal Moore space. If

happens to be normal, then Fact #4 says that

would have to be collectionwise normal, which means

is metrizable. If the goal is to find a normal Moore space

that is not collectionwise normal, the normality of

would kill the possibility of

being the example.

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

- Tkachuk V. V., A

-Theory Problem Book, Topological and Function Spaces, Springer, New York, 2011.

2017 – Dan Ma

Looking for spaces in which every compact subspace is metrizable

Once it is known that a topological space is not metrizable, it is natural to ask, from a metrizability standpoint, which subspaces are metrizable, e.g. whether every compact subspace is metrizable. This post discusses several classes of spaces in which every compact subspace is metrizable. Though the goal here is not to find a complete characterization of such spaces, this post discusses several classes of spaces and various examples that have this property. The effort brings together many interesting basic and well known facts. Thus the notion “every compact subspace is metrizable” is an excellent learning opportunity.

Several Classes of Spaces

The notion “every compact subspace is metrizable” is a very broad class of spaces. It includes well known spaces such as Sorgenfrey line, Michael line and the first uncountable ordinal (with the order topology) as well as Moore spaces. Certain function spaces are in the class “every compact subspace is metrizable”. The following diagram is a good organizing framework.

Let be a space. It is submetrizable if there is a topology

on the set

such that

and

is a metrizable space. The topology

is said to be weaker (coarser) than

. Thus a space

is submetrizable if it has a weaker metrizable topology.

Let be a set of subsets of the space

.

is said to be a network for

if for every open subset

of

and for each

, there exists

such that

. Having a network that is countable in size is a strong property (see here for a discussion on spaces with a countable network).

The diagonal of the space is the subset

of the square

. The space

has a

-diagonal if

is a

-subset of

, i.e.

is the intersection of countably many open subsets of

.

The implication is clear. For

, see Lemma 1 in this previous post on countable network. The implication

is left as an exercise. To see

, let

be a compact subset of

. The property of having a

-diagonal is hereditary. Thus

has a

-diagonal. According to a well known result, any compact space with a

-diagonal is metrizable (see here).

None of the implications in the diagram is reversible. The first uncountable ordinal is an example for

. This follows from the well known result that any countably compact space with a

-diagonal is metrizable (see here). The Mrowka space is an example for

(see here). The Sorgenfrey line is an example for both

and

.

To see where the examples mentioned earlier are placed, note that Sorgenfrey line and Michael line are submetrizable, both are submetrizable by the usual Euclidean topology on the real line. Each compact subspace of the space is countable and is thus contained in some initial segment

which is metrizable. Any Moore space has a

-diagonal. Thus compact subspaces of a Moore space are metrizable.

Function Spaces

We now look at some function spaces that are in the class “every compact subspace is metrizable.” For any Tychonoff space (completely regular space) ,

is the space of all continuous functions from

into

with the pointwise convergence topology (see here for basic information on pointwise convergence topology).

Theorem 1

Suppose that is a separable space. Then every compact subspace of

is metrizable.

Proof

The proof here actually shows more than is stated in the theorem. We show that is submetrizable by a separable metric topology. Let

be a countable dense subspace of

. Then

is metrizable and separable since it is a subspace of the separable metric space

. Thus

has a countable base. Let

be a countable base for

.

Let be the restriction map, i.e. for each

,

. Since

is a projection map, it is continuous and one-to-one and it maps

into

. Thus

is a continuous bijection from

into

. Let

.

We claim that is a base for a topology on

. Once this is established, the proof of the theorem is completed. Note that

is countable and elements of

are open subsets of

. Thus the topology generated by

is coarser than the original topology of

.

For to be a base, two conditions must be satisfied –

is a cover of

and for

, and for

, there exists

such that

. Since

is a base for

and since elements of

are preimages of elements of

under the map

, it is straightforward to verify these two points.

Theorem 1 is actually a special case of a duality result in function space theory. More about this point later. First, consider a corollary of Theorem 1.

Corollary 2

Let where

is the cardinality continuum and each

is a separable space. Then every compact subspace of

is metrizable.

The key fact for Corollary 2 is that the product of continuum many separable spaces is separable (this fact is discussed here). Theorem 1 is actually a special case of a deep result.

Theorem 3

Suppose that is a product of separable spaces where

is any infinite cardinal. Then every compact subspace of

is metrizable.

Theorem 3 is a much more general result. The product of any arbitrary number of separable spaces is not separable if the number of factors is greater than continuum. So the proof for Theorem 1 will not work in the general case. This result is Problem 307 in [2].

A Duality Result

Theorem 1 is stated in a way that gives the right information for the purpose at hand. A more correct statement of Theorem 1 is: is separable if and only if

is submetrizable by a separable metric topology. Of course, the result in the literature is based on density and weak weight.

The cardinal function of density is the least cardinality of a dense subspace. For any space , the weight of

, denoted by

, is the least cardinaility of a base of

. The weak weight of a space

is the least

over all space

for which there is a continuous bijection from

onto

. Thus if the weak weight of

is

, then there is a continuous bijection from

onto some separable metric space, hence

has a weaker separable metric topology.

There is a duality result between density and weak weight for and

. The duality result:

The density of coincides with the weak weight of

and the weak weight of

coincides with the density of

. These are elementary results in

-theory. See Theorem I.1.4 and Theorem I.1.5 in [1].

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

- Tkachuk V. V., A

-Theory Problem Book, Topological and Function Spaces, Springer, New York, 2011.

2017 – Dan Ma

Comparing two function spaces

Let be the first uncountable ordinal, and let

be the successor ordinal to

. Furthermore consider these ordinals as topological spaces endowed with the order topology. It is a well known fact that any continuous real-valued function

defined on either

or

is eventually constant, i.e., there exists some

such that the function

is constant on the ordinals beyond

. Now consider the function spaces

and

. Thus individually, elements of these two function spaces appear identical. Any

matches a function

where

is the result of adding the point

to

where

is the eventual constant real value of

. This fact may give the impression that the function spaces

and

are identical topologically. The goal in this post is to demonstrate that this is not the case. We compare the two function spaces with respect to some convergence properties (countably tightness and Frechet-Urysohn property) as well as normality.

____________________________________________________________________

Tightness

One topological property that is different between and

is that of tightness. The function space

is countably tight, while

is not countably tight.

Let be a space. The tightness of

, denoted by

, is the least infinite cardinal

such that for any

and for any

with

, there exists

for which

and

. When

, we say that

has countable tightness or is countably tight. When

, we say that

has uncountable tightness or is uncountably tight.

First, we show that the tightness of is greater than

. For each

, define

such that

for all

and

for all

. Let

be the function that is identically zero. Then

where

is defined by

. It is clear that for any countable

,

. Thus

cannot be countably tight.

The space is a compact space. The fact that

is countably tight follows from the following theorem.

Theorem 1

Let be a completely regular space. Then the function space

is countably tight if and only if

is Lindelof for each

.

Theorem 1 is a special case of Theorem I.4.1 on page 33 of [1] (the countable case). One direction of Theorem 1 is proved in this previous post, the direction that will give us the desired result for .

____________________________________________________________________

The Frechet-Urysohn property

In fact, has a property that is stronger than countable tightness. The function space

is a Frechet-Urysohn space (see this previous post). Of course,

not being countably tight means that it is not a Frechet-Urysohn space.

____________________________________________________________________

Normality

The function space is not normal. If

is normal, then

would have countable extent. However, there exists an uncountable closed and discrete subset of

(see this previous post). On the other hand,

is Lindelof. The fact that

is Lindelof is highly non-trivial and follows from [2]. The author in [2] showed that if

is a space consisting of ordinals such that

is first countable and countably compact, then

is Lindelof.

____________________________________________________________________

Embedding one function space into the other

The two function space and

are very different topologically. However, one of them can be embedded into the other one. The space

is the continuous image of

. Let

be a continuous surjection. Define a map

by letting

. It is shown in this previous post that

is a homeomorphism. Thus

is homeomorphic to the image

in

. The map

is also defined in this previous post.

The homeomposhism tells us that the function space

, though Lindelof, is not hereditarily normal.

On the other hand, the function space cannot be embedded in

. Note that

is countably tight, which is a hereditary property.

____________________________________________________________________

Remark

There is a mapping that is alluded to at the beginning of the post. Each is associated with

which is obtained by appending the point

to

where

is the eventual constant real value of

. It may be tempting to think of the mapping

as a candidate for a homeomorphism between the two function spaces. The discussion in this post shows that this particular map is not a homeomorphism. In fact, no other one-to-one map from one of these function spaces onto the other function space can be a homeomorphism.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

- Buzyakova, R. Z., In search of Lindelof

‘s, Comment. Math. Univ. Carolinae, 45 (1), 145-151, 2004.

____________________________________________________________________

Cp(omega 1 + 1) is monolithic and Frechet-Urysohn

This is another post that discusses what is like when

is a compact space. In this post, we discuss the example

where

is the first compact uncountable ordinal. Note that

is the successor to

, which is the first (or least) uncountable ordinal. The function space

is monolithic and is a Frechet-Urysohn space. Interestingly, the first property is possessed by

for all compact spaces

. The second property is possessed by all compact scattered spaces. After we discuss

, we discuss briefly the general results for

.

____________________________________________________________________

Initial discussion

The function space is a dense subspace of the product space

. In fact,

is homeomorphic to a subspace of the following subspace of

:

The subspace is the

-product of

many copies of the real line

. The

-product of separable metric spaces is monolithic (see here). The

-product of first countable spaces is Frechet-Urysohn (see here). Thus

has both of these properties. Since the properties of monolithicity and being Frechet-Urysohn are carried over to subspaces, the function space

has both of these properties. The key to the discussion is then to show that

is homeopmophic to a subspace of the

-product

.

____________________________________________________________________

Connection to -product

We show that the function space is homeomorphic to a subspace of the

-product of

many copies of the real lines. Let

be the following subspace of

:

Every function in has non-zero values at only countably points of

. Thus

can be regarded as a subspace of the

-product

.

By Theorem 1 in this previous post, , i.e, the function space

is homeomorphic to the product space

. On the other hand, the product

can also be regarded as a subspace of the

-product

. Basically adding one additional factor of the real line to

still results in a subspace of the

-product. Thus we have:

Thus possesses all the hereditary properties of

. Another observation we can make is that

is not hereditarily normal. The function space

is not normal (see here). The

-product

is normal (see here). Thus

is not hereditarily normal.

____________________________________________________________________

A closer look at

In fact has a stronger property that being monolithic. It is strongly monolithic. We use homeomorphic relation in (1) above to get some insight. Let

be a homeomorphism from

onto

. For each

, let

be defined as follows:

Clearly . Furthermore

can be considered as a subspace of

and is thus metrizable. Let

be a countable subset of

. Then

for some

. The set

is metrizable. The set

is also a closed subset of

. Then

is contained in

and is therefore metrizable. We have shown that the closure of every countable subspace of

is metrizable. In other words, every separable subspace of

is metrizable. This property follows from the fact that

is strongly monolithic.

____________________________________________________________________

Monolithicity and Frechet-Urysohn property

As indicated at the beginning, the -product

is monolithic (in fact strongly monolithic; see here) and is a Frechet-Urysohn space (see here). Thus the function space

is both strongly monolithic and Frechet-Urysohn.

Let be an infinite cardinal. A space

is

-monolithic if for any

with

, we have

. A space

is monolithic if it is

-monolithic for all infinite cardinal

. It is straightforward to show that

is monolithic if and only of for every subspace

of

, the density of

equals to the network weight of

, i.e.,

. A longer discussion of the definition of monolithicity is found here.

A space is strongly

-monolithic if for any

with

, we have

. A space

is strongly monolithic if it is strongly

-monolithic for all infinite cardinal

. It is straightforward to show that

is strongly monolithic if and only if for every subspace

of

, the density of

equals to the weight of

, i.e.,

.

In any monolithic space, the density and the network weight coincide for any subspace, and in particular, any subspace that is separable has a countable network. As a result, any separable monolithic space has a countable network. Thus any separable space with no countable network is not monolithic, e.g., the Sorgenfrey line. On the other hand, any space that has a countable network is monolithic.

In any strongly monolithic space, the density and the weight coincide for any subspace, and in particular any separable subspace is metrizable. Thus being separable is an indicator of metrizability among the subspaces of a strongly monolithic space. As a result, any separable strongly monolithic space is metrizable. Any separable space that is not metrizable is not strongly monolithic. Thus any non-metrizable space that has a countable network is an example of a monolithic space that is not strongly monolithic, e.g., the function space . It is clear that all metrizable spaces are strongly monolithic.

The function space is not separable. Since it is strongly monolithic, every separable subspace of

is metrizable. We can see this by knowing that

is a subspace of the

-product

, or by using the homeomorphism

as in the previous section.

For any compact space ,

is countably tight (see this previous post). In the case of the compact uncountable ordinal

,

has the stronger property of being Frechet-Urysohn. A space

is said to be a Frechet-Urysohn space (also called a Frechet space) if for each

and for each

, if

, then there exists a sequence

such that the sequence converges to

. As we shall see below,

is rarely Frechet-Urysohn.

____________________________________________________________________

General discussion

For any compact space ,

is monolithic but does not have to be strongly monolithic. The monolithicity of

follows from the following theorem, which is Theorem II.6.8 in [1].

Theorem 1

Then the function space is monolithic if and only if

is a stable space.

See chapter 3 section 6 of [1] for a discussion of stable spaces. We give the definition here. A space is stable if for any continuous image

of

, the weak weight of

, denoted by

, coincides with the network weight of

, denoted by

. In [1],

is notated by

. The cardinal function

is the minimum cardinality of all

, the weight of

, for which there exists a continuous bijection from

onto

.

All compact spaces are stable. Let be compact. For any continuous image

of

,

is also compact and

, since any continuous bijection from

onto any space

is a homeomorphism. Note that

always holds. Thus

implies that

. Thus we have:

Corollary 2

Let be a compact space. Then the function space

is monolithic.

However, the strong monolithicity of does not hold in general for

for compact

. As indicated above,

is monolithic but not strongly monolithic. The following theorem is Theorem II.7.9 in [1] and characterizes the strong monolithicity of

.

Theorem 3

Let be a space. Then

is strongly monolithic if and only if

is simple.

A space is

-simple if whenever

is a continuous image of

, if the weight of

, then the cardinality of

. A space

is simple if it is

-simple for all infinite cardinal numbers

. Interestingly, any separable metric space that is uncountable is not

-simple. Thus

is not

-simple and

is not strongly monolithic, according to Theorem 3.

For compact spaces ,

is rarely a Frechet-Urysohn space as evidenced by the following theorem, which is Theorem III.1.2 in [1].

Theorem 4

Let be a compact space. Then the following conditions are equivalent.

is a Frechet-Urysohn space.

is a k-space.

- The compact space

is a scattered space.

A space is a scattered space if for every non-empty subspace

of

, there exists an isolated point of

(relative to the topology of

). Any space of ordinals is scattered since every non-empty subset has a least element. Thus

is a scattered space. On the other hand, the unit interval

with the Euclidean topology is not scattered. According to this theorem,

cannot be a Frechet-Urysohn space.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

____________________________________________________________________

A useful representation of Cp(X)

Let be a completely regular space. The space

is the space of all real-valued continuous functions defined on

endowed with the pointwise convergence topology. In this post, we show that

can be represented as the product of a subspace of

with the real line

. We prove the following theorem. See here for an application of this theorem.

Theorem 1

Let be a completely regular space. Let

. Let

be defined by:

Then is homeomorphic to

.

The above theorem can be found in [1] (see Theorem I.5.4 on p. 37). In [1], the homeomorphism is stated without proof. For the sake of completeness, we provide a detailed proof of Theorem 1.

Proof of Theorem 1

Define by

for any

. The map

is a homeomorphism.

The map is one-to-one

First, we show that it is a one-to-one map. Let where

. Assume that

. Then

. So assume that

. Then the functions

and

are different, which means

.

The map is onto

Now we show maps

onto

. Let

. Let

. Note that

. Then

. We have

.

Note. Showing the continuity of and

is a matter of working with the basic open sets in the function space carefully (e.g. making the necessary shifting). Some authors just skip the details and declare them continuous, e.g. [1]. Readers are welcome to work out enough of the details to see the key idea.

The map is continuous

Show that is continuous. Let

. Let

be an open set in

such that

and,

where are arbitrary points in

and

is some large positive integer. Define the following:

Then define the open set as follows:

Clearly . We need to show

. Let

. Then

. We need to show that

and

. Note that

. For each

,

. So we have the following:

Subtracting the above two inequalities, we have the following:

The above inequality shows that for each ,

. Hence

. It is clear that

. This completes the proof that the map

is continuous.

The inverse is continuous

We now show that is continuous. Let

. Note that

. Let

be an open set in

such that

and

where are arbitrary points of

and

is some large positive integer. Now define an open subset

of

such that

and

We need to show that . Let

. We then have the following inequalities.

Adding the above two inequalities, we obtain:

The above implies that ,

. It is clear that

. Thus

. This completes the proof that

is continuous.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

____________________________________________________________________

A useful embedding for Cp(X)

Let be a Tychonoff space (also called completely regular space). By

we mean the space of all continuous real-valued functions defined on

endowed with the pointwise convergence topology. In this post we discuss a scenario in which a function space can be embedded into another function space. We prove the following theorem. An example follows the proof.

Theorem 1

Suppose that the space is a continuous image of the space

. Then

can be embedded into

.

Proof of Theorem 1

Let be a continuous surjection, i.e.,

is a continuous function from

onto

. Define the map

by

for all

. We show that

is a homeomorphism from

into

.

First we show is a one-to-one map. Let

with

. There exists some

such that

. Choose some

such that

. Then

since

and

.

Next we show that is continuous. Let

. Let

be open in

with

such that

where are arbitrary points of

and each

is an open interval of the real line

. Note that for each

,

. Now consider the open set

defined by:

Clearly . It follows that

since for each

, it is clear that

.

Now we show that is continuous. Let

where

. Let

be open with

such that

where are arbitrary points of

and each

is an open interval of

. Choose

such that

for each

. We have

for each

. Define the open set

by:

Clearly . Note that

. To see this, let

where

. Now

for each

. Thus

. It follows that

is continuous. The proof of the theorem is now complete.

____________________________________________________________________

Example

The proof of Theorem 1 is not difficult. It is a matter of notating carefully the open sets in both function spaces. However, the embedding makes it easy in some cases to understand certain function spaces and in some cases to relate certain function spaces.

Let be the first uncountable ordinal, and let

be the successor ordinal to

. Furthermore consider these ordinals as topological spaces endowed with the order topology. As an application of Theorem 1, we show that

can be embedded as a subspace of

. Define a continuous surjection

as follows:

The map is continuous from

onto

. By Theorem 1,

can be embedded as a subspace of

. On the other hand,

cannot be embedded in

. The function space

is a Frechet-Urysohn space, which is a property that is carried over to any subspace. The function

is not Frechet-Urysohn. Thus

cannot be embedded in

. A further comparison of these two function spaces is found in this subsequent post.

____________________________________________________________________

Cp(X) is countably tight when X is compact

Let be a completely regular space (also called Tychonoff space). If

is a compact space, what can we say about the function space

, the space of all continuous real-valued functions with the pointwise convergence topology? When

is an uncountable space,

is not first countable at every point. This follows from the fact that

is a dense subspace of the product space

and that no dense subspace of

can be first countable when

is uncountable. However, when

is compact,

does have a convergence property, namely

is countably tight.

____________________________________________________________________

Tightness

Let be a completely regular space. The tightness of

, denoted by

, is the least infinite cardinal

such that for any

and for any

with

, there exists

for which

and

. When

, we say that

has countable tightness or is countably tight. When

, we say that

has uncountable tightness or is uncountably tight. Clearly any first countable space is countably tight. There are other convergence properties in between first countability and countable tightness, e.g., the Frechet-Urysohn property. The notion of countable tightness and tightness in general is discussed in further details here.

The fact that is countably tight for any compact

follows from the following theorem.

Theorem 1

Let be a completely regular space. Then the function space

is countably tight if and only if

is Lindelof for each

.

Theorem 1 is the countable case of Theorem I.4.1 on page 33 of [1]. We prove one direction of Theorem 1, the direction that will give us the desired result for where

is compact.

Proof of Theorem 1

The direction

Suppose that is Lindelof for each positive integer. Let

and

where

. For each positive integer

, we define an open cover

of

.

Let be a positive integer. Let

. Since

, there is an

such that

for all

. Because both

and

are continuous, for each

, there is an open set

with

such that

for all

. Let the open set

be defined by

. Let

.

For each , choose

be countable such that

is a cover of

. Let

. Let

. Note that

is countable and

.

We now show that . Choose an arbitrary positive integer

. Choose arbitrary points

. Consider the open set

defined by

We wish to show that . Choose

such that

where

. Consider the function

that goes with

. It is clear from the way

is chosen that

for all

. Thus

, leading to the conclusion that

. The proof that

is countably tight is completed.

The direction

See Theorem I.4.1 of [1].

____________________________________________________________________

Remarks

As shown above, countably tightness is one convergence property of that is guaranteed when

is compact. In general, it is difficult for

to have stronger convergence properties such as the Frechet-Urysohn property. It is well known

is Frechet-Urysohn. According to Theorem II.1.2 in [1], for any compact space

,

is a Frechet-Urysohn space if and only if the compact space

is a scattered space.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

____________________________________________________________________

Cp(omega 1 + 1) is not normal

In this and subsequent posts, we consider where

is a compact space. Recall that

is the space of all continuous real-valued functions defined on

and that it is endowed with the pointwise convergence topology. One of the compact spaces we consider is

, the first compact uncountable ordinal. There are many interesting results about the function space

. In this post we show that

is not normal. An even more interesting fact about

is that

does not have any dense normal subspace [1].

Let be the first uncountable ordinal, and let

be the successor ordinal to

. The set

is the first uncountable ordinal. Furthermore consider these ordinals as topological spaces endowed with the order topology. As mentioned above, the space

is the first compact uncountable ordinal. In proving that

is not normal, a theorem that is due to D. P. Baturov is utilized [2]. This theorem is also proved in this previous post.

For the basic working of function spaces with the pointwise convergence topology, see the post called Working with the function space Cp(X).

The fact that is not normal is established by the following two points.

- If

is normal, then

has countable extent, i.e. every closed and discrete subspace of

is countable.

- There exists an uncountable closed and discrete subspace of

.

We discuss each of the bullet points separately.

The function space is a dense subspace of

, the product of

many copies of

. According to a result of D. P. Baturov [2], any dense normal subspace of the product of

many separable metric spaces has countable extent (also see Theorem 1a in this previous post). Thus

cannot be normal if the second bullet point above is established.

Now we show that there exists an uncountable closed and discrete subspace of . For each

with

, define

by:

Clearly, for each

. Let

. We show that

is a closed and discrete subspace of

. The fact that

is closed in

is establish by the following claim.

Let . We wish to establish the following claim. Once the claim is established, it follows that

is a closed subset of

.

Claim 1

There exists an open subset of

such that

and

.

Consider the two mutually exclusive cases. Case 1. There exists some such that

. Case 2.

.

For Case 1, let . Clearly

and

.

Now assume Case 2. Within this case, there are three sub cases. Case 2.1. is a constant function with value 0. Case 2.2.

is a constant function with value 1. Case 2.3.

is not a constant function.

Case 2.1. If for all

, then consider the open set

where

. Clearly

and

.

Case 2.2. Suppose is a constant function with value 1. Then let

be the open set:

. It is clear that no function in

can be in

.

Case 2.3. Suppose is not a constant function. This case be broken down into two cases. Case 2.3.1.

. Case 2.3.2.

.

Case 2.3.1. Just like in Case 2.2, let . Then

and

.

Case 2.3.2. Assume that . Since

is not a constant function, it must takes on a value of 1 at some point. Let

be the largest such that

. This

exists because

is continuous and

. This case can be further broken into 2 cases. Case 2.3.2.1. There exists

such that

. Case 2.3.2.2.

for all

.

Case 2.3.2.1. Define . Note that

and

.

Case 2.3.2.2. In this case, for all

and

for all

. This means that

. This is a contradiction since

.

In all the cases except the last one, Claim 1 is true. The last case is not possible. Thus Claim 1 is established. The set is a closed subset of

.

Next we show that is discrete in

. Fix

where

. Let

. It is clear that

. Furthermore,

for all

and

for all

. Thus

is open such that

. This completes the proof that

is discrete.

We have established that is an uncountable closed and discrete subspace of

. This implies that

is not normal.

Remarks

The set as defined above is closed and discrete in

. However, the set

is not discrete in a larger subspace of the product space. The set

is also a subset of the following

-product:

Because is the

-product of separable metric spaces, it is normal (see here). By Theorem 1a in this previous post,

would have countable extent. Thus the set

cannot be closed and discrete in

. We can actually see this directly. Let

be a limit ordinal. Define

by

for all

and

for all

. Clearly

and

. Furthermore,

(the closure is taken in

).

The function space , in contrast, is a Lindelof space and hence a normal space. If we restrict the above defined functions

to just

, would the resulting functions form a closed and discrete set in

? For each

with

, let

. Let

.

Is a closed and discrete subset of

? It turns out that

is a discrete subspace of

(relatively discrete). However it is not closed in

. Let

that takes on the constant value of 1. It follows that

(the closure is in

).

It seems that the argument above for showing is closed and discrete in

can be repeated for

. Note that the argument for

relies on the fact that the functions

takes on a value at the point

. So the same argument cannot show that

is a closed and discrete set. Thus

is not discrete in

. Because

is Lindelof (hence normal), it has countable extent. It follows that any uncountable discrete subspace of

cannot be closed in

(the set

is a demonstration). Any uncountable closed subset of

cannot be closed.

Reference

- Arhangel’skii, A. V., Normality and Dense Subspaces, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc., 48, no. 2, 283-291, 2001.

- Baturov, D. P., Normality in dense subspaces of products, Topology Appl., 36, 111-116, 1990.

2014-2018 – Dan Ma

Revised 9/17/2018

The canonical evaluation map with a function space perspective

The evaluation map is a useful tool for embedding a space into a product space and plays an important role in many theorems and problems in topology. See here for a previous discussion. In this post, we present the evaluation map with the perspective that the map can be used for embedding a space into a function space of continuous functions. This post will be useful background for subsequent posts on . In this post, we take a leisurely approach in setting up the scene. Once the map is defined properly, we show what additional conditions will make the evaluation map a homeomorphism. Then a function space perspective is presented as indicated above. After presenting an application, we conclude with some special cases for evaluation maps.

____________________________________________________________________

The general setting

Let be a set (later we will add a topology). Let

be a set of real-valued functions defined on

. Another way to view

is that it is a subspace of the product space

. For each

, consider the map

defined by

for all

. One way to look at

is that it is the projection map from the product space

to one of the factors. Thus

is continuous when

has the product topology. In fact, the product topology is the smallest topology that can be defined on

that would make the

continuous. When we restrict the map

to the subspace

, the map

is still continuous.

One more comment before defining the evaluation map. The set of functions is a subspace of the product space

. Therefore the set

inherits the subspace topology from the product space. It makes sense to consider the function space

, the space of all continuous real-valued functions defined on

endowed with the pointwise convergence topology. Thus we can write

.

We now define the evaluation map. Define the map by letting

for each

, or more explicitly, by letting, for each

,

be the map such that

for all

.

The map is called the evaluation map defined by the family

. When the set

is understood, we can omit the subscript and denote the evaluation map by

. We say

is the canonical evaluation map.

____________________________________________________________________

What makes the evaluation map works

The goal of the evaluation map is that it be a homeomorphism. For that to happen, we need to make a few more additional assumptions. In defining the evaluation map above, the functions in the family are not required to be continuous. In fact, the set

is just a set in the above section. Now we require that

is a topological space (it must be a completely regular space) and that all functions in

are continuous. Thus we have

. With this assumption, the evaluation map is then a continuous function. We have the following theorem.

Theorem 1

Let be a space. Let

. Then the evaluation map

is always continuous.

Proof of Theorem 1

Let . Let

be open in

with

such that

where are arbitrary points of

and each

is an open interval of

. For each

,

. Let

, which is open in

since each

is a continuous function. We show that

. For each

and for each

,

. This means that for each

,

. The continuity of the evaluation map is established.

In order to make the evaluation map a homeomorphism, we consider two more definitions. A family is said to separate points of

if for any

with

, there exists an

such that

. A family

is said to separate points from closed subsets of

if for each

and for each closed subset

of

with

, there exists an

such that

. We have the following theorem.

Theorem 2

Let be a space. Let

. Then the following are true about the evaluation map

.

- If

separates the points of

, then the evaluation map

is a one-to-one.

- If

separates the points from closed subsets of

, then the evaluation map

is a homeomorphism.

Proof of Theorem 2

To prove the bullet point 1, suppose that separates the points of

. Let

with

. Then there is some

such that

. It follows that the functions

and

differ at the point

. This completes the proof for the bullet 1 of Theorem 2.

To prove the bullet point 2, suppose that the family separates the points from closed subsets of

. It suffices to show that the evaluation map

is an open map. Let

be a non-empty open set. We show that

is open in image

. Let

where

. Since

separates the points from closed subsets of

, there exists an

such that

. Let

. Consider the following open set.

Clearly . We show that

. Choose

. Then

for some

. It is also the case that

. Thus

. This means that

and that

. This completes the proof for the bullet 2 of Theorem 2.

____________________________________________________________________

Embedding every space into a function space

In defining the evaluation map, we start with a space . Then take a family of continuous maps

. As long as the family of functions

separates points from closed sets, we know for sure that the evaluation map is a homeomorphism from

into a subspace of

. We now look at some choices for

. One is that

. Then we have the following corollary.

Corollary 3a

Any space is homeomorphic to a subspace of the function space

.

Because is a completely regular space, the family

clearly separates points from closed sets. Thus Corollary 3a is valid. In fact, the complete regularity of

only requires that we use

, the set of all continuous functions from

into

where

. We have the following corollary.

Corollary 3b

Any space is homeomorphic to a subspace of the function space

.

We can also let , the set of all bounded real-valued continuous functions defined on

. It is clear that

separates points from closed sets. So we also have:

Corollary 3c

Any space is homeomorphic to a subspace of the function space

.

____________________________________________________________________

One application

We demonstrate one application of Corollary 3a. When is a separable metric space,

has a countable network (see this previous post). It is natural to ask whether every space with a countable network can be embedded in a

for some separable metric space

? The answer is yes. We have the following theorem. One direction of the theorem is Theorem III.1.13 in [1].

Theorem 4

Let be a space. Then the following conditions are equivalent.

- The space

has a countable network.

- The space

can be embedded in a

for some separable metric space

.

Proof of Theorem 4

The direction is clear. As shown here,

has a countable network whenever

has a countable base. Having a countable network carries over to subspaces. The direction

is the one that uses evaluation map.

Suppose that is a countable network for

. Then

has a countable network, e.g., the set of all

where

,

is any open interval with rational endpoints and

is the set of all

such that

.

Any space with a countable network is the continuous image of a separable metric space. Thus there exists a separable metric space such that

is the continuous image of

. Let

be a continuous surjection. Then

can be embedded into

. The embedding

is defined by

.

By Corollary 3a, is embedded into

. Then

is embedded into

.

____________________________________________________________________

More on the evaluation map

In this section, we consider some special cases. As shown in Theorem 2, what makes the evaluation map a one-to-one map is that the family separates points of

(for short, the family is point separating). What makes the evaluation map a homeomorphism is that the family

separates points from closed subsets of

. In this section, we present one property that implies the property of separating points from closed sets. It is clear that if

is dense in

, then

separates points of

. In general, the fact that

is point separating does not mean it separates point from closed sets. We show that whenever

is compact, the fact that

is dense in

does imply that

separates points from closed sets.

The family is said to be a generating set of functions if it determines the topology of

, i.e., the following set is a base for the topology of

.

Since is assumed to be a completely regular space, we observe that if

is a base for

, then the family

separates points from closed subsets of

. The following theorem captures the observations we make.

Theorem 5

Let be a space. Let

. Then if

is a generating set of functions, then

separates points from closed subsets of

, hence the evaluation map

as defined above is a homeomorphism.

We now show that if is compact and if

is dense in

, then

separates points from closed subsets of

, making the evaluation map a homeomorphism.

First one definition. Let be a space. For any finite

consisting of functions in

, define the maximum of

to be the function

such that for each

,

is the maximum of the real values in

. In other words, the maximum of

is the pointwise maximum of the functions in

. It is not too difficult to show that the pointwise maximum of finitely many continuous real-valued functions is also continuous. We have the following lemma and corollary.

Lemma 6

Let the space be compact. Suppose the family

is dense in

such that the pointwise maximum of any finite set of functions in

is also in

. Then

separates points from closed subsets of

.

Proof of Lemma 6

Let and let

be a closed subset of

such that

. For each

, consider the open set:

where is the open interval

and

is the open interval

. For each

, choose

. The set of all

is an open cover of the compact set

. Choose

such that

cover

where each

. Let

be the pointwise maximum of

. By assumption,

. It is clear that for all

,

. Thus

.

Let . It is also clear that

for all

, implying

. Thus

. Thus completes the proof that

separates points from closed subsets of

.

Corollary 7

Let the space be compact. If

is a dense subspace of

, then the evaluation map

as defined above is a one-to-one map.

In Corollary 7, even if is not closed under taking pointwise maximum of finitely many functions, then throw all pointwise maxima of all finite subsets of

into

and then apply Lemma 6. Throwing in all pointwise maxima will not increase the cardinality of

. For example, suppose that

is compact,

is separable and

is a countable dense subspace of

. Even if

does not contain all the pointwise maxima of finite subspaces, we can then throw in all pointwise maxima and the subspace

is still countable. Then the compact space

is homeomorphic to a subspace of

. Since

,

is separable and metrizable. Thus the compact space

is separable and metrizable. The following corollary captures this observation.

Corollary 8

If is a compact space and the function space

is separable, then

is metrizable.

____________________________________________________________________

Reference

- Arkhangelskii, A. V., Topological Function Spaces, Mathematics and Its Applications Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1992.

____________________________________________________________________